Anishinabe Kwe and The Great War

Submitted by Laurie Leclair

An estimated 4,000 status Indian soldiers, many of them members of the Anishinabek Nation, fought in the Great War. This statistic is all the more remarkable when we see that it represents an enlistment average of one in three First Nations’ men between the ages of 18 and 45. For example, at the start of the war, the Chippewas of Rama had a total male population of 57, from which 37 men enlisted. The Mississaugas of Alnwick sent 31 of its 64 eligible men. Eleven men from Georgina and Beausoleil Island from a total of 23 joined. Totals did not include Métis, Inuit, non-status individuals, or the Indigenous populations in Newfoundland that were also strongly represented overseas. Despite an increasing awareness of the war’s huge toll on its soldiers and the fact that status Indians were exempt from service since 1918, recruitment among First Nations men actually rose as the war progressed, leaving behind communities that were very much diminished.

These numbers certainly speak to the men’s bravery, but they also lead to the natural conclusion that Indigenous women were in some cases almost exclusively shouldering the responsibilities of life back home, from raising and feeding their children and other dependants, to working their farms and maintaining jobs off-reserve. All of which would be secondary to the emotional strain of having their loved ones so far away and in such danger. In fairness, Canadian women in general shared this experience, but given the disproportionate number of Indigenous men who enlisted, Indigenous women must have experienced war time stress most keenly.

While they coped with life’s daily challenges, Anishinabe kwe also proved themselves to be generous with their time. Many reserves participated in patriotic leagues and charities. They collected clothes and food to send overseas, organized box socials and fund raisers, held card parties and bazaars. Also, in an effort unique to First Nations’ women, several groups found they could raise a lot of money by selling baskets and beadwork.

Each community preferred its own charitable organization. For example, members of the Audeck Omni Kaning First Nation raised money through Maple Taffy Socials and school drives, Rama women donated to the Orillia Patriotic Fund, the women of Wasauksing First Nation worked for the 23rd Regiment Overseas contingent, and Garden River women volunteered for the Algoma War Chest Fund. These efforts were over and above the large amount of money that each First Nation selflessly donated from its trust fund, which collectively amounted to over $45,000 by war’s end.

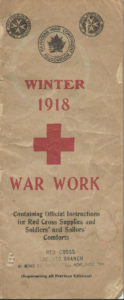

Indigenous women throughout Canada were involved in several of the larger international organizations; however, the majority of Indigenous women’s groups in Ontario worked within the parameters of the Red Cross Society, perhaps because of the Canadian Civil Service’s strong connection to it. The Department of Indian Affairs, a branch of the Department of the Interior probably presented The Red Cross as an option for volunteering and sent this message to reserves through its Indian Agents. It was also an easily accessible charity. A district listing published in a Red Cross pamphlet from 1918 recorded stations in Owen Sound, Cobourg, Windsor, Peterborough, and Fort William, areas that would have handled parcels created by Anishinabe kwe.

A review of this same pamphlet helps us appreciate the type of volunteer work that women did during these war years. Charitable acts assumed two forms. The first category focused on the role of the society itself, which included raising money to buy ambulances, to build and equip hospitals, to purchase medical supplies and drugs, to knit socks and make bandages. Money and goods shipped over for this portion went to the sick, wounded and prisoners of war. The Red Cross also ran a second program sponsored by the Canadian War Contingent Association known as “Soldier’s Comforts”. Here, sewing, knitting, foodstuffs and cigarettes were boxed up and sent to men in the camps and in the trenches. Judging by the Annual Reports of Indian Department, the majority of Anishinabe kwe’s efforts went towards this latter program.

In providing boxes of “Soldier’s Comforts”, women were encouraged to make caps, small toiletry bags, sewing kits known as “housewives”, towels, bandages and slings. They were also asked to knit, and Anishinabe women excelled in knitting.

Socks were the most requested item. These included regular socks and socks to cover amputations, both a large style that fit the thigh and a smaller version which cosseted the ankle or arm. In an effort to standardize the garments arriving from home, the Red Cross provided knitting patterns, dictated wool selection and preparation. For example, “to avoid blood-poisoning from dyes” the pamphlet instructed, “wash wool thoroughly in boiling water and rinse in several waters before knitting”. Those who were skilled at knitting were asked to concentrate their efforts on making socks and to let the eager amateurs work on easier patterns like mufflers, wristlets and caps. Completed socks were lightly sewn together in pairs and then bundled by the half dozen. Women also collected money so that their soldiers could buy luxuries like hard candy and chocolates, tins of fruit, cakes, tobacco, matches, lighters, stationary and toilet paper.

Once the soldiers’ comfort boxes were assembled, a small list was enclosed bearing the names of the women or the charitable group that had prepared the box. Next, the package went to the Canadian Red Cross Warehouse on King Street East, Toronto, before it was shipped overseas.

It has been estimated that over 300 First Nations men died during the war. These statistics do not take in the number of men who succumbed afterwards from their injuries or due to the respiratory diseases that followed them home. Some veterans also suffered from what has only recently been recognized as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). After November 1918, although the Great War had ended, many Indigenous women also had to assume the role of caregiver alongside the several jobs that had been placed upon them since 1914.

In 1919 The Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, wrote:

The fine record of the Indians in the great war appears in a peculiarly favourable light when it is remembered that their services were absolutely voluntary, as they were specially exempted from the operation of the Military Service Act, and that they were prepared to give their lives for their country without compulsion or even the fear of compulsion…It is therefore, a remarkable fact that the percentage of enlistments among the Indians is fully equal to that among other sections of the community and indeed far above the average in a number of instances. As an inevitable result of the large enlistment among them and of their share in the thick of the fighting, the casualties among them were very heavy, and the Indians…must mourn the loss of many of their most promising young men. The Indians are especially susceptible to tuberculosis and many of their soldiers who escaped the shells and bullets of the enemy succumbed to this dreaded disease upon their return to Canada as a result of the hardships to which they were exposed at the front….

[From Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs (1919), p. 14]

Nearly one-third of aboriginal men aged 18 to 45 enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces during the Great War. The following is a table of enlistments for Ontario’s Anishinabe as recorded by the Indian Department at the close of the war and as these communities were known at the time:

| Community | Men Enlisted | Total Adult Male Population |

| Rice Lake | 43 | 82 |

| Chippewas of Nawash | “Not a single man of the class called remained at home” | |

| Alderville | 31 | 64 |

| Parry Sound | 20 | |

| Manitoulin Island and North Shore Lake Huron | 50 | |

| Moravians of the Thames | 42 | 79 |

| Chippewas of Saugeen | 48 | 110 |

| Georgina and Beausoleil Island | 11 | 23 |

| Chippewas of the Thames | 25 | 110 |

| Chippewas and Pottawatomies of Walpole Island | 71 | 210 |

| Sturgeon Falls | 35 | 103 |

| Chapleau Region | 40 | 101 |

| Mississaugas of the Credit | 32 | 86 |

| Munsee of the Thames | 11 | 38 |

| Scugog Island | 8 | 30 |

| Algonquins of Golden Lake | 29 | 32 |

| Chippewas of Rama | 37 | 57 |

Statistics from the Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs for 1919, p. 16.