Ipperwash Summer Series: Learning debwewin from my brother

September 6, 2020, will mark the 25th anniversary of the shooting death of unarmed protestor Anthony “Dudley” George by an Ontario Provincial Police sniper at Ipperwash Beach. The Anishinabek News will feature an Ipperwash Summer Series to highlight the history, trauma, aftermath, and key recommendations from the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry. First Nations in Ontario understood that the Inquiry would not provide all of the answers or solutions, but would be a step forward in building a respectful government-to-government relationship.

For information on the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, please visit: http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/closing_submissions/index.html

By Peter Edwards

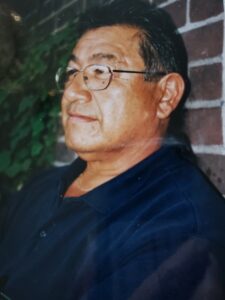

The first time I met Maynard (Sam) George was in the back of the restaurant at Kettle Point, a few hours after his younger brother Anthony (Dudley) George was shot to death by an Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) sniper.

Sam looked like he was in shock. He had been busy at the hospital, identifying Dudley’s body, and then breaking the news to family members.

Sam looked so small as he kept showing me family pictures of Dudley. They were all happy snapshots that seemed totally out of place with the mood that morning.

Sam had never spoken with a reporter before.

“I don’t know what I feel right now,” Sam said. “It’s pretty hard when you see your brother lying on a slab… He’s got a bullet in his chest.”

One of my first questions was about who he blamed for the tragedy.

“I’m not blaming anyone but I need to know the truth,” he said. His voice was so soft I could barely hear him.

Over the next decade, Sam spoke to church and labour groups, First Nations Assemblies, students, teachers, human rights groups like Amnesty International and anyone else who would listen. He sometimes had to sleep in his car because he couldn’t afford a hotel room.

He nicknamed his car “The Truthmobile” and it went in the ditch and broke down – literally – more than once.

One month, he gave 31 speeches. Every time Sam spoke, it was from the heart as he revisited the horrible night we met.

Sometimes Sam and I gave speeches at the same event. I always used notes and Sam only tried that once. He froze up and fumbled and went back to speaking from the heart.

He was always riveting that way.

Sam sued former premier Mike Harris and several members of his government and the OPP for answers. He told me he was quietly offered a large sum of money to drop his wrongful death lawsuit.

I knew without asking that he turned it down.

In the fall of 2002, Harris became the first sitting premier in Ontario history to testify in a civil case against himself, when he was questioned by Sam’s lawyer, Murray Klippenstein, in an examination for discovery.

I was shocked to hear that Sam stood up and extended his hand to the Premier.

By then, a government lawyer had called him a terrorist, despite a court’s finding that the Stony Pointers – including Dudley – were unarmed. I asked Sam how could he shake Harris’s hand?

Sam explained: “It was a hard thing to do, but it was a point that had to be made. … I just tried to show, `We’re not who you say we are. So I’m totally opposite. You don’t know me, really. You think you know me, but you don’t. You know me only as this guy that supposedly is coming to nail your hide to the wall, when really I’m not.'”

The stress of Sam’s search for the truth was getting to him.

He was smoking heavily and collapsed during a speaking trip to Winnipeg. I was afraid he would drop dead if he didn’t slow down but he refused to let up.

He did speak often with Thomas (Tommy) White, a friend and Elder from the Washagamis Bay First Nation near Kenora.

Sam jokingly called him “Akiwenwenzi Kiawatin no” or “Old Man from the North,” while Tommy called Sam, “Akiwenwenzi Shawanoo,” or “Old Man from the South.”

I told Tommy how Sam had kept using the word “truth,” from the first time we met.

Tommy explained that Sam meant “debwewin” when he used the English word “truth.”

It’s a truth that comes from the heart and makes things better.

“Debwewin, in my language, means positive words, positive ways of thinking,” Tommy said. “Debwewin is soft – a soft, honest way.”

“That’s part of healing,” Tommy said. “In our culture, the spirits tell us, `We’ll help you if you do things in a positive way.’ The best advice they (spirits) gave me was, `Don’t use what we’ve given you in a negative way or we’ll take everything back.'”

Sam and Tommy often spoke on the phone.

Sometimes they spoke about serious things, like Sam’s dark, puzzling dreams involving Dudley’s death.

Other times, they joked like schoolboys, including teasing each other with Viagra jokes.

I liked teasing Sam too, like when I told him that producers Jennifer Kawaja and Julia Sereny of Sienna Films had cast the excellent actor Eric Schweig to play Sam’s character in their movie, “One Dead Indian,” based on a non-fiction book I wrote with the same title.

I smirked as I noted that Schweig had been voted as one of People magazine’s sexiest men.

“What’s your point, Edwards?” Sam asked.

I then noted that Schweig was well over six feet tall while Sam was considerably shorter.

“The stress shrunk me,” Sam said.

As things caught on, Sam drew bigger and bigger audiences, including 3,000 for a benefit concert at Massey Hall.

Sam was particularly excited to hear that comedian Charlie Hill was on the bill. Sam told me he made a conscious effort to keep smiling and not to give in to bitterness.

“If I didn’t, I’d just be another angry person,” Sam said.

For all of the joking, there was nothing foolish about Sam. He maintained a deadly serious goal.

“We want Dudley to be the last person to die in a dispute over First Nations territories,” Sam said. “Dudley has left to the Spirit World, and we can only thank him for what he did for the First Nations people at Kettle and Stony Point. But one life lost is one too many, and one can’t put a price on a person’s life, especially since all life is sacred.”

Sam eventually won his public inquiry, which began in April 2004 before Mr. Justice Sidney Linden in the town of Forest, in a hockey rink where Dudley was once a peewee goalie.

The inquiry ran for two years and Sam was always up at the front listening to the evidence.

“One day, on my way back to Forest, I looked at who was driving me, and I realized how much time has gone by because it was my grandson, who was five when all of this started in 1995,” Sam said.

“I never dreamed it would take this long to get those answers because we just wanted to know the truth.”

Sam was proud that one of his grandchildren deposited Linden’s lengthy report into his school library at Kettle and Stony Point. It included several recommendations on how to make things safer in the future.

The last time I saw Sam was in late May 2009. He was in bed and his voice was even softer than usual. He was dying of cancer and asked me to be a pallbearer and to keep telling the truth about Dudley’s death.

Six days later, on June 3, 2009, Sam died in the middle of the night. By then, all sorts of people had grown to love him, including police, politicians and journalists, including myself. When our journey together finally ended, I felt like I was losing a brother.

Peter Edwards is a long-time journalist for the Toronto Star. He is the author of One Dead Indian: The Premier, The Police and the Ipperwash Crisis. He is also the recipient of a Debwewin Citation – an honour given by the Anishinabek Nation.