Artistic projects honour Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women, Residential School Survivors

By Colin Graf

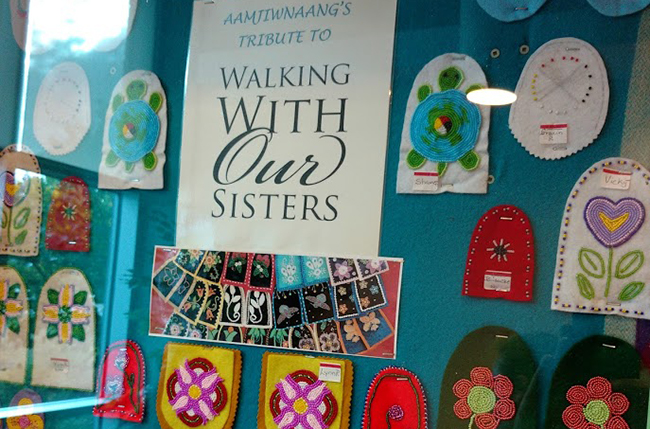

AAMJIWNAANG FIRST NATION – Residents have recently unveiled two artistic projects to remember and honour both Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and residential school survivors at their community centre near the southwestern Ontario city of Sarnia. Around 50 brightly-beaded moccasin tops, both adult and child-sized can now be seen in display cases on the walls of the Maawn Doosh Gumig centre in Aamjiwnaang, the product of seven months of work by both adults and children from the First Nation.

Titled “Walking With Our Sisters,” was inspired by, the travelling exhibit of moccasin vamps touring across Canada in remembrance of the MMIW. However, the Aamjiwnaang project has a different twist, in that smaller vamps were also beaded to honour children “who never returned” after being sent to residential schools, says Janet Steadman, Native Education worker at Sir John Moore school in Corunna, which many Aamjiwnaang children attend.

Chief Joanne Rogers told residents gathered for the opening of the display that it “helps to bring about justice and truth about what happened to our people and their families and helps increase awareness and prevention of the issues that surround First Nations in ending violence and abuse in our communities and against our people.”

The project started with Steadman’s efforts to educate all students at the school about the legacy of residential schools, and to teach the art of beading. When the whole community got involved, the idea of a permanent display was born. “It’s pretty overwhelming” to see the work finally finished, and to see what the children have learned, says Steadman, whose parents were both survivors. “Our kids know so much now about residential schools,” she says.

The moccasin vamps are not dedicated to individuals, but some local stories do stand out in her memory. Steadman says Aamjiwnaang’s former Chief Chris Plain told her of a local boy named Tommy Snow who died while at school, but his name “has disappeared”, with no known descendants. She beaded him a pair of mittens instead of the moccasin tops.

The second project is a memorial plaque with the names of Aamjiwnaang’s residential school survivors, organized and researched by Elder Geraldine Robertson, who was nominated for the Order of Ontario earlier this year by members of the United Church of Canada, for her travels across Canada speaking about her experiences.

With around 150 names, the memorial plaque has been two decades in the planning, Robertson says. She imagined a memorial in 1998 when she first asked Chief and Council to take steps to help the school survivors and their children, who were experiencing intergenerational trauma. Although a monument was built near the band office in 2002, “we just kept adding names” to the local list of survivors over the years, says Robertson. After church records were released through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, more names were added, dating back to 1874, she explains.

“It’s important to recognize the families that had to go through all the turmoil, and to realize how it (the residential school experience) impacted our community, and acknowledge that history for the future,” Robertson says. “This has had such a major impact on our people. It’s not something that can be forgotten,” she adds, explaining the purpose of the plaque.

Robertson pays tribute to others who helped her compile the list, including Diane Aiken, former member of Aamjiwnaang’s education committee, who helped find many names.