Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point and Aamjiwnaang First Nations accept land claim offer this fall

By Colin Graf

CHIPPEWAS OF KETTLE & STONY POINT— Members of Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point (KSP) First Nation voted on Nov. 13 by over 90 per cent of ballots cast to accept a land claim offer from the Government of Canada for money stolen from their ancestors by a British Crown agent in the 1850s.

The land claim was jointly made with Aamjiwnaang First Nation and was approved by the community in Oct. by a similar margin.

The total of the Clench Defalcation (fraud) Claim is $35,728,354, with $17,214,909 (or 48 per cent) going to KSP, according to the Final Settlement Agreement, while $18,513,445 (or 52 per cent) going to Aamjiwnaang, according to a community update provided by Aamjiwnaang Chief Chris Plain last Aug.

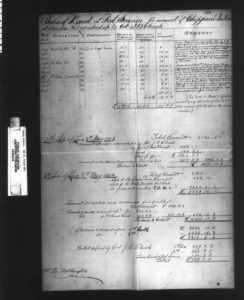

Around £9,000 in British currency of the time had been embezzled from the sale of surrendered First Nations land in southwestern Ontario in the 1850s, under the supervision of the British colonial government’s leading official in the region, Joseph Brant Clench, based in London, according to the Canadian Dictionary of Biography.

The money came from the 1852 surrender and from sales of surrendered land in 1853-4 from the “Chippewas of Sarnia,” according to the Agreement’s text. Ancestors of today’s Aamjiwnaang and KSP First Nations were in that group.

The Claim has been “a long time in coming” according to Aamjiwnaang’s Council Clerk Lynn Rosales. The Claim was originally presented in 1974, and was accepted by Ottawa for negotiation in 2011, she says. The community has had a research team working on the Clench Defalcation for many years, Rosales adds.

In 2015, Canada offered just over $28 million, according to Chief Plain’s Aug. update. Problems arose over the division of the funds, and in Oct. 2018, the two communities agreed to mediation. The offer was raised to its final level, according to Chief Plain, and a 52-48 split was agreed to 2019, he states.

KSP Chief Jason Henry told his community in a video update in Oct. that the dispute was resolved when the federal negotiator arranged to increase the compensation amount so both sides would come away with more money in spite of the division.

“We can’t have this rift with our sister First Nation,” he said.

Clench, a colonial British functionary, was appointed “agent for the sale of Indian lands” in southwestern Ontario in 1845, according to a report prepared for the Chippewas of the Thames in 2000 regarding another Clench Claim.

In 1854, the Governor-General of Upper Canada ordered an inquiry into the handling of land sales, after receiving complaints about Clench’s work. Two accountants appointed to look into the matter found Clench’s accounting was “almost worthless” and that he was confined to bed by illness and was suffering mental deterioration, according to the report.

He was removed from office that year and government policy was changed to require all payments to be deposited in a bank, according to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. An inquiry held the next year in London found that Clench’s wife and two of his sons had purchased properties with monies belonging to the Indian Department, according to the Dictionary entry.

Disclosures during the investigation “led to alienation between him and his family and to further deterioration of his health,” the Dictionary article’s author, now-retired high school teacher Daniel J.Brock, wrote. Clench left London to live in a nearby rural area and died at a London hotel in 1857 from “an apoplectic fit,” Brock wrote.

A newspaper obituary described him as “an upright, good, and just man” and, while viewing him as “the victim of others’ villainy,” saw a tragic flaw in “his want of firmness and discretion.” According to the Dictionary article, at the time of his death, he still owed the Indian Department more than £6,950.

No one can be certain today whether Clench himself or his family were responsible for the embezzlement, says historical researcher Laurie Leclair, as both suffered prejudice from other members of the British colonial establishment owing to his wife’s Jewish ancestry.

“In provincial London being Jewish would not have helped” the family, says Brock.

A number of Jewish people did come to London, but most converted to the Church of England, he says. One of them even became a Bishop, Brock adds.

The “standard story” is that the money was actually misappropriated by his wife and sons, but “we don’t know how much of that is built-in anti-Semitism,” according to Leclair.

There was not much control over the handling of money being collected by the government in those days, she says, and many First Nations in the southwest were affected by the frauds.

The historical record shows Clench began as a junior employee of the Indian Department as a young man, fought in the War of 1812, but had trouble climbing the ladder in the Department, being passed over several times for higher positions, writes Brock in the Dictionary article.

Another factor that may have affected his employment was Clench’s own First Nations’ ancestry. His first and second names Joseph Brant are testimony to the fact one of his grandfathers, a British Lieutenant named Keghneghtego, was descended from the Mohawk Brant family. The most famous of the family, Joseph Brant, led the Haudenosaunee people to fight for the British during the American Revolutionary War and later settled with many of his people in the territory that includes today’s Six Nations territory.