Macdonald, Mowat scorned treaty ‘chains’

By Dr. David Shanahan

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the Treaty of Niagara, one of the most important agreements in Canadian history, and one that most Canadians know nothing about.

In fact, the many treaties that have been made between the Crown and First Nations are generally ignored, not just by the general public, but by most levels of government too. No matter how much First Nations try to remind the governments, federal and provincial, of the sacred and lasting nature of these solemn treaties, history shows that the Crown has neglected them and, as a result, indigenous people have lost rights, benefits and civil rights over those 250 years.

The really ironic thing about this is that both levels of government have used native arguments regarding treaties for their own advantage at times, possibly not even realizing they were doing so. First Nations have always insisted that treaties are agreements between nations, freely entered into by sovereign peoples. They have described these agreements as golden or silver chains, binding both parties together in friendship, which both sides have to nourish, so that the links remain shining and strong.

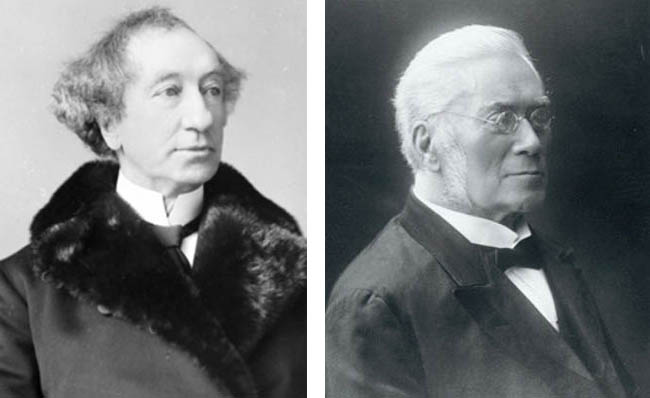

Both of these ideas were used by some of those who caused most damage to indigenous peoples by rejecting those same ideas when it came to First Nations treaties. After Confederation, which involved, I believe, a renegotiation of many treaties without consulting the First Nations, the federal and provincial governments began to compete to see which would have jurisdiction over lands and resources. Sir John A. Macdonald brought many of these conflicts to the Privy Council in London, for legal decisions on those issues. Oliver Mowat, Premier of Ontario, was his main rival. The two men did not like or respect each other very much.

In 1875, when the Liberals were in power and Macdonald was in the Opposition in Ottawa, a young M.P. called Aemelius Irving introduced an amendment to an Act setting up the Supreme Court of Canada. He wanted to make it the final court of appeal for Canadians, instead of the Privy Council in London. Macdonald opposed Irving’s motion, claiming that such a move would damage relations between the Dominion and the Empire, a relationship which he described as “a golden chain, and he, for one, was glad to wear the fetters.” This was the man who hanged Louis Riel, whose neglect of his responsibilities as Minister responsible for Indian Affairs provoked rebellion, and whose Indian Acts imposed intolerable burdens on First Nations across the country. He had no love for the golden chain that was supposed to tie him under treaty to the native people of Canada.

Oliver Mowat was, perhaps, even worse. He won many victories over Macdonald at the Privy Council, where one of his main spokesmen was Aemelius Irving, the man who had tried to remove the same Privy Council from the Canadian legal system. Mowat’s argument in each case was that Confederation was a series of treaties between the provinces, and treaties could not be changed without the consent of all parties to them. Yet this man passed laws denying First Nations people their treaty right to hunt and trap and fish. His officers arrested and harassed Anishinabek men and women, confiscated their traps and boats, and sent them to jail for exercising their treaty rights. Their chains were neither golden nor silver. The Ontario Government continues this tradition today.

It seems that the sacredness of treaties and the solemn bond of the Treaty Chain was only applicable to governments. When it came to real treaties, there was nothing sacred about government attitudes.

History can be very ironic, can’t it?

Dr. David Shanahan has worked on First Nations treaty and land claim issues for the past 25 years.