Canada: ‘Conceived under the influence of alcohol!’

By Maurice Switzer

By Maurice Switzer

My Anishinabek Nation flag that flutters in the prevailing west winds off Lake Nipissing needs to be replaced twice a year.

A dark red banner bearing the image of a white Thunderbird gets whipped about pretty briskly, and it only takes a couple of months for the first fringes to emerge on its trailing edge.

That flag is important to me because it represents the long journey on which Indigenous peoples are travelling to restore the nation-to-nation relationship we once enjoyed with newcomers to our lands. Were it not for that relationship, Canada might not exist. Historians agree that 10,000 Indian warriors were all that stood between Canadian sovereignty and a much larger force of American invaders in the War of 1812.

My home is built on land that was once called the northern hunting grounds by families from my grandfather’s community that was once called the Alnwick Reserve but is now known as Alderville First Nation, located just east of Cobourg. They are part of the Mississauga nation whose members have dominated the Canadian shore of Lake Ontario since driving the warring Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) back to the other side of the lake whence they came 400 years ago.

Alderville was one of seven First Nations coerced into thinking that the 1923 Williams Treaty would be to their benefit. Instead, they were denied harvesting rights on their traditional territories in exchange for paltry one-time payments, and crammed onto postage-stamp reserves. Under terms of the 1876 Indian Act, the chiefs and headmen were not allowed to hire lawyers to protect their legal rights, one reason the Williams Treaty has been the subject of Federal Court hearings and is currently being re-negotiated.

So as preparations continue for the big birthday bash being planned to celebrate Canada’s sesquicentennial, those Williams Treaty First Nations are seven more reasons I won’t be joining the party. Along with those listed in the first of four columns of this “Canada 150” series, I have so far offered 48 examples of why many Indigenous peoples are opting out.

Here are some more:

- Five names – Pakiniwatik, Musquakie, Assiginack, Shawundais, Oshawanoo– if you don’t know who they are – and most Canadians don’t — you are unaware of some of the greatest heroes in Canadian history. Their exploits in the War of 1812 were instrumental in repelling the American invasion. Despite the role of 10,000 Indian warriors, the many casualties suffered by Native communities, and the pre-war promise Sir Isaac Brock had made of a huge North American Indian Territory in exchange for their support, Indigenous leaders were not even invited to attend the war-ending Treaty of Ghent ceremony on New Year’s Eve, 1814. As a result, Indians living south of the Great Lakes continued to be targets of American military aggression and political land grabs.

- When she died in 1829, Shanawdithit was the lone survivor of the Beothuk peoples, who had been hounded out of their traditional Nova Scotia homes by land-hungry settlers who wanted their rich fishing grounds for themselves. Starvation and European diseases spelled the end of this nation, a fate narrowly avoided by many Indigenous peoples across Canada as immigration exploded during the peace following the War of 1812. By 1838 there were only 1,425 Micmac in Nova Scotia, where 19,000 United Empire Loyalists had settled after the American Revolution. The province refused to pay for their education and health care, reasoning that they were doomed to disappear.

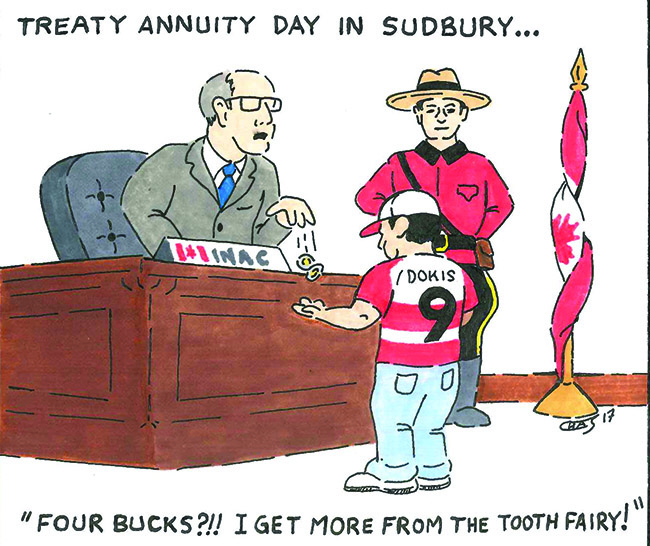

- Four dollars – that’s how much 25,000 “beneficiaries” of the 1850 Robinson Huron treaty each receive for agreeing to allow provincial and federal governments to share the use of the territories of 21 First Nations. Treaties began to be used as tools to deprive Indians of their lands as minerals began to be discovered in Northern Ontario. The Robinson Huron Treaty promised annuities that would reflect increases in wealth obtained from resources extracted from the territories. It is estimated that one mining company – Vale, formerly INCO – has extracted $1.5 trillion from its Sudbury operations in the past century. Vale miners – there are currently about 4,000 of them – each receive annual pay packages of about $130,000, more than all 25,000 First Nations treaty signatories, who have not had a raise since 1874.

- Confederation, the uniting of the provinces of Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island in 1867, was the political handiwork of 36 people – all men, all white. This is what all the fuss is about each July 1st, even though – for all intents and purposes, Canada was a British colony until the 1931 Statute of Westminster. There wasn’t even a Canadian Constitution until 1982. One historian, commenting on the hyperbolic consumption of spirits by the country’s first prime minister, Sir John A.. MacDonald, wrote: “Canada, like many a child, was conceived under the influence of alcohol!”

- In 1876 the MacDonald government presided over the implementation of The Indian Act, which introduced the concept of blood quantum as a social determinant in Canadian society. An Indian was defined as any male “of Indian blood”, or any woman married to an Indian. It is relevant that the prime minister routinely referred to Canada as an “Aryan” nation, thereby making him a political prototype for a later political leader known as Adolf Hitler. Other Indian Act provisions would outlaw traditional ceremonies and dancing, and require the wills of Indians dying on reserve to be probated by the federal Minister of Indian Affairs.

- In 1884 the Indian Act made attendance at government-sanctioned schools compulsory for Indian children. Over the next century 150,000 children would be forcibly removed from their families, many suffering horrific physical and sexual abuse at 130 of the institutions operated by Canadian churches. The odds of a student dying while attending residential school was one in 25, less than the survival rate for Canadian soldiers in World War II. In 1879, Sir John A. MacDonald explained the rationale for establishing the program: “When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”

- The largest “legal” mass execution in Canada took place on Sept. 25Th, 1885, when the government of Canada authorized the hanging of eight Cree warriors at Fort Battleford. In July of that year, Sir John A. MacDonald told the House of Commons: “…we have been pampering and coaxing the Indians. We must take a new course. We must vindicate the position of the white man. We must teach the Indians what law is. I personally knew General Custer, and admired the gallant soldier, the American hero.”

****

This is hardly reading material to put one in the party mood.

But that’s the point.

Indigenous peoples remain optimistic that there can be a better future for them in this place called Canada, which comes from a Huron word “Kanata” meaning village or settlement.

The first European to hear that word was likely French explorer Jacques Cartier who, when he visited the village that his Huron guides were referring to – Stadacona – repaid the inhabitants’ hospitality by – you remember – kidnapping the chiefs’ two sons!

Before there can be Reconciliation in the future, all Canadians need to know the truth about their past.

And that won’t have happened by July 1st.

Maurice Switzer is a citizen of the Mississaugas of Alderville First Nation. He lives in North Bay where he is the principal of Nimkii Communications, a public education practice with a focus on the Treaty Relationship that made possible the peaceful settlement of Canada.