Ipperwash Summer Series: A short history of the alienation of Stoney Point territory, 1818-1945

September 6, 2020, will mark the 25th anniversary of the shooting death of unarmed protestor Anthony “Dudley” George by an Ontario Provincial Police sniper at Ipperwash Beach. The Anishinabek News will feature an Ipperwash Summer Series to highlight the history, trauma, aftermath, and key recommendations from the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry. First Nations in Ontario understood that the Inquiry would not provide all of the answers or solutions, but would be a step forward in building a respectful government-to-government relationship.

For information on the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, please visit: http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/closing_submissions/index.html

By Laurie Leclair

Many years ago, I read a document written in 1945 by an Anishinabek soldier who had just returned from the war. He recalled how it was late in the afternoon when the bus dropped him off along Highway 21, a short distance from home. Perhaps because of wartime communications or the fact that it all happened so quickly, he was unaware that Canada had evoked the War Measures Act and had taken over his community, the Stoney Point reserve. There were new buildings, strange faces; soldiers just like himself but not from these parts. Stranger still was the realization that what he had fought for, his home and family, his before-life, was somehow gone. It was too late and too dark to walk the five miles to Kettle Point and being emotionally and physically exhausted, he simply fell asleep in a ditch. The answers would come the next day and for years after.

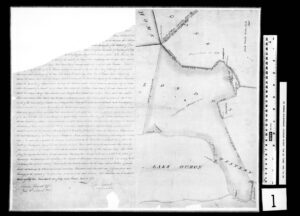

Between the years 1818 and 1827, Anishinabek leaders negotiated with the British Crown over the transfer of 2.7 million acres of land along the southeast shoreline of Odaawaa Gichi-gami [1][Lake Huron] and following the river, which ends at Waawiiyaataan [Lake St. Clair]. On July 10, 1827, Osaw a wip and principal chief Wa wa nosh, the appointed negotiators, along with leaders from the Reindeer, Beaver, Catfish and Crane clans, signed Treaty no. 29, or the Huron Tract Treaty. Chiefs Chemokomon and Quaikeegon, and principal men from Wiikwedong and Aazhoodenat, safeguarded reserves of two miles square each, bordering on the waters of Odaawaa Gichi-gami. Once surveyed out, these lands became colloquially identified as Kettle Point (2,446 acres) and Stoney Point (2,650 acres). Here is what the two tracts looked like from the eyes of Upper Canada’s Deputy Surveyor in 1827:

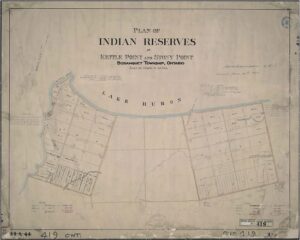

For years, the communities successfully resisted the Indian Department’s pressure to have their territories chopped up into concessions and lots, aware of the fact that subdivision surveys would lead to the loss of more land. Because of this solidarity, the reserves at Kettle and Stoney Point did not receive a registered subdivision survey until Walter Stanley Davidson completed his in 1900. Still, the survey was highly contested and took years to finish. Davidson created several lots and planned for five roads to cut across Stoney Point.

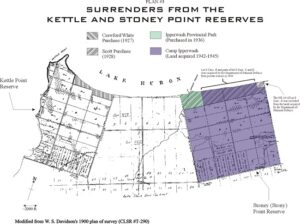

Community leaders chose to reserve land that was both beautiful and able to sustain their people culturally, materially and spiritually. Outsiders also recognized the area’s importance. In 1928, a real estate developer from Sarnia, W. J. Scott, applied to purchase frontage across the entire reserve through Davidson’s ranges A, B, C, D. A surrender vote was held on October 12. Eight months later, Scott paid $13,500 for all four lots along the Stoney Point shore, amounting to 377 acres.

Scott’s purchase proved to be a smart business decision as cottage development bordering Lake Huron began to expand throughout the late 1920-30s. The popularity of the motorcar and accessible roads brought others further out into the country on pleasure drives and picnics. Beginning in 1932, local residents appealed to Ontario to establish a public park somewhere in the vicinity. It was a difficult task, as most of the shorefront properties were privately owned. The province’s Department of Lands and Forests combed the area and decided that Lot 8 Concession A, now owned by the developer Scott, was the most suitable. Eight years after Scott bought all four frontage lots, he severed Lot 8, Concession A and sold it to the province for $10,000. In 1936, after six years of negotiations, Ipperwash Beach became the fourth provincial park in Ontario.

Three short years later, Canada entered the Second World War. Early in 1942, the Department of National Defence (DND) wanted to establish an Advanced Training Base and looked toward Stony Point as a possible site. The area was close to a highway, had hills and valleys, inland lakes, plenty of timber and in the opinion of outsiders, had a very small population. It was not long before DND contacted Canada’s Department of Mines and Minerals, under which the Indian Affairs Branch could be found, asking to purchase the entire reserve, a land base of 2,240 acres. When the Kettle and Stoney Point communities were approached for a negotiation, both were adamant that they did not want to lose any more land. An incredulous Mary Greenbird wrote to Ottawa, “I am the oldest and have rights to say something about our poor children’s inheritance…” She recounted the treaty history and pointed out that her people were already doing their part for the war effort, having young men who enlisted, “but some of them are overseas and some training in Canadian soil yet …while their backs are turned their beloved reservation is taken right from under their parents’ feet?!”

A council was called to discuss DND’s proposal on April 1, 1942. When the vote was held, 59 people stood against and 13 for the proposition. In spite of the results, DND continued its presence on the reserve, running test pits, drilling for wells. Finally, on April 14, 1942, evoking the War Measures Act, an Order in Council was passed granting DND leave to expropriate the lands, all the while continuing negotiations. Ultimately, the community received $50,000 for the land, improvements and the cost of relocating houses to Kettle Point. Although by May, the First Nation had hired a lawyer to contest the decision, expropriation efforts were already underway. The Department employed Oliver Tremaine, a contractor from Camlachie, to conduct the move, a project that began in June 1942 and was completed the following month that year.

There were 16 families directly impacted, 12 had their houses relocated and four, their homes too fragile to withstand the disruption, had to find alternative accommodation. As it was, most of the buildings that arrived at Kettle Point suffered severe foundational cracks and broken sills and windows. Some people, especially those involved in working outside of Stoney Point, did not have time to pack their belongings and once settled, found plates, cups, keepsakes and other breakables destroyed by the bumpy move.

Beginning in March 1943, DND entered into negotiations to purchase the three shoreline lots contiguous to Ipperwash Provincial Park. The result added only an additional 270 acres to the camp but took much longer to conclude, ending with an Order in Council dated October 6, 1944. In contrast, DND acquired the entire Stoney Point reserve, all 2,240 acres, in just 37 business days.

I cannot recall the name of the soldier who returned home that afternoon in 1945, but a quick comparison of a list of Kettle and Stony Point World War II veterans with that of those who lost their homes on Stoney Point in 1942, would have made him either a Bressette, George, Greenbird, Shawkence or a Henry. After spending a fitful night, he got up and followed the trail of crumbling chimney stones and broken glass west to Kettle Point where he would have been told a most unbelievable story.

[1] I am indebted to Dr. Alan Corbiere for his assistance with Anishinaabemowin place names.

Laurie Leclair has been involved in Indigenous issues for over 30 years, and more than half of that time she has worked as an historical researcher for Anishinabek Nation.