Indian ‘performers’ not just stereotypes

Linda Scarangella McNenly examines Native performers’ involvement in both the original Wild West shows, undertaken by the likes of Buffalo Bill Cody, and the modern productions by Disney in France.

Despite the chronological distance of more than a century between the original and modern shows, McNenly convincingly shows how Native motivations and actions remain remarkably similar. Her basic premise is that these shows, while part of the colonial relationship, serve as a point of cultural interaction referred to as a “contact zone” where cultures are transformed through the “process of negotiation and incorporation” (192).

She also argues that the concept of “agency” involves more than resistance. Native participants in the Wild West shows were there for a variety of reasons – money, travel, adventure, and escape from poverty on the reserve and Indian agent control. Performers often traveled and worked with their families while in the show. McNenly illustrates that despite the spectacle of the shows and the creation of the stereotypical Indian, Native performers were glad to be performing dances and ceremonies both on and off stage that were illegal in Canada or the United States.

McNenly also shows how performers’ costumes were at the same time stereotypical and unique – for instance many incorporated beadwork from the performers’ communities alongside the feathered bonnets.

Overall, an admirable study of how Wild West shows were more than stereotypical spectacles for Native performers.

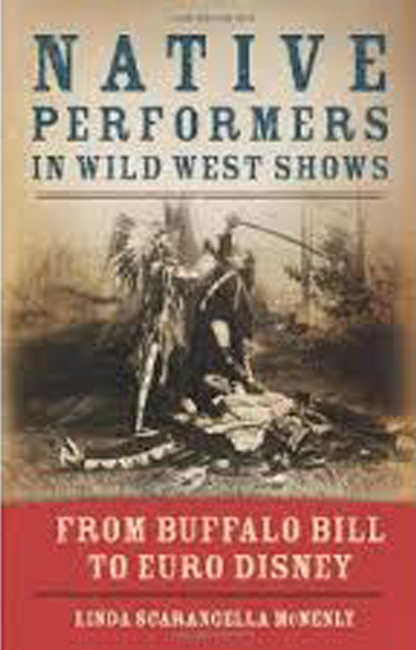

Linda Scarangella McNenly, Native Performers in Wild West Shows: From Buffalo Bill to Euro Disney. Norman University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Lynda Mannik explores the views of the organizing body of the Royal Easter Show, the Canadian government and Indian Affairs, the eight First Nations men taking part, the accompanying RCMP officer, and the view of the public in Australia.

The eight men’s Australian adventure – including “Joe Crowfoot and Joe Bear Robe from the Blackfoot Reserve, Frank Many Fingers and Joe Young Pine from the Blood Reserve, Edward One Spot and Jim Starlight from the Sarcee Reserve, and Johnny Left Hand and Douglas Kootenay from the Stoney Reserve” (53) – illustrates the complex links between colonialism, performance, and agency. For the First Nations men and their descendants the chance to participate was important and a source of pride. Despite being under the watchful eye of an RCMP officer, it offered participants a chance to travel, display their rodeo skills, and experience life outside of the Indian Act.

Mannik’s work in a very straightforward manner documents “the reordering of stereotypes and the renegotiation of cultural/colonial boundaries by tracing the movements of individual people presenting distinct views of national identity.” Which aims by examining “multiple perspectives [that] it is possible to see how cultural meanings are interwined, and how new meanings take form.”

Her work “emphasizes the impact individuals can have in alterations to ideological meanings based on national identity, particularly when a foreign audience’s interpretation is taken into account.” (137).

Lynda Mannik, Canadian Indian Cowboys in Australia: Representation, Rodeo and the RCMP at the Royal Easter Show, 1939. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2006.