Woman paddled 600 km. to Hudson’s Bay post

By Laurie Leclair

In late July, Marie Bussineau left the hunting and fishing camp she ran in the Agawa Bay area and travelled up to the Kenogami River to reconnect with family and to celebrate.

Tuesday, July 24, 1917 marked treaty day for the people at Long Lac. The Bussineaus were related through marriage to the influential family of Nick Findlayson, the Chief Factor. Nick came from Fort William. His wife Jane was a member of the Pic River First Nation.

The families were close enough and the event of such interest that Marie made the trek with her two young sons, a nearly 600-kilometre journey. We do not know how long it took her, but her diary, which usually chronicled daily events at her hunting camp, remained blank between July 1st and August 10th.

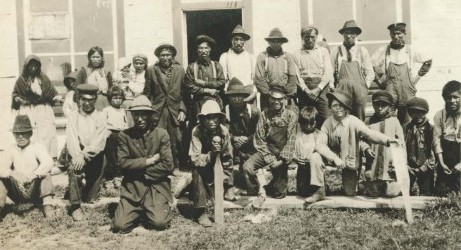

Others came to join the Long Lac community including Mr. and Mrs. McLeod from the trading concern Revillon Frères, and Katherene Pinkerton, a celebrated American wilderness author who took the photographs that document this day.

To allow families to purchase supplies and gifts, the treaty was taken at the Hudson’s Bay Post, a site marked by a cluster of ten single and double-storey wooden buildings, dominated by a very tall flag pole and an ancient fur press. The fort sprawled over 1,000 feet of shoreline, with clay banks on one side and stony outcroppings closer to the docks where once large York Boats moored to unload trade goods and supplies.

Those present were solemnizing their relationship with the Crown, taking part in the 67th year of Robinson Treaty payments, but if Pinkerton’s photographs lend any clues to the true meaning of the day, they show that receiving the annuity, although important, was secondary to celebration and community spirit.

People gathered for men’s and women’s sports competitions, ball games and canoe races, trading and socializing. Some women, like Jane Finlayson, sat by the waterside and gazed across at the Making Ground River while preparing hides to be sold to the traders or sewn into moccasins. The adults are smiling and the children’s mouths are wide with laughter when organizers scattered handfuls of sweets into the long grass and all was happy confusion as they searched for their prize. As evening wore on, smoky cook fires dotted the rocky shoreline, men lit up their pipes and the families feasted. And always the dogs, tiny packs of silent, hopeful dogs sat and waited.

The fort was constructed on the site of an ancient gathering place, situated at the confluence of the Kenogami River and Long Lac, a stopping point along the portage route that led from Lake Nipigon via Pic River to Lake Superior. The French knew about the importance of this area as early as the 1660’s. By 1820, the site became a Hudson’s Bay Company post, and by Mary’s time, a co-partnership with Revillon Frères.

The post was relocated in 1921 and the grounds all but forgotten until 1964 when a group of archaeologists led by Kenneth Dawson spent a rainy season excavating. The team found thousands of artifacts, but frustratingly, most of them came from surface collecting, things that had been lost or left behind. There were the usual items one finds on historic sites: Saws, cooking utensils, beads, buttons, pipe fragments, glazed pottery, window glass and shot, rolls of birch bark left for emergency repairs to canoes, etc…

But along with these utilitarian items were found things of joy and celebration: A child’s toy shovel still bearing its white paint, dolls, and pieces of harmonicas, concertinas and jaw harps. It is easy to imagine that with the addition of a drum and fiddle plus a chorus of happy singers, the air would have been filled with music on that cool summer evening nearly 100 years ago.

Laurie Leclair is a principal of Leclair Historical Research and a treaty researcher for the Union of Ontario Indians.