Coming full circle: 20 years since the Ipperwash Crisis

By Monica Virtue

For many Canadians, the 20th anniversary of the “Ipperwash Crisis” may be the first time they hear the name Dudley George. For others, September 6, 2015, will be a day of solemn reflection – a painful reminder about how government, police and the media can get a story wrong.

When Anthony “Dudley” George was killed by an Ontario Provincial Police sniper on September 6, 1995, I was entering my final year of high school. Five generations of my family had vacationed at Ipperwash Beach, so it wasn’t a surprise when the confrontation between First Nations protesters and a police riot squad hit the front page of the newspaper. Members of the Chippewas of Kettle & Stony Point First Nation had already been camped out in tents and trailers on the grenade ranges of Camp Ipperwash over the federal government’s failure to return the land, appropriated in 1942 for a WWII training facility. Eventually, resentment escalated into protesters occupying the adjoining Ipperwash Provincial Park. Nobody could have predicted that within three days, Dudley would be dead, the protesters accused of having guns, and Ontario Premier Mike Harris accused of ordering the police raid to reclaim the province’s 108-acre tourist attraction.

By 2003, Dudley’s family was eight years into a legal battle with Harris and the OPP. As an emerging filmmaker, I planned to make a short documentary in the hopes it would join calls for a public inquiry into the shooting. After meeting Dudley’s brother Sam, the project grew more complex. Sam told me I could follow him with a camera, with one condition – that I wear my running shoes. He wasn’t kidding.

Sam’s civil lawsuit moved so fast I could barely keep up. He was patient as I trailed him, lugging my camera and asking basic questions that, in retrospect, must have been annoying. I would clip a wireless microphone to him and listen through headphones as he laughed and joked, always singing traditional drum songs. He wanted me to learn what everyday life on his First Nation was like – the good and the bad. The experience was outside my comfort zone – new foods like fry bread, a new language, and new ways of looking at the land. It forced me to slow down and listen, and was a jolting lesson about white privilege and the sheltered world I had been raised in.

During the Ipperwash Inquiry, I began working with his lawyers on a second film on the history of Ipperwash Park. We focused on characters involved in the Park’s creation – the Mayor of Sarnia, the Member of Parliament, the bank manager who issued the mortgage, and his brother, the Indian Agent. It appears Indian Act laws may have been broken to obtain the beachfront.

When Sam died of cancer in 2009, it felt like the stress of his 12-year battle for the truth had killed him. He put himself in the public eye to humanize Dudley, but once there was no longer a “smoking gun” involving Harris and Sam had passed away, the story fell out of the news cycle. There was hope the 100 recommendations made by Justice Linden would be implemented, but over the years there was a sinking feeling as various parties backed away from them.

Thankfully, I’ve collected a large volume of content that’s kept me committed to the story. I can put on headphones and listen to Inquiry exhibits, such as audio recordings from the OPP command post. I can hear officers discuss plans to “amass an army” 24-hours before Dudley’s death. The following 24-hours, as heard on the recordings, are a chilling reminder of why the 100 recommendations are so important.

At this moment, it seems a clear commitment to a full environmental clean up of Camp Ipperwash is a vital step my government must take for healing to begin. Meaningful reconciliation has become a key theme for me as I pursue my Masters in Digital Futures at OCAD University, using Ipperwash as my thesis project. I’d like others to experience Ipperwash the way I have – through headphones, with the beach and surrounding landscape the main character. With technologies like 360-degree audio and video, I’m hoping others will open their hearts to this powerful story, too.

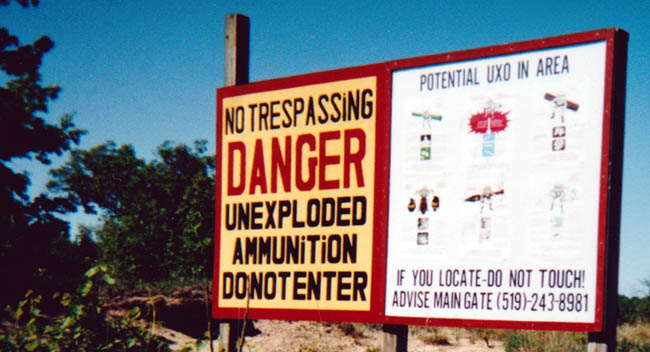

Photos: Same environmental damage, different signs. Ammunition warning sign is posted along the fence line of the Stony Point First Nation (the former Camp Ipperwash) in 2003 (left) and in 2015 (right).