Canada’s interim Comprehensive Land Claims Policy is no more than colonial policy

By Lynn Gehl PhD, Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe

By Lynn Gehl PhD, Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe

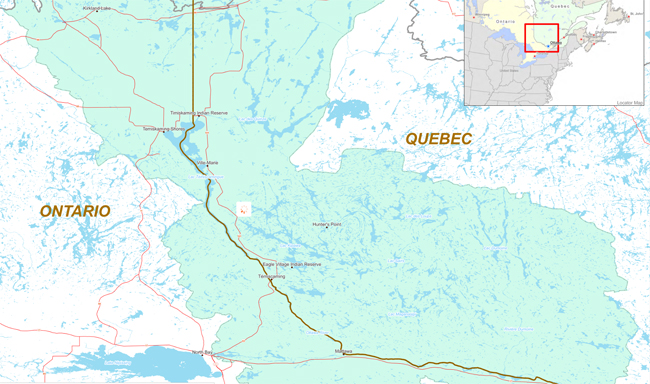

ALGONQUIN TERRITORY – Chief Harry St. Dennis, Chief Terrence McBride, Chief Madeleine Paul, and Chief Casey Ratt all argue “the status quo is not tenable”. The interim comprehensive land claims policy recently put forward by Canada as a response to the recent Tsilhqot’in Supreme Court of Canada decision is a perpetuation of colonial policy. Policy must meet law.

Canada’s long standing Comprehensive Land Claims Policy requires Indigenous Nations to extinguish their rights in exchange for small amounts of land and one time buy-outs. This amounts to genocide as defined by Raphael Lemkin and the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

While the knowledge relevant to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) decision which recognized Tsilhqot’in rights and title is circulating, it seems that people need help with establishing their relationship to the knowledge. In the work I do regarding Canada’s land claims and self-government policies as they relate to the Algonquin Anishinaabeg in Ontario, many people contact me asking me if this decision means anything. When responding I always begin with qualifying that I am not a lawyer nor am I a political scientist. Then I offer this explanation: there is theory, in this case legal theory, and then there is practice. It really is this simple: theory minus practice equals rhetoric.

With that said, here I offer this summary of several resources as a way to help people find their way through the complexity of the matter.

First, Canada has a long history of favourable SCC decisions regarding Aboriginal rights. Regardless, these decisions have not manifested into anything substantial for Indigenous people. These SCC decisions include the 1985 Simon case which determined that all treaties remain valid even if they predate the invention of Canada, and also that the burden of proof be reasonable versus imposing the need for genealogical records; the 1990 Sparrow case which determined that Indigenous rights cannot be extinguished, are not frozen in time, and have priority over all else; the 1996 Van der Peet case which determined that Aboriginal rights must be liberally defined, and when doubt exists they must be interpreted in the Aboriginal favour; and the 2003 Powley case which determined that the purpose of section 35 of the Constitution is to protect Aboriginal culture for future generations. Indigenous lawyer/political science professor Dr. Pam Palmater offers a publicly available lecture of this judicial history and what she calls the “empty shell of section 35”. Click here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f3tBeoeundQ

Second, the Tsilhoqot’in SCC decision was rendered on June 26th, 2014. The CBC conducted an interview with Palmater that same day where she argued the Tsilhoqot’in decision is extremely significant as it determined that Aboriginal rights are exclusive to all other rights where provincial and federal laws such as the Forestry Act do not trump them. This decision, she points out, clarified that consent, versus mere consultation, is a requirement. It also clarified the right of Indigenous people to protect the communal nature of their land and water for all future generations, Canadians included. What is more, Palmater stated that the decision clarified that Indigenous people are entitled to their share of the economic benefits from their land and resources. Click here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YepdCf2qFc4

Third, in September 2014, shortly after the SCC decision, Canada put forward their interim comprehensive land claims policy in an effort to reconcile law with policy. The history of the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy and its evolution, or better said lack thereof, has been a controversial matter in its requirement that Indigenous Nations extinguish their rights; as such, Indigenous people and leaders were eager to read it and offer their analyses. Click here to read this new policy initiative:

Fourth, the Union of British Columbia Chiefs retained Bruce McIvor for his legal analysis of the interim comprehensive land claims policy. In November 2014 McIvor offered his synopsis of the four main issues that remain problematic for Indigenous Nations: First, it “disregards the need for high-level discussions between Canada and First Nations leadership to reframe the approach to achieving reconciliation on Aboriginal title and rights claims”; Second, it “fails to acknowledge that recognition of Aboriginal title must be the starting point for all negotiations and agreements between Indigenous peoples and the Crown”; Third, it “fails to address the need for the Crown to seek and obtain the consent of Indigenous peoples before making decisions that will affect Aboriginal title lands”; And fourth, it “fails to consider and adhere to the underlying principles of Aboriginal title”; and it “imposes a unilateral approach which is inconsistent with Canada’s fiduciary relationship to Indigenous peoples and its obligations to act in good faith in negotiations concerning Aboriginal title and rights”. The short story is that the policy does not meet new law. Click here to read this analysis in full:

Fifth, policy analyst Russell Diabo and scholar Dr. Shiri Pasternak offer their joint analysis of the interim comprehensive land claims policy. In line with McIvor they argue, “the objective of Aboriginal Affairs’ recent announcement on the land claims policy was not to reconcile the policy with the Supreme Court’s findings on Aboriginal title, but to accelerate the policy framework of Aboriginal title extinguishment, particularly in the areas of major resource development projects like the proposed pipelines in British Columbia.” Continuing, they add, the “federal government is fighting tooth and nail against ceding an inch of legal authority over land despite the pronouncement from the highest court in the land.” Their full discussion can be gained from this link:

Sixth, it is the view of Algonquin Chiefs of Quebec – Harry St. Dennis, Terence McBride, Madeleine Paul, and Casey Ratt – that, “the disconnect between federal policy and practise on the one hand, and the law on the other, has become even more glaring. In particular, while the courts have acknowledged the need for policy and process that covers the spectrum from asserted rights through to final negotiated agreements, including the need to consult and accommodate in the interim, federal policy has failed to provide practical measures to address these realities.” In this way, Algonquin Chiefs argue this new policy reform reflects the same failed policy approach.

These same Algonquin Chiefs offer specific elements of the policy that they are particularly dissatisfied with: On the matter of certainty, Canada’s continued emphasis on extinguishment is not acceptable. On the matter of loan funding, it remains that Canada will only enter into negotiations on the basis of loans which provides an unfair advantage because negotiations drag on to the point that First Nations become mired in debt. On the matter of compensation, Canada’s policy continues to avoid this issue altogether. It is in these ways and more that St. Dennis, McBride, Paul, and Ratt argue “the status quo is not tenable”. To read more:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/245461195/First-Nations-Strategic-Bulletin-August-Oct-14

Lynn Gehl, PhD is an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe. She has a section 15 Charter challenge regarding the continued sex discrimination in The Indian Act, is an outspoken critic of the Ontario Algonquin land claims and self-government process, and has three books titled Anishinaabeg Stories: Featuring Petroglyphs, Petrographs, and Wampum Belts, The Truth that Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process, and Mkadengwe: Sharing Canada’s Colonial Process through Black Face Methodology. You can reach her at lynngehl@gmail.com.