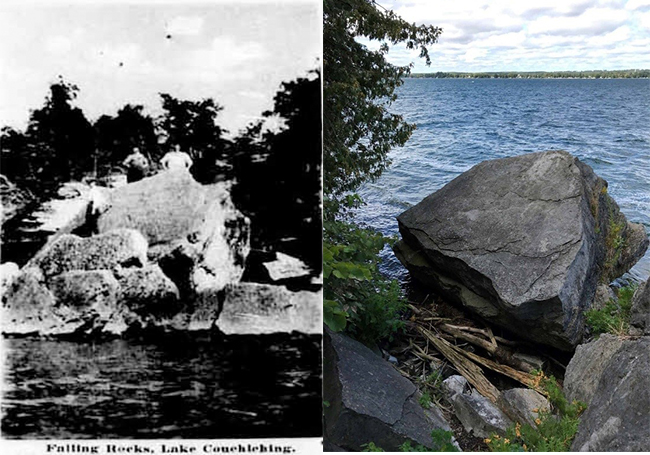

Fallen rocks at Geneva Park

By Ben Cousineau

The Sumerians (who lived in ancient Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq) were the first peoples to “write”. This occurred around 3000 BC. Needing to keep track of their grain and livestock but unable to rely on memory, the Sumerians “wrote” on damp clay tablets with a pointed tool. The damp clay eventually hardened, and the written materials were literally solidified in history.

While the Sumerians were the people who began the long process of the evolution of writing, they were not the first people to attempt to preserve information or tell a story in a visual way. Methods to do so have existed since time immemorial.

One of those methods was a pictograph (or pictogram). Different from a petroglyph, where pictures are carved into a rock, a pictograph is created by painting symbols and figures onto a rock. Using red or yellow ochre (a naturally occurring clay pigment), the illustrator would tell stories or preserve information by painting symbols and figures onto a rock.

Archaeological evidence supporting ochre used in pictographs dates as far back as 75,000 years ago. As ochre is a natural material, chances are much of its earlier evidence of use has eroded. First Nations people are one of many ancient cultures who used ochre to create pictographs. As a storytelling culture, we told stories verbally but sometimes through pictographs too.

On September 21, 1923, at the Council House in Rama, a series of interviews were being conducted by the federal government. Aiming to extinguish traditional hunting and harvesting rights through surrender, three Commissioners from the government of Canada were asking Rama men and women about where and when they hunted, how the territory was obtained, and how long the territory had been used for. About 25 Rama people were questioned. When Sampson George was interviewed, a fascinating piece of history emerged.

The interviewer, Mr. Sinclair begins to ask Sampson about the hunting limits.

Sinclair: Do you know the way these hunting limits were first acquired by the Chippewas? Did you ever hear anything about that?

George: Well, I hear a little about it. You know the Mohawks lived here in this country, and the Chippewas lived here too, and these two Nations they live sort of together all through the land but no particular Nation own it. They hunt together, and then they got a little trouble over this and over some marrying, and the other Nation starts to kill the Chippewas. Sometimes they go off to hunt and they never come back, and so the Chippewas took counsel what they will do, and they make big battles, and they won it and they defeat the Mohawks, and that is how we have these lands.

Sinclair: Then the Chippewas became the sole possessors of the land and drove the Mohawks off? This is the story of your tribe?

George: Yes, there is an inscription, no, a story on a rock here, where a Chippewa stands and the Mohawk is sitting down. That has been wrote over 300 years ago, and the Chippewa stand up and the Mohawk is down and it shows he has been beaten. That rock has been turned over now, but it is there and ti could be turned back, and that is convincing proof our Nation drove the Mohawks out of here. It is big, it is perhaps 50 ton. That’s the big Falling Rock at Geneva Point. I have seen it.

Sinclair: How long is it since the fell over?

George: Before the big war with the Germans. I’ll tell you we know that it is to happen, all these Indians who live here, because the old people of the many years ago – the old people who can see both ways – they tell us there is to be a great war, so big that it will be bigger than all the other wars put into one war, and they say that before the war comes, this rock will fall over, and we watch it, and then one day that rock fall upon itself, and then in one-two years this big great war, it comes to pass just like the old people who see both ways said in the long ago.

Sinclair: How was the inscription put on the rock? Was it carved?

George: No, it was painted, it was red paint – Indian paint, the picture was there.

Sinclair: How far is the rock from here?

George: About three miles over. It is on the shore of Couchiching, on this side. It is in what they call, “Geneva Park”.

The story about the Fallen Rocks is verified several more times, not just by Rama people, but also by people from places such as Scugog. Many stated they had seen the rock prior to its falling over, detailing what it looked like and what it meant. The painting on the rock was a story painted on stone to tell the tale of the Anishinaabeg defeating the Mohawk in war, and winning the territories where we still live today. It was painted in the 1600’s, and remained visible right up until the early 1900’s. Many generations saw the rock, and learned the history of their ancestors from the story that was painted on it.

The pictograph is hidden, probably submerged under water and never to be seen again. Today, the rock simply looks like a giant boulder. But now we know that it contains an important piece of history; it is a special place. It can be found at Geneva Park, by following the aptly named Fallen Rocks Trail.