Story-telling creates extended communities

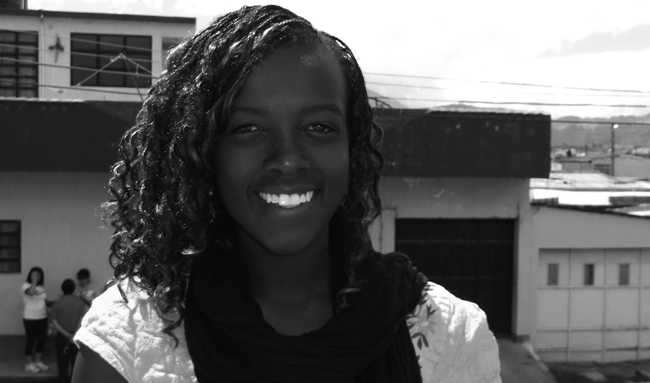

By Faith Juma

By Faith Juma

For me, stories are full, pregnant with meaning.

They bear life, experiences, and answers in their innermost parts. Stories open the door to a deeper way of engaging this world; they lead us into the Spirit World, to our ancestors and the heart of our Creator.

Stories are a source of guidance; they exist to comfort and confront, to move us from security to humility. The act of story-receiving and telling is an act of surrender. To receive a story is to allow a dialogue to take place within, to be brought to a new awareness, and to leave changed.

In the past year, I was fortunate to be invited into part of North Bay’s storytelling community. In my time learning and working from Nipissing University’s Aboriginal Office, as well as being in community with Aanmitaagzi Art Studio, I heard and received several stories that moved me deeply. This fall I have been living in the Western Highlands of Guatemala, in the town of Quetzaltenango. Here I have had the similar opportunity to sit with many different storytellers, and receive from them.

Two stories in particular have settled within and become a part of me. Both rise out of bodies of water that are important to their surroundings. The first is from Lake Nipissing, and the second from Lago Chie K’bal, a sacred lake in the Western Highlands.

The first story rises out from Lake Nipissing and moves over the Manitou Islands, telling a tale of loss that inspires strength and courage. In contrast, the story of Lago Chie K’bal falls from the heavens, bringing with it a message of man’s limitations, and demanding stillness and humility in response.

In receiving these two stories, they have resonated in me, creating a dialogue with my daily thoughts and intentions. At the time I heard the Nipissing story my heart was being prepared for what was to come. Here in Quetzaltenango, when confronted with the harsh realities and harsher history of the communities I live among, Lake Nipissing speaks “courage” to me.

And yet, in moments when observations of struggle turn into observations of inexplicable beauty, the waters of Lago Chie K’bal fall on me. They bring me to a place of stillness, that I may give thanks and be humbled.

In allowing these stories to move within me and take root, I have been given a sense of security and humility in my new surroundings. These stories hold me accountable. I have come to embody them. In receiving them, they have given me an awareness of my innermost parts.

In their essence, stories are birthed to be shared. I carry these stories with me, and also those who told them. I carry with me a part of North Bay’s Anishinabek community, I am forever held by Nipissing’s waters. Here in the Highlands, through receiving the story of Lago Chie k’bal, I am now the storyteller; I am now an extension of the Maya-mam community from where the story came.

So what is the importance of a story? In my Bantu tradition, we are bound together in the Spirit of Abuntu, meaning we can only exist in relation to each other; I am because you are. Through receiving these two stories I have stepped into a relationship of Abuntu with the communities that shared them with me.

Faith Jenifa Ndenga Juma, is from the Bantu-Luyah Oral Tradition in which she is a story-receiver and teller. A recent graduate of Nipissing University’s Education program, she is currently on a teaching and research internship in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, where she works in cultural education projects in Maya communities. She returns to Canada in January to pursue a Master of Education at York University.