The Treaty of Niagara and the Belt of the Covenant Chain

By David Shanahan

As soon as the Royal Proclamation had been issued in 1763, Superintendent of Indian Affairs William Johnson convinced Algonquin, Caughnawauga and Nipissing warriors to travel throughout the Indian Territory to show it to the tribes and call them to Niagara for July of the following year. At least 24 Nations were represented at Niagara by more than 2,000 chiefs, sachems and warriors. They came from all areas of the Great Lakes region, north and south, from as far east as Nova Scotia, and it is possible that there were even delegates there from the Lakota and Cree. It was undoubtedly one of the greatest and most representative gatherings of the First Nations that had been seen.

In accordance with Johnson’s intentions, every meeting held over those few weeks was conducted with the exchange of wampum and pipes, as the parties discussed the need for the restoration of peace, and especially of trade, as the preliminary to a new relationship between Britain and the nations.

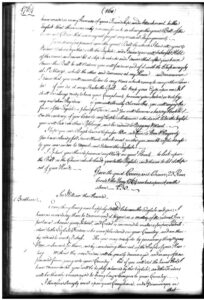

At Niagara, Johnson presented two wampum belts to the Western Indians, which were designed to seal, in their own terms, the results of the Congress. The Covenant Chain Belt was given at the end of the gathering, on July 31, 1764. Johnson summed up the events of the previous days’ talks and noted that all that remained was to “exchange the great Belt of the Covenant Chain that we may not forget our mutual Engagements.” In his speech to “the Western Nations, Sachems, Chiefs & Warriors”, Johnson mixed warnings and promises.

“…now only remains for us to exchange the great Belt of the Covenant Chain that we may not forget our mutual Engagements. I now present you the great Belt by which I bind all you Western Nations together with the English… but keep your eyes upon me, & I shall be always ready to hear your Complaints, procure you Justice, or rectify any mistaken Prejudices. If you will strictly Observe this, you will enjoy the favour of the English, a plentiful Trade, and you will become a happy People. On the contrary, if you listen to any People whatsoever who do not like the English you will lose all these Blessings, and be reduced to Beggary & Want. I hope you are a People too side to prefer War and Ruin to Peace and Prosperity”.

This Belt was to be kept, one end at St. Mary’s and the other at his house. The Western Chiefs decided instead that their end should be at Michilimackinac, “as it is the centre where all our People may see it.” Both parties encouraged the other to hold fast to the Belt and think always of what it meant.

The other Belt exchanged at Niagara was the Presents Belt, the promise of continued trade and communication between the Nations and the British. The two belts were kept as promised by the First Nations and were brought out at important gatherings, such as the 1818 Drummond Island gathering, the 1836 meeting at Manitoulin Island, where Governor Bond Head explicitly referred to the Niagara congress in his speech to the gathered Nations, and in later reports on the Indian Department, when Government officials reported on the Nations displaying the Belts and the original copies of the Proclamation as reminders to the Crown of their past engagements. Johnson held further meetings with Nations not present at Niagara in order to bring them, too, into the Covenant Chain. These were held at Detroit in 1765 and at the Treaty of Lake Ontario in 1766.

Unfortunately, whereas the Nations remembered and understood the significance and symbolism of the Belts and the events at Niagara which led to them being exchanged, the Crown officials soon forgot their meaning and importance. In the absence of written documents, signed Treaties and agreements, the Crown came more and more to see the Royal Proclamation as a unilateral declaration by the Crown of the new order which would exist following the defeat of the French and not a preliminary paper which required and received, First Nations consideration at Niagara and the later gatherings. The Treaty of Niagara was remembered only as an event that led to the cession of certain lands along the Niagara River, whereas it was far more important, more significant, and more meaningful than that. If only the Crown had remembered and understood.