Court case deals with history and identity

A recent court case, held virtually in North Bay, created quite a controversy and raised questions about the legitimacy of the Robinson Treaty of 1850 and the rights of local Indigenous people to hunting and fishing in the region.

The case concerned 54 individuals who had been charged with violating provincial hunting and fishing laws, as well as commercial fishing laws of Nipissing First Nation. Eight of the men were commercial fishermen from Nipissing, and the others were from the Sturgeon Falls and Mattawa areas who had been charged a number of times over the previous 15 years with similar offenses. The defendants did not deny the charges but claimed that they were within their rights as members of the Amikwa First Nation. Further, they alleged that those who signed the treaty in 1850 had no right to do so, as they did not represent the Amikwa First Nation, whose traditional territory, they claimed, stretched from Sault Ste. Marie all the way to the Atlantic Ocean.

These arguments caused real concern in the communities affected, and there was some anger that the courts would even hear the case. But the two witnesses brought forward by the claimants were quickly dismissed by the judge, Justice Erin Vainepool. An American human rights lawyer was brought in to provide historical evidence for the Amikwa First Nation claim but admitted on the stand that he had never heard of the Amikwa before being asked to give his expert testimony.

The second witness was Stacy McQuabbie from Henvey Inlet First Nation, who had worked for many years on his family history, and claimed that he was a member of the Amikwa First Nation, and that his family name was Amikwabi. His research was not accepted by Justice Vainepool, as it was, as she described it, “hearsay”, and inevitably biased and subjective. The lawyer for the 54, Michael Swinwood, argued that the Robinson Treaty had been signed by Potawatomi leaders, and not by the people who actually occupied the land.

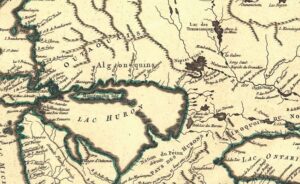

Although doubt was cast on the very existence of the Amikwa and it was thought that nothing could be known about the early history of the Indigenous history of northern Ontario, neither of these assumptions is accurate. Accounts written in the 17th Century refer to the Amikouai, who were living on the north shore of Lake Huron west of the French River. In 1640, a Jesuit explorer, Paul LeJeune, described the peoples he came across as he travelled up the east coast of Georgian Bay and along the North Shore.

“Leaving [the Huron], to sail farther up in the lake, we find on the North the Ouasouarini; farther up are the Outchougai, and still farther up, at the mouth of the river which comes from Lake Nipisin, are the Atchiligouan. Beyond, upon the same shores of this fresh-water sea, are the Amikouai, or the nation of the Beaver. To the South of these is an Island in this fresh-water sea about thirty leagues long, inhabited by the Outaouan. After the Amikouai, upon the same shores of the great lake, are the Omisagai, whom we pass while proceeding to Baouichtigouian, that is to say, to the nation of the people of the SauIt.”

It is clear from this account that the Amikouai, or Amikwa, were just one of the groups living in the region, and their lands certainly did not stretch from the Sault to the Atlantic Ocean, as Michael Swinwood claimed on behalf of the defendants. In 1670, another Jesuit, Claude Dablon, while describing the mission among the Ottawa on Manitoulin, talks about the other “tribes” in the area who were connected with the area.

“After surveying this entire Lake Superior, together with the Nations surrounding it, let us go down to the Lake of the Hurons, almost in the middle of which we shall see the Mission of Saint Simon, established on the Islands which were formerly the true country of some Nations of the Outaouacs, and which they were forced to leave when the Hurons were ravaged by the Iroquois. But since the King’s Arms have compelled the latter to live at peace with our Algonquins, part of the Outaouacs have returned to their country; and we at the same time have planted this Mission, with which are connected the peoples of Mississagué, the Amicouës, and other circumjacent tribes…”

These groups, the Outchougai, the Atchiligouan, and the Omisagai, as well as other family groups, joined together as the Ojibwa, according to historian Peter Schmalz and other anthropologists. The earliest records show that as far back as 1615, Samuel De Champlain stayed with the Nipissing at their village and encountered the Ottawa from Manitoulin at the mouth of the French River. There is no mention of the Amikwa, as he did not travel further west. But, had that people been as important as Swinwood claimed, they would certainly have been mentioned.

Swinwood proved to be an indifferent historian when it came to describing the signatories to the Robinson Treaty in 1850 as Potawatomies. He stated that all of the Algonquin peoples who lived in the region were descended from the Amikwa, and only those descendants were authorized to sign a treaty. Instead, he claimed, it was signed by only Potawatomies. However, prior to the negotiation of the Robinson Treaties, a number of inquiries were made about those with whom a treaty would be made. In 1849, one of these reports noted that the various groupings were very aware of their boundaries and traditional hunting, trapping and fishing lands, as each one “…[possess] an exclusive right to and control over its own hunting grounds; the limits are generally well known and acknowledged by neighbouring bands; in two or three instances only, is there any difficulty in determining the precise boundary between adjoining tracts, there being in these cases a small portion of disputed territory to which two parties advance a claim”.

The claims put forward by the 54 individuals in the court case before Justice Vainepool seem to have been based on a misinterpretation of the historical evidence, and it was clear from the confused and inaccurate arguments put forward by their lawyer and the American expert witness that very little, if any, research had been done in preparing their case. The defendants were found guilty of the charges and Justice Vainepool levied fines ranging from $250 to $750.