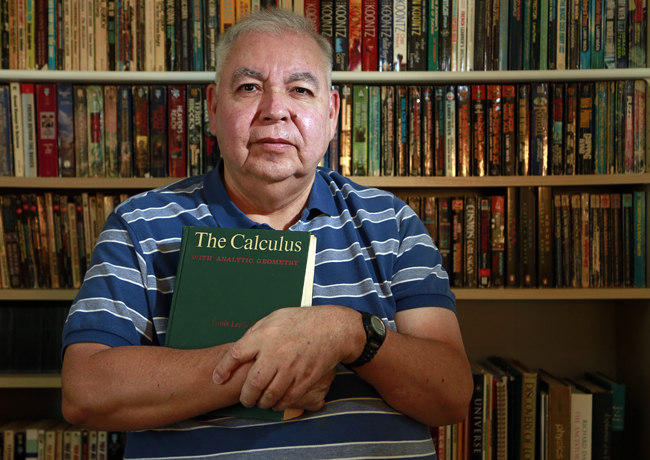

Alderville man one of the smartest people in Ottawa

– Photo by Julie Oliver, Ottawa Citizen

By Chloé Fedio

The Ottawa Citizen

OTTAWA — Alfred Simpson picks a worn copy of Pinocchio off a bookshelf in his Vanier apartment and memories of his early education in a one-room schoolhouse on the Alderville First Nation reserve rush back.

“I didn’t learn the alphabet until I started Grade 1. I finished this book by the end of Grade 2 — it took me two years to learn how to read,” he recalls.

He didn’t realize that he was behind other students his age until he started taking a bus 30 kilometres to the off-reserve school in Cobourg, Ont., in Grade 7. That was the year he learned cursive writing.

But it wouldn’t take long for Simpson to catch up, then quickly surpass his peers.

That’s because Simpson is a certified genius.

The 64-year-old is the membership officer for the Prometheus Society, a high-IQ association that admits only those whose scores place them in the 99.997th percentile. (Simpson has been part of a handful of high-IQ societies. Perhaps the best known is Mensa, relatively much less discriminating in admitting the 98th percentile, or top two per cent.)

Simpson was in high school when he first realized he had an exceptional mind, one that could quickly grasp concepts and understand them on a higher level without much guidance.

“That is strange, that we’re all created differently. That was an awakening,” he says.

While extraordinary intelligence might seem like a superpower, it also comes at a cost.

“The hard part is the loneliness. I live alone. I have books and very few friends,” he says. “The only thing that makes the loneliness bearable is family.”

A framed photo of his son and daughter, along with their spouses and children, hangs on the wall of his small apartment. The love of his life died of carbon monoxide poisoning in the spring of 1986, when she pulled over to rest while driving back home to London from Toronto alone.

They had been married nearly 15 years.

“She fell asleep and didn’t wake up,” Simpson recalls. “Total disbelief, total denial for months after what happened.”

As a grieving single father, he joined Mensa with his two young children who had just lost their mother. His son and daughter had both achieved the requisite IQ scores.

“It was an organization that sort of filled the void.”

With other members of the group he was able to broach topics that he might otherwise avoid.

“Nobody would say, ‘Pardon?’ or ‘Sorry?’ or ‘What are you talking about?’ They would actually understand what you are talking about.”

His son, Taynar Simpson, was only ever a passive member, occasionally reading the Mensa newsletter.

He was surprised when he first found out about his father’s genius status.

“I didn’t believe him,” Taynar Simpson says. “Through time, I figured out he was.”

In day-to-day life, he says, his dad is a “regular guy.” But when it comes to science and computers, his intelligence shines through. He enjoys long talks with his dad about the origin of the universe and coming up with arguments to debunk the dark energy theory.

Most of all, he says, his father is a caring, supportive man who has always been there to offer advice.

The elder Simpson has had various computer programming and coding jobs over the years, but he now runs his own independent business — Totem Consulting — designing websites, databases and applications from home.

It was a career he initially resisted.

Simpson was introduced to computers as a first-year math student at the University of Waterloo in 1967.

“There was something funny there called computers,” he recalls. “I was hooked. I spent half my time in the computer lab.”

But his humble roots and immense respect for his first school teacher in Alderville — who had been tasked with juggling subject matters for all students up to Grade 8 — led him to pursue that vocation himself.

“All my life I wanted to be a teacher,” he says.

After graduation in 1971, he went on to teachers’ college at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay.

“Everything was fine until I started student teaching. I hated it. I had an aversion to telling other people what to do. I don’t like to enforce my will on anyone.”

He soon found satisfaction in giving orders to inanimate machines.

“The thing I like about computer programming is that computers do what you tell them to do, not what you want them to do. That’s something I learned very early.”

He estimates he has logged 95,000 hours of computer time — that’s 17 per cent of his 64 years.

Taynar remembers his father teaching him about coding as a child on an Apple II. “You could sit him in front of a computer 20 hours a day and he’d be happy,” he says.

Simpson’s computer crashed in 2000. Since then, he keeps a backup of his emails on a 15-gigabyte USB key in his pocket. He’s up to 100,000.

“In case the whole house burns down,” he said. “I don’t leave the house without it. Maybe I’m paranoid, but computers crash.”

His first computer-related job was in Ottawa as a programmer for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in 1972. He has also worked in London and Toronto, doing various jobs as a programmer and operating systems administrator.

“He’s a master of so many languages that have gone extinct,” his son said. “He does keep his skill set sharp.”

As Simpson’s 65th birthday approaches, his life can be best described as peaceful.

He doesn’t smoke or drink — his grandmother’s influence.

“I have never smoked a cigarette in my life. I have never even had a teaspoon of beer. I made the decision very young.”

He traded his Hyundai Pony in for a bus pass 25 years ago.

“I just thought it wasn’t environmentally sound to have a car in the city. If I go back to the reserve, I will get a car again. But here in the city I feel it’s wrong if I can get around on public transit,” he says.

He has kept a journal for 40 years. “There are 40. One a year,” he says, pointing to stacks of notebooks on a bookshelf. Another bookshelf is filled with science fiction novels penned by Dean Koontz, Isaac Asimov and Alan Dean Foster. He points to his favourite collection: the Tarzan series by Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Lately, he’s being spending more time on passion projects. Music plays softly in the background as he works. It took him a week to build a website about his personal history for his children and grandchildren. He also published a website based on his grandmother’s research about the Rice Lake Indians.

“The computing keeps me really, really busy,” he says. “I’m always looking for something new to do.”

(This story first appeared in the April 13, 2013 edition of the Ottawa Citizen.)