Serpent River First Nation still feeling effects of acid plant, a simmering mistrust

By Leslie Knibbs

SERPENT RIVER FIRST NATION– In 1957, Noranda Mines began operation of a sulphuric acid plant in Serpent River First Nation (SRFN) to process the uranium mined from the Elliot Lake area. The plant remained open until 1963. Now, 58 years after the acid plant closed, the issue of environmental damage remains unresolved, as is the matter of compensation to the First Nation.

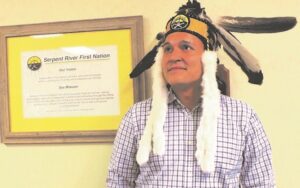

According to SRFN archives, the establishment of the plant was promoted by the government and Noranda alike as a means “of bringing prosperity to our community and it may have for a small bit,” SRFN Chief Brent Bissaillion said recently.

“The environmental cost [of the plant] has been greater than the minor benefits received at the time,” he added.

The devastation resulting from the plant remains today.

“We are still unable to eat the fish in our rivers, and use the land set aside for us to use,” he explained.

The plant was situated on waterfront property contaminating the land and the water in the area. Although many attempts to clean up the contamination have taken place over the years, long-term effects are still a nagging issue in SRFN. One distressing sign of this occurred a few years back where the Pow Wow grounds were moved because of the close proximity to the old plant site. Chief Bissaillion elaborated when asked about the long-term effects.

“Loss of land – long-term detrimental health effects (some of the highest cancer rates in the province) and shortened life spans for people who live on SRFN. The acid plant is also a branch of the overall issue, and that’s mining in Elliot Lake, and the effects that it had on our river system, the loss of our inherent homeland that is the City of Elliot Lake, they moved us when they discovered uranium.”

According to Chief Bissaillion, there was only minor consultation done prior to the building of the plant.

“At the time, I believe it was done by the Chief and Council, with some minor community meetings, but again, with the powers of the Indian Agent and Federal Government at the time… I ask the question, did we really have a choice? When your people are starving, hurt, and living in enforced poverty… you will take any opportunity to rise out of that. And with a federal government saying that it’s good to go, and don’t worry, etcetera. I think now, we are better suited to understand the choices we make, and our community members are wary of any industrialization because of this project.”

Not only are there long-term effects on the environment of the SRFN community, but perhaps just as important is the simmering cauldron of mistrust created by the establishment of the plant hindering any future projects.

“We are currently doing monitoring and site testing around to ensure we can understand the full scope. Now that COVID-19 is slowing down in Ontario, we are continuing the engagement, and updating the community on where the remediation project is at, but again, awareness is key, and many people are unaware of the history of mining development in Serpent River and how the effects of that continue to haunt us to this day. We still can’t use it for anything, the land is unusable unless we remediate it and they tried to do it before. The Spanish dump has tons of debris in it from the first remediation, but still more work is done, and it truly may never be fully repaired,” he explained. “I am hoping that by raising awareness of this, people in our surrounding area can understand, and advocate for a resolution to this problem. The plant closed in 1963, but we are still… in 2021, living with the effects, and still trying to fight for our restitution on this issue.”