Aamjiwnaang Heritage & Culture: E’Maawizidijig help community members learn about dodem identity

By Colin Graf

AAMJIWNAANG FIRST NATION— To find out who you are, you need to find out where and who you came from— that was the inspiration that brought a group of residents together in Aamjiwnaang First Nation in early March.

The meeting, hosted by Amamjiwnaang Heritage & Culture: E’Maawizidijig, featured local historian and writer David Plain and genealogical researcher Diane Aiken, who showed techniques of research and explained the Dodemaag (Clan) System of Anishinaabe families.

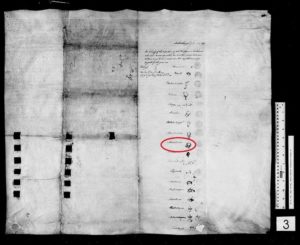

It is possible for many First Nations people to discover their dodem (clan) by searching out documents from the 1800s or even earlier, Plain told the small gathering. The family dodem was always passed down from the biological father, and some family trees can be traced back to ancestors who signed documents with early European settlers, using their dodem symbol next to their names signed in English by a European.

A dodem could not be changed, and in old times, members of the same clan would treat each other as family, even if they lived in a distant village and had never met before, Plain said. Most had animal or tree names because the Anishinabek looked on “all relationships as part of nature,” and members of the same dodem could not marry and have children, and the dodem remained for a woman after she married, he explained. If the father of a child was unknown or the father didn’t have a dodem, the Marten dodem would be given to the child, Plain said.

According to Plain, the change from traditional names to the familiar first and last name in southwestern Ontario was a product of the Christianizing zeal of missionaries in the early to mid-1800s when mass conversions took place. Names would be changed at baptism; often the traditional name would be shortened or translated into English and a “Christian” first name chosen, he said. Between then and around 1880, was a transition period when documents might be signed with the new names and/or the dodem, Plain said. Later, the Anishinabek stopped using dodems and later generations may have forgotten them.

Examining old documents such as treaties and land deeds has helped Plain find the dodems of modern families by looking at how their ancestors drew their dodems for their signatures. Still there are problems, he said. Some dodems are hard to recognize, and some he has seen reproduced on the internet have even proven to be upside down.

“This one might be an antler or a deer, but you can’t always tell,” he said, showing one dodem signature.

Some families, such as the Plains of Aamjiwnaang, have members with differing versions of which dodem they belong to, with different members claiming turtle, bear, or oak membership, he said.

Plain said that not all old documents are digitized and even when museums or archives create a transcript of a treaty or other legal agreement, new problems arise. Plain has found three documents online where his grandfather signed with his dodem, and four more in Ottawa in the National Archives. He has a transcript of the Ottawa items, but they do not include the dodem and simply insert the words “his mark” where the dodem drawing is on the original. He hopes to go to Ottawa to examine those documents in person.

His interest in his family’s history and dodems was sparked because many ancestors were chiefs who signed documents such as treaties, and seeing their dodems was “almost like getting to know them; a connection is made, they become more than just a name in a history book.”

The meeting was held as a feast and celebration of seven years of the heritage group, and Plain said the organizers wanted to see how many people would be interested. He fielded a phone call from a man from Ann Arbor, Michigan, near Detroit, who had seen an online ad for the event. His grandfather was from Aamjiwnaang and he wanted to find his clan.

Members of Aamjiwnaang and other First Nations in southwestern Ontario are starting to use clan names because they want to “rebuild their culture,” said researcher Diane Aiken, who plans to help Aamjiwnaang members figure out their ancestors.

“When I was a kid, we didn’t talk about clans, about anything like that,” she recalls.

Interest in clan identity is growing today, Aiken said, and she finds people are asking her to do more classes on how to do genealogy research. Many want to sort out years of confusion, she said.

“At first, everybody was a turtle, but as time went on, these turtles were bears, eagles, whatever else.”

People used to tell her “well my Dad said we were this or that, but now we want to know accurately.”

Most people in her classes are older, she said, but they are looking to the future and want to settle questions of dodem identity for the younger generations.

Bonnie Plain went to the meeting to try to solve the mystery of her family’s dodem and to pass that knowledge on her children and grandchildren.

“It’s part of our identity, it’s part of our history, it’s part of our future,” she told. “Everybody was curious about this [clan or dodem] growing up, but now people are doing their research and finding out about their family lineage and finding out it’s part of us that’s been missing.”

The dodem carries spiritual importance for Plain.

“That’s who we were before we even got here, and that’s who we’re going to be when we leave,” she added. “It’s important to me to know how to introduce myself properly, and that’s part of my name.”

“This is missing history,” said Nina Antone, whose mother was from Aamjiwnaang and father from the Oneida of the Thames. “I’m rather anxious. I’m 74 and I need to find this out now.”

She explained that determining this history will help settle the trauma she feels from a childhood spent in foster care and a period of motherhood fighting to keep her daughter during the Sixties Scoop.