Book review: World of Anishinaabe through an understanding of artistic expression

By Karl Hele

By Karl Hele

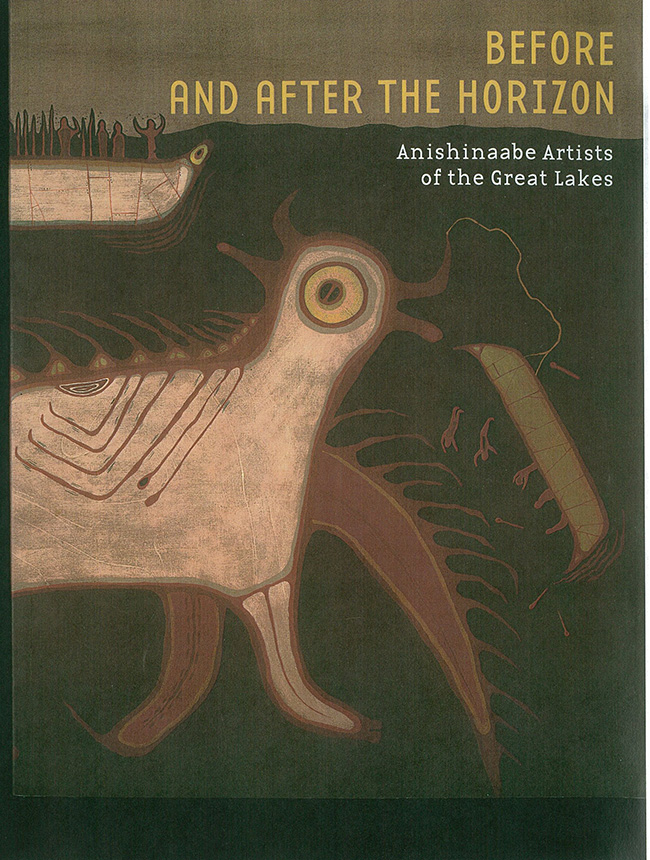

Emerging from an Anishinaabe artists’ exhibition of the same name, Before and After the Horizon, seeks to illustrate through art and words a sampling of how the ‘people’ have viewed the land and water of the Great Lakes. The book is lavishly illustrated with images from museums and art gallery collections dating from the 1600s to the modern era. These artistic works, are then examined and described by contributing authors to offer the reader an entry point to beginning to understand, interpret, and explore the epistemological world of the Anishinaabe. Simply, Before and After the Horizon seeks to explore and represent how historical and contemporary artists have viewed the Great Lakes landscape as a “place where earth, sky, and water come together in the Great Lakes landscape, but also the border between what is perceived and what remains hidden, the known and the unknown” with the border naturally shifting though time and from observer to observer (7).

Before and After the Horizon offers an introduction that sets the tone for the volume, highlighting the history of contact and cultural development drawing from our experiences over the centuries. For the uninitiated, and for the purpose of the book, the term Anishinaabe is defined as encompassing the Ojibwa, Chippewa, Ottawa, Odawa, Algonquin, and Potawatomi peoples, noting that these designations are the result of labels applied by various colonizers on groups of people who identified by dodem and/or geographic location. This definition is then utilized throughout the book to link art and artistic styles and expression through time and space. The entire volume explains to the viewer and reader how “Anishinaabe stories, histories, and experiences of relations to the Great Lakes as a material and conceptual place can be perceived in some measure in the things made by Anishinaabe artists” (15). Alan Corbiere and Crystal Migwans in “Animikii miinwa Mishibizhiw” examine how artists in the past utilized the concept of animikiig and mishibizhiig to illustrate the asymeterical multi-alities of cultural expression to represent our complex view of the cosmos. Ruth B. Philips’ chapter “Things Anishinaabeg” offers a limited exploration of “four visual strategies” utilized by artists to represent a distinctive intellectual and cultural tradition (53). Her four visual strategies are [1] ornament, [2] space, [3] expressive ambiguity, and [4] animacy. Most interestingly, Philips notes that Anishinaabe artists were playing with visual illusions long before European artists (65). The final chapter by Gerald McMaster offers exploration of the artists’ work from the exhibition. It highlights modern works by Arthur Shilling, Norvel Morrisseau, George Morrison, Daphne Odjig, Carl Beam, Robert Houle, Ron Noganosh, Blake Debassige, and David P. Bradley, among others. Each artist is highlighted along with his or her intellectual, cultural, and experiential influences that led to their artistic endeavours. All of this is followed by a humourous extract from Shrouds of White Earth by Gerald Vizenor.

Overall this is an excellent book that has something to offer to both insiders and outsiders to the world of the Anishinaabe through an understanding of artistic expression.

David W. Penny and Gerald McMaster, eds. Before and After the Horizon: Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, 2013.