Lakehead University explores treaties during Treaties Recognition Week

By Rick Garrick

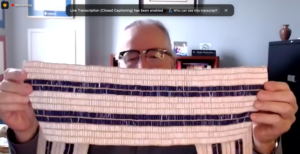

ORILLIA — Chippewas of Georgina Island’s Brian Charles spoke about four wampum belts, including Two Row Wampum and Dish with One Spoon, during his virtual Wampum Belts Woven Through Anishinaabe History presentation on Nov. 5 for Lakehead University’s Treaties Recognition Week.

“One of the pieces that gets talked about quite often for Indigenous peoples, and certainly Eastern Woodland and probably all across North America, is that Indigenous peoples didn’t write anything down, didn’t have a writing system, which is completely false,” says Charles, who has researched and assembled with a group of Knowledge Keepers a repository of wampum belts. “There are petroglyphs, pictographs, birch bark scrolls, and one of the ways of writing things down was wampum, to create a record, to create an archive, a way of storing knowledge and storing information so that knowledge could be handed down to future generations.”

Charles says wampum beads are most commonly made from the shells of quahog clam, an East Coast clam that was harvested for food.

“One of the things that is unique about this particular shell is that really wonderful purple colour on the inside of the shell,” Charles says. “After harvesting the food, then there was a series of shells leftover. If we look at that particular shell, the outside edge is very fine so you have a natural cutting or scraping tool. Smaller shells can be used as a spoon, larger shells used for a cup and larger shells used for a bowl.”

Charles says broken shells were used for the creation of purple, white or multi-coloured beads and ornamentation, such as earrings, bracelets, or necklaces.

“So we see those beads put on strings … and strung in a certain way so they would begin to record council events,” Charles says. “When a council was held, strings of wampum would be given out to all of the participants, all of the leadership from the different groups, as a form of acknowledging that they had participated in the council, a record of their attendance, and then by accepting that string of wampum, that they had pledged to uphold any of the decisions that came out of those individual councils.”

Charles says as the system evolved the wampum were woven together to create wampum belts.

“They were used across many different nations all throughout the Eastern Woodland,” Charles says. “So a vast section of North America as we know it today was participating as Indigenous nations in wampum diplomacy — the wampum then would be used between two or more groups to record relationship, wampum diplomacy, inter-national relationships originally between Indigenous nations and then as contact takes place, European nations that arrive here.”

Charles says the European nations recognized that the wampum system of diplomacy had been in place for a long time before they arrived between the different nations of Indigenous peoples across the Eastern Woodland.

“And they began to participate fully in the diplomatic system that was already in place within these territories,” Charles says. “The French began to exchange wampum. When the British arrived later, they began to fully participate in the system of diplomacy that was already existing in this land before their arrival, and they too began to exchange wampum with Indigenous nations.”

Charles says the samples of wampum beads that he shared during his presentation were authentic quahog shell beads while the wampum belts he shared were reproductions.

“So we can use [the reproduction wampum belts] to take out for teaching,” Charles says. “People can hold them in their hands, people can see not just photographs or stills but actual physical recreations.”