A gift from Standing Rock

By Samantha Restoule

NIPISSING FIRST NATION –On an unsuspecting Monday afternoon, an unexpected visitor stopped by the Union of Ontario Indians head office attributed to what seemed to be some sort of cosmic event.

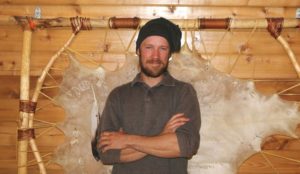

Jacob DiGirolamo, from the northeastern state of Maine (USA), needed to stop for Wifi and directions on his way back home and just happened to be driving through Nipissing First Nation. He shared that he did not know where he was stopping, or why he was inclined to stop at this particular place.

DiGirolamo was driving back to Maine from Standing Rock, North Dakota, where he spent three weeks camping and supporting the Standing Rock Sioux in their fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Briefly, the Dakota Access Pipeline (also known as DAPL) is a 1,885km crude oil delivery pipeline running from Bakken, North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. If completed, it will transport as many as 570,000 barrels of oil per day. The construction of this pipeline poses a huge threat to the environment including clean drinking water supplies, not to mention it infringes on Indigenous land and ancestral burial grounds. Since April, people from all the four directions have come together at Sacred Stone and/or Oceti Sakowin Camp to put their bodies on the line and to fight to protect Mother Earth.

DiGirolamo discussed what lead him to go to Standing Rock; DAPL started becoming a prevalent conversation topic amongst his peers, and after hashing out the issues and talking about what was going on, somebody in his community decided that they should pool some donations together, buy a truck, and send it out there. When it came down to who was going to drive the truck, DiGirolamo realized it was a possibility for him and didn’t look back after that.

Unfortunately, things did not transpire as expected, and the original plan dissolved.

Fortunately, this downfall was the catalyst to him realizing he had the agency to do it himself.

“I was the one who ended up organizing my own trip and pooling donations,” noted DiGirolamo. “We had a cider party fundraiser in my town – which is something I do every year, but I realized it was a resource I could use to leverage towards getting donations.”

DiGirolamo filled up his pickup truck with a couple hundred pounds of storage vegetables from local farms, some tools, warm clothing, and headed out.

“I tried to figure out the most advantageous things to bring from the northeast to North Dakota,” stated DiGirolamo. “I also made an effort to get culturally aware before leaving.”

DiGirolamo poignantly described the fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline – popularly known as NoDAPL.

“It’s an important concentration of a cultural and ecological awakening where a lot of people are realizing that we can’t keep living on this planet the way we’re living and that we need to start paying attention to the older ways that allowed people to live on this planet for thousands of years,” stated DiGirolamo. “The First Nations peoples were here and they managed to coexist with nature and collaborate with nature for millennia before the second man arrived; it’s been a very short run with the colonists here and it’s not looking so good. It’s not very hard to see that, and I think that a lot of people are recognizing that we can’t keep going forward – but we don’t know how to go back. ”

When asked to describe what the scene and life looked like at Sacred Stone camp, DiGirolamo spared no detail.

“It’s kind of surreal because on your side of the Cannon Ball River, you’re looking at this crazy mixture of campers [RVs], tents, 20ft tipis, long houses, and Mongolian yurts that were handcrafted by a single extended family in Mongolia,” noted DiGirolamo. “They had hand-painted cloud and water motifs on the rafters on the inside, felted wool insulation, and braided horsehair to tie them together.”

As for daily life at Sacred Stone, DiGirolamo explained that it was like a village: there was one Sacred Fire, one kitchen, one herb tent, and so on. Everybody pitched in and did their part. There was also a lot of prayer, reverence, and ceremony. If Sacred Stone was a village, Oceti Sakowin was a city.

“It was huge, it took about 30 minutes to walk from one end to the other,” recalled DiGirolamo. “And it took a good 40 minutes to walk from Sacred Stone to Oceti.”

The reason DiGirolamo’s visit to the UOI offices is some kind of cosmic event is because eight days after his visit, the Trudeau government approved the expansion of the Kinder Morgan pipeline which will run from British Columbia to Alberta. The expansion would increase the amount of oil transported from the current 300,000 barrels per day to 890,000 – that’s almost triple. This increases risks of pipeline ruptures, increases oil tanker traffic (huge ships that cause a lot of pollution) and the expansion of Alberta’s tar sands. In short, it is being predicted that what has, and continues to take place in Standing Rock will happen in Canada, too.

Chippewas of the Thames, one of the Anishinabek Nation’s 40 First Nation communities has already taken a lead in this battle to protect our Mother Earth. It’s Canada’s turn to fight now. Maybe Jacob’s visit happened for a reason. His sharing of knowledge and experiences was certainly a gift, and his visit – certainly not a coincidence. Chi-Miigwetch to him for taking action and being a Water Protector.

Protect the Sacred – because you cannot drink oil.