First Peoples also have collective rights

By Daniel Wilson

By Daniel Wilson

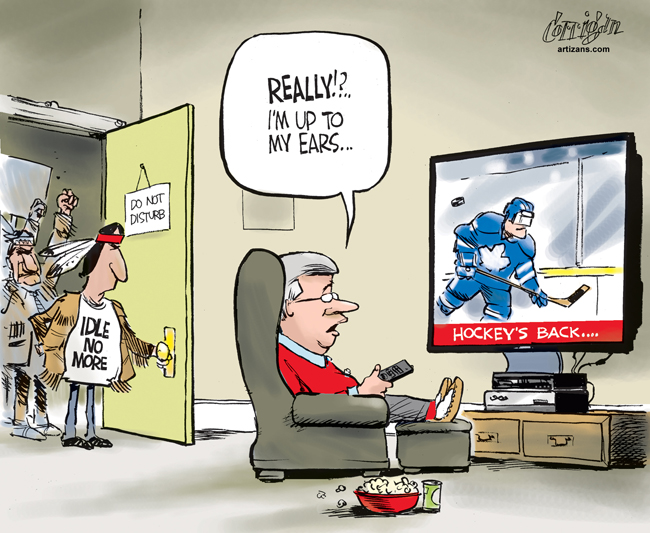

Working in defence of Indigenous rights, I have heard the rebuttal far too often that Indigenous people “fail to take personal responsibility” for their circumstances.

Putting aside the inherent racism, the broader implications lie in the confusion between individual and collective rights.

Canadians are familiar with individual rights. Those are the values American TV shows tell us are the foundation of modern society. We have freedom of expression, religion, association and assembly. We have civil and legal rights such as voting and due process. “Every individual” has equal rights according to Section 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution Act, 1982.

Enthusiasm for even these rights has limits. Free assembly can inconvenience commuters. Due process means that some people who are guilty according to the local radio talk show don’t go to jail once a court has heard the facts. But for many, it is collective rights that are the real problem.

One collective right appears in the second part of Section 15 of the Charter, allowing for affirmative action to ameliorate disadvantage. This is what many people think is the extent of Indigenous rights — “reverse discrimination” — standing in opposition to the fundamental value of individual equality.

While Indigenous citizens do have the same rights to equality as other Canadians, Indigenous rights are a different matter altogether.

Indigenous rights appear in Section 25 of the Charter, where it says that none of the other rights and freedoms guaranteed to Canadians diminish the rights that pertain to the “aboriginal peoples of Canada.” This includes equality rights.

Indigenous rights existed before Canada’s Constitution, and in Section 35 of that document, they are “recognized and affirmed.” Further, “In this Act, ‘aboriginal peoples of Canada’ includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.”

Note the use of the word “peoples” rather than “people.” The difference is only one letter. Yet that letter makes the difference between rights held by individuals and those held by a collective, by nations.

That is why we should be careful with language.

The most common confusion is around hunting and fishing rights. Those rights are manifest by individuals, as it is people who do the actual hunting and fishing. But the rights belong to the Indigenous nation.

Complaints that the same rules do not apply to an Indigenous hunter as to others miss this essential point. As individuals, they hold exactly the same — equal — rights. Those rights are whatever is determined by their nations, which are different.

Provinces regulate hunting because that is how Canada, in its collective wisdom, decided to arrange things. Indigenous nations set the rules for their members because they have done so since before Canada existed and still hold every legal right to do so. Just as provincial rules may vary, some Indigenous governments will choose more restrictive rules that respect biodiversity and some may not.

It isn’t only those who stand against collective rights who make this mistake. Some supporters of grassroots empowerment — no doubt a good thing — seem to think that Indigenous rights belong to individuals as well.

For example, the Government of Canada has a duty to consult Indigenous peoples on actions that affect their rights. It owes no such duty to individuals. The fact that Canada consistently fails to carry out its duties to Indigenous nations doesn’t help matters. People want to protect these rights, but as things stand, the citizens of an Indigenous nation are unable to hold either Canada or Indigenous governments to account.

The responsibility of an Indigenous nation should be to its people. But Canada makes Indigenous governments accountable to the bureaucracy in Ottawa rather than their citizens.

If Canadians truly want Indigenous people to take personal responsibility, they must dismantle the colonialist structure that treats Indigenous governments as mere administrative agencies of Canada.

Empower Indigenous people to exercise their individual rights as citizens by allowing Indigenous peoples to exercise their collective rights as nations.

Daniel Wilson served 10 years as a diplomat in Canada’s Foreign Service, before working for the Assembly of First Nations as Senior Director of Strategic Policy and Planning. He is of Mi’Kmaq-Irish heritage.