Chief’s Island grave story

By Laurie Leclair

On Thursday, November 8, 1923, a workman putting through a new sewer line across a property on St. Mary’s Street made the local news when he found bones mixed into the light grey earth. Closer investigation showed that they were human. As more skeletons were revealed soon after, their obvious antiquity and associated burial goods proved that these were the remains of people who had lived centuries before the coming of the Europeans.

Although the workman may have been shocked by his discovery, digging up skeletons was not an unusual activity for Orillia construction crews. In fact, local Old Timers knew that this street, this very house, had been built on a burial site. Only 25 years prior, the remains of eight individuals were found in the basement when the previous homeowner was digging out a cellar. More bodies were excavated nearby again in 1902. Local historians and academics debated whether these were the casualties of the Iroquoian-Ojibwa wars of the 17th century, or burials from the lost village of Cahiague.

The following day, Rama First Nation Chief, Alder York, brought John C. Simcoe and Norman Snache to bear witness and to assist in the exhumation. Indian Agent Alexander Anderson also arranged with local funeral director John Mundell to build a suitable coffin, remove the bodies and take them to the reserve. The men had to act quickly, as this area had always been a mecca for “Indian relic” hunters, both locals and tourists.

Many, like Hugh Hammond, publicly reminisced.

“In the early seventies, as a schoolboy, I spent the greater part of some Saturdays and holidays with my playmates in excavating Indian Graves on the lots north of the extension of Mississauga Street, on Mount Slaven, near Orillia Town.”

The same gentleman told a tale of exhuming a giant of a man, picking up his jawbone and passing it over his own head to illustrate how big he was. He also brought the man’s thighbone into school to show his teacher. Hammond was only one of many who combed the area for “artifacts”. By the time Chief York took his place at the edge of the excavation on Friday morning, uncountable treasures as well as the remains of innumerable ancestors had been stolen.

It was obvious that the unscrupulous had paid a recent visit, desecrating the graves further.

“The names of several of those who carried away portions of the skeletons are known and it is understood that prosecution will follow if they are not returned before the end of the week!” The Orillia Packet threatened.

Still, York and his men were able to save the remains of 36 individuals and placed them safely inside the coffin.

Rama Council resolved to give these people a final resting place on Chief’s Island. In the recent past, the community had fought vehemently for privacy and control over the maintenance of this traditional burial ground, frankly telling outsiders who complained of its unkempt state to mind their own business. This was a sacred site not a public park. In fact, Simcoe and Snache dug the grave themselves.

When the day came to bring the ancestors home, it was as if Nature too wished for privacy and control. The waters between the mainland and Chief’s Island, shallow at the best of times, now receded to the point where the scow transporting the bones could not approach. As well, an early morning fog had developed into a thick white curtain shielding inland from beach. Simcoe and Snache, having finished preparing the grave, now had to wade into the water to receive the ancestors. When they turned back towards the cemetery, their figures quickly disappeared into the haze.

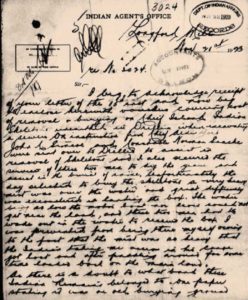

Meanwhile, Anderson, driving over from Longford Mills, never made it to the island.

“I was prevented from being there myself,” he wrote to his superiors in Ottawa. “Owing to the fact that the mist was so heavy that the Indian taking me across in his canoe got lost and after paddling around for some time landed back on the main land.”

The Agent’s letter to the Indian Department’s Secretary (pictured here) stands as the only written evidence of the day. Perhaps words were said to protect and honour those lost individuals whose bones lay in shoeboxes, on cottage mantelpieces or museum shelves. However, by the time the fog burned away and the waters rose, at least 36 ancestors found a sacred and respectful resting place.