Ipperwash Summer Series: The Ipperwash Inquiry and Natural Resource Stewardship

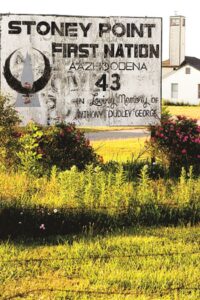

September 6, 2020, will mark the 25th anniversary of the shooting death of unarmed protestor Anthony “Dudley” George by an Ontario Provincial Police sniper at Ipperwash Beach. The Anishinabek News will feature an Ipperwash Summer Series to highlight the history, trauma, aftermath, and key recommendations from the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry. First Nations in Ontario understood that the Inquiry would not provide all of the answers or solutions, but would be a step forward in building a respectful government-to-government relationship.

For information on the 2007 Report of the Ipperwash Inquiry, please visit: http://www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca/inquiries/ipperwash/closing_submissions/index.html

By Cameron Welch and Sarah Hazell

By Cameron Welch and Sarah Hazell

As we approach the 25th anniversary of the Ipperwash crisis, it is important to revisit the recommendations made in the Ipperwash Inquiry Report in regards to the nature of Ontario resource management and the investigation’s proposed path forward. Undeniably, stewardship, sharing, and control of natural resources and their development were at the core of the incidents that gave rise to the Inquiry.

Two outcomes of the Inquiry continue to be relevant today in relation to natural resources management. The first of these is the obligation of the province of Ontario to recognize, respect, and accommodate both Indigenous and treaty rights in the management and regulation of lands and resources. A significant objective of the investigation was to identify potential triggers for the escalation of protests including blockades and other forms of confrontation by First Nations with settler governments and communities and propose methods and remedies of recognition and peaceful resolution that acknowledge the sacred role and relationship that First Nations have with their traditional territories. The second aspect relates to the flow of resources to First Nations and mechanisms that allow resources to be equitably shared in the development of the province. In this article, we will briefly outline how these central issues have evolved since the Inquiry began in 2003 and underscore the work required to avoid the mistakes and outcomes of the past regarding natural resource management and potential conflict between the province of Ontario and First Nations.

From the perspective of Anishinabek First Nations and other First Nations in Ontario, the management of land and resources by the province has resulted in a history of exclusion and denial of rights, a situation that continues to be dismissive of First Nations’ concerns and responsibilities. For their part, the Government of Ontario states that many or most of the Inquiry’s recommendations have been carried out or are in the process of being addressed.

We focus on a couple of the achievements that Ontario points out to the public. The first of these is the creation of the New Relationship Fund. Undoubtedly, this positive development came out of very tragic and avoidable circumstances. The stated goal of the fund is to support Indigenous communities in their abilities to consult on land and resource projects. Many Anishinabek communities have one or more persons whose work is directly supported by the fund. However, the fund is limited, sometimes resulting in direct competition between First Nations and even departments within the same Nation. The fund has become a key source of revenue used to support consultation and lands and resources department staff in many First Nations. Fortunately, after some initial post-election confusion, the current government has resumed support of the New Relationship Fund. However, more work must be done to further support long-term funding arrangements that allow First Nations to attract and retain staff and build capacity in the area of consultation in the long term. After many years of frustration and project failure, stakeholders in development are recognizing that consultation accommodation with First Nations on resource management and development is not only a duty of the Crown but also, when done right, a solid foundation from which to build reconciliation and a successful project for all. The New Relationship Fund is a step in the right direction but is not sufficient in itself to bridge the wide gap between the resources that First Nations bring to the table for consultation, as opposed to settler governments.

In terms of consultation and conflict avoidance, central issues to the Inquiry, it is important to understand the immense pressures that many Anishinabek First Nations, their leadership, and staff are under in relation to government and industry consultation. Hardworking people who do critical and substantial work with very little resources staff many First Nation lands and resources offices. Due to a lack of resources, many leaders and staff are forced to wear many hats in their professional lives by taking on additional responsibilities to bridge the funding gap. Many First Nations have responded to this pressure by working with their own communities to develop consultation laws, policies, and protocols to provide a pathway for meaningful consultation and accommodation. These consultation practices recognize the unique resources and goals of First Nations and must be given credence and meaning above and beyond any consultation policy developed by Ontario that is to apply to all First Nations. The listing of mineral exploration as an essential service in Ontario during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, while many First Nations shut down offices and focused on the health and well-being of their citizens, exposed differing understandings of what is essential and further undermines meaningful consultation and First Nation participation in the development of the resources found in Ontario.

The Inquiry also recommended that the province should work with First Nations to co-develop policies regarding management and resource-sharing initiatives. Little has been accomplished on this complex matter to date. The previous government managed to conclude resource revenue sharing agreements with a handful of First Nations that will soon expire. Ontario continues to fight the Robinson Huron annuities case in the courts, seemingly in opposition to common sense, the spirit of reconciliation, and the Inquiry’s own recommendations. To borrow the wise advice and words of Anishinabek Nation Head Getzit (Elder) Nmishomis Gordon Waindubence, resource revenue sharing will not work. It is only once true sharing of resources is realized that First Nations and settler governments can work together from common or shared ground. It is irresponsible to deny this as a precursor for moving the relationships between Ontario and First Nations forward in an accountable and respectful way.

At a time when a global pandemic gives rise to what so many are referring to as the new normal and systemic racism is being (re)exposed and resoundingly rejected, it is time for us all to reflect on how we can better support one another and build a stronger, more just society in the process.

Dr. Cameron Welch is the Director of Lands and Natural Resources at Nipissing First Nation and a strong advocate for Anishinabek rights.

Sarah Hazell is a member of Nipissing First Nation and an archaeologist with over twenty years of experience in the Middle East, the Canadian Arctic, and Northeastern Ontario. She is an adjunct professor at Laurentian University and the Workshop Manager for the Ontario Archaeological Society (OAS).