Historian reminds us why many First Nations people fought in World War I

By Colin Graf

AAMJIWNAANG – The story of why at least 4,000 First Nations people fought in World War 1 for a country that would not grant them citizenship, would not let them vote, and would only let them leave reserves with permission from Indian Agents, is a complex one, but important in the history of First Nations in Canada.

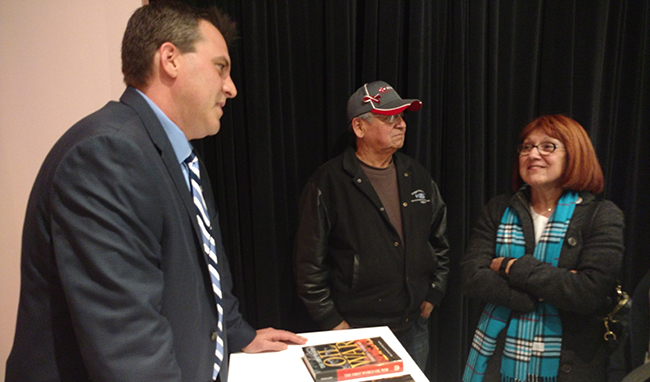

That was the message delivered to an audience in Sarnia, ON by historian Dr. Timothy Winegard recently. Traditional loyalties of First Nations people, the assimilationist and paternalistic attitude of the federal government, and a warrior legacy, were all powerful forces that shaped the participation of aboriginal peoples in the war, the audience at the Judith and Norman Alix Art Gallery heard.

When the Canadian government first started enlisting men in 1914, there was confusion in the government whether indigenous men could sign up or not, even though “tons of First Nations people” served in Canadian militia units before the war, Winegard said. When eventually the British War Office, which was in charge of Canadian soldiers at first, allowed aboriginal people from across the British Empire to enlist,they joined the lineups to go to France and fight. Some wanted regular employment, some joined to escape the restrictive pass laws that kept them living on reserves, and some were wanting to win warrior status within their communities, he explained. Many felt a strong allegiance, not to Canada as a country, but to the Crown, as many of their treaties had been signed with Queen Victoria before Confederation.

His research has show many indigenous soldiers felt equal rights in Canada would naturally flow from their participation in the war, Winegard claims. They felt “if we prove ourselves we will be worthy like everyone else,” he said. Some have doubted that was a common sentiment, Winegard says, but, he has “rooms full of records” to show these feelings were real at the time.

During the War, some First Nation soldiers experienced culture shock, as some had not even left reserves, let alone travelled overseas, according to Winegard, a former Sarnia resident born in Hamilton of mixed European and First Nations heritage.

Their culture was not completely suppressed, as Winegard showed a photo of one soldier wearing full regalia during a ceremony. We know quite a bit about their feelings, as their letters written in Indigenous languages were not censored as were the letters of most soldiers writing home in English or French, he told the audience. Some were offered alcohol for the first time, as it was not allowed on reserves, but many refused it, according to Winegard, a former Canadian Forces officer currently teaching at Colorado Mesa University.

At least one famous marksman, Francis Pegahmagabow, from Shawanaga First Nation became Chief Wasauksing after returning from the trenches. Pegahmagabow, the most decorated aboriginal soldier in the First World War, has been credited with 378 kills as a sniper, and has an exhibit in the Canadian War Museum. The legend of First Nation men as deadly snipers and fleet-footed, virtually undetectable scouts during the war is not fiction, Winegard said. It was not racism, but rather “military pragmatism” that put many of them into these roles, he said. For many, hunting and trapping provided their livelihood before the war, so they were well-experienced with tracking and shooting.

First Nations also raised money for the war effort. The “pretty unbelievable” sum of $45,000 was raised across the country, and was used to ”guilt other Canadians” into donating to the cause, according to Winegard, as in the famous poster of an invented blind chief.

While there were completely First Nation army units from other British Empire countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, that was not so with Canada, said Winegard. It was thought the higher susceptibility of First Nation people to tuberculosis could make it hard to keep numbers up in the unit, and the lack of English skills would make communication hard. Government officials also thought traditional animosities between some First Nations might also affect morale, and they were also concerned about the effect on indigenous communities back home if the unit were to be “wiped out”, as the Royal Newfoundland Regiment was during the war, Winegard explained. The Newfoundland unit lost 90% of its members in just 30 minutes of fighting at the battle of Beaumont-Hamel in 1916.

When young Canadian men were first conscripted into the army in 1917, indigenous men were included, in spite of treaty promises to the contrary. The government “quickly flip-flopped” on the decision, leading to confusion among First Nations soldiers who had enlisted voluntarily earlier in the War. Some took the wording of the decision to mean they can leave the army. Some who were in Canada before being sent overseas, left their units and were arrested and jailed for desertion. Private Moses Wolfe was shot in the shoulder on the Kettle Point lands in 1916 after soldiers came onto reserve lands looking for him. According to a complaint lodged with Indian Affairs from the chiefs at Kettle Point, Wolfe had come home “on account of sickness, lost his baby, and his wife was nearly died,” when the soldiers arrived, according to Winegard’s book “For King and Kanata”. He was later tried for desertion, jailed for a while, and returned to active duty.

At war’s end, most soldiers were given land grants, grants to start businesses, loans for farm equipment, and other forms of re-settlement help. First Nation soldiers “got none of that” and were just expected to “go back and be Indians on the reserves,” Winegard says. Francis Pegahmagabow, for instance, tried three times to get a government loan and was refused.

Learning about First Nations’ participation in World War 1 is important for today’s generations, said Aamjiwnaang First Nation Chief Joanne Rogers, attending Winegard’s presentation in Sarnia. “There are still many people (outside First Nations) who don’t know First Nations participated” in World Wars 1 and 2, she said in an interview. “We were there and we were part of that group that served the country.