Under 1850 Treaty all Crown revenues were to flow to Anishinabek

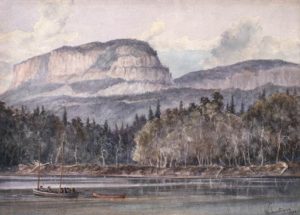

Bateau voyageur et canot chippewa, Thunder Bay, lac Supérieur. Photo from Government of Canada Library and Archives.

By Dorothee Schreiber

SUDBURY—Over the past 168 years, the Crown has neglected its obligations towards the Anishinabek under the Robinson Huron and Robinson Superior Treaties.

On June 22, the final day of hearings in the treaty annuities case, Harley Schachter, counsel for the Superior plaintiffs, argued that if the Crown is left to its own devices for another 168 years, it will continue on with business-as-usual, all the while claiming that its approach to treaty is reasonable and just.

The court is now in a position to promote reconciliation by laying out detailed principles of treaty interpretation, Mr. Schachter suggested. Whatever the parties might want out of the treaty relationship in 2018, treaty interpretation has to proceed based on rights and obligations actually agreed to in 1850.

The core of the Crown’s treaty promise was that all Crown revenues would be shared with the Anishinabek, Mr. Schachter said. One hundred percent of Crown revenues represents what Mr. Schachter called a “miniscule proportion of the wealth of the treaty territory; most of the wealth of the treaty territory has already been shared by the Anishinabek.” The Anishinabek allowed settlers to generate income on the discovery of any new sources of wealth. “The other portion of the wealth … was to be a flow-through of Crown wealth to the Anishinabek. That was the deal. That was the balancing.”

Over the past nine months, the court heard much evidence about the cross-cultural understandings held in 1850. When the treaty was made, Crown officials were clear on the fact that for the Anishinabek, relationship to the land included complete control over the land and its uses. It was only by virtue of a treaty that the newcomers could gain access to land and claim profits from activities on the land.

“That conception … is consistent with what Mr. Robinson admits to … in his official report,” Mr. Schachter told the court. “Absent the treaty he [Robinson] would have had to … pay the Indians the full amount of all moneys on hand and a promise of accounting to them for future sales.”

What the treaty did, therefore, was open up the land to settlers.

“Not to gain revenue for the Crown,” Mr. Schachter said. “But to allow the settlers to generate wealth on their own, without doing what Mr. Macdonell had to do with Shingwaukonse, enter into a contract directly with Shingwaukonse.”

If all Crown revenues under treaty were to flow to the Anishinabek, as was agreed to in 1850, the onus would be on the Anishinabek to consider the interests and goals of Canada and Ontario. Under such an arrangement, the responsibilities of the Anishinabek to consider the rights of other people would be the same as those already outlined for the Crown by the Supreme Court of Canada: “in good faith, and with the intention of substantially addressing” the other party’s concerns.

“The shoe is now on the other foot. We have the rights now … and if it was good enough for the Supreme Court of Canada to tell the Crown that you have to listen and consider the interests of other people, not withstanding your rights under treaty, we say … we accept the responsibility to fairly and honorably consider what the Crown’s interests, ambitions might be,” Mr. Schachter said.

“What is not right, Madam Justice,” Mr. Schachter said. “Is to deny us [Robinson-Superior plaintiffs] our rights entered into in 1850 because of a genuine … problem in 2018. We will deal with that problem by the process of reconciliation. But the court should not be worried that that’s going to fail now.” If the court were to make the finding that all Crown revenues flow to the Anishinabek under treaty, there would be plenty of opportunity for negotiation with the Crown before any money actually changes hands.

But unless the Crown honors its promise to share all Crown revenues, the Crown and the Anishinabek will find themselves back in court, Mr. Schachter suggested. This is because the Anishinabek made a reciprocal agreement under treaty.

Had the Crown promise to share the wealth of the territory been limited to the wealth derived from natural resources, then the only thing the Anishinabek would have given up is the right to raise revenues from natural resources.

“Is the Crown prepared to say to you [the court] that the Anishinabek retain the right to raise non-resource-based revenues on their own, from their own territory? … If the court were to rule that what the Anishinabek gave up was only resource revenues, then what we end up with is … another fight down the road about what’s left, and what hasn’t been given up. That doesn’t help reconciliation,” Mr. Schachter said.

Justice Hennessy asked Mr. Schachter what a flow-through model, in which all Crown revenues go to the Anishinabek, would mean for public services like schools and hospitals.

“Implicit in the question,” Mr. Schachter said. “Is the presumption that if the Anishinabek had received those taxes, the schools and the hospitals would not have been built? And that is not a fair assumption. I ask the court to remember that the treaty is truly a nation-to-nation agreement. It is a compact, it is part of our Confederation, it is part of nation-building. … And to presume that the use the Anishinabek nation state would make of the money would impoverish non-Aboriginals is a presumption that is not borne out by the evidence in this case. … If there is a presumption to be made … the evidence is that there would be an honorable fair sharing by the Anishinabek.”

“Essentially, is the answer, don’t assume what a self-governing Anishinabek nation would have done with taxes?” Justice Hennessy asked.

“I would put it a little bit further,” Mr. Schachter responded. “In an Anishinabek government, properly funded, it may very well be the case that the average non-Aboriginal person would be happier to live in such a society.”

Mr. Schachter ended his submission by reminding the court that “we are all treaty people.”

“There is a really important, fundamental value in Canada that we respect treaties,” Mr. Schachter said. “The road to a healthy Canada and one that benefits Canadians is respecting their obligations to the Anishinabek. … We all benefit when constitutional obligations are honoured.”