The secrets of the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs

By Laurie LeClair

Mii dash geget Nenabozhoo maajitaad ozhi’aad biinjiboonaaganan, gichi-mitigoon odayaawaajinigaanaan, waasa gaye odoondaawanaan, wii-zoongitood obiinjiboonaaganan. Mii dash gaa-giizhi’aad wiindamawaad ookomisan, mii dash e-naad, “Mii nookomis, gii-giizhi’ag biinjiboonaagan, mii dash giigoonh ji-amwad,” odinaan ookomisan.

“Eye,” ikido mindimooye.

And then truly did Nenabozhoo begin making his fish-traps, huge logs he carried on his shoulders, and from afar he carried them on his back, (for) he wanted to make his traps strong. And then after he had finished them he notified his grandmother, and this he said to her: “There, my grandmother, have I finished the fish-traps, and now some fish will you eat,” he (thus) said to his grandmother.

“Ay,” said the old woman.

From Nenabozhoo and the Fish Trap (William Jones, 1917, Ojibwa Texts, E.J. Brill, Ltd, Publishers and Printers Leyden, NY, p. 436 – 445, this story and all Anishinaabemowin words courtesy of Alan Corbiere, M’Chigeeng First Nation)

One fall day, two thousand years ago a young family left their home at Cahiagué near modern day Orillia to go to their ancestral fishing camp. This was a special place for them because they would meet up with their extended family and friends, many of whom they had not seen since the springtime. Once reunited, the men would travel the short distance to Mitche-kun-ing, the ancient fishing weir at the narrows where lakes Oentaron and Couchiching meet. The fishery was special too. It had always been there. The fish were called there, and if treated with respect, would offer themselves up to the nets. The women and the children would stay behind. Beginning with the first catch, the little ones amused themselves making toys and throwing bits of clay into the cool water as their mothers chatted and worked at cleaning and smoking the fish, or repairing the nets and generally preparing for the long winter ahead. Throughout all their activities they were careful not to throw any fish bones onto the fire as such an action was disrespectful and could jeopardize their next catch.

Moving 1600 years forward to another fall day, Samuel de Champlain visited Cahiagué, now the biggest of all the villages in the area, containing two hundred large lodges and surrounded by a wooden palisade. It is here, on September 1, 1615 that he and his entourage travelled to Mitche-kun-ing. Champlain recorded the fishing place in his diary and this disappointingly brief entry remains the earliest written account of the ancient weirs:

When the most part of our people were assembled, we set out from the village on the first day of September and passed along the shore of a small lake [Couchiching] distant from the said village three leagues, where they make great catches of fish which they preserve for the winter. There is another lake immediately adjoining [Lake Simcoe] which is twenty-six leagues in circumference, draining into the small one by a strait [the Narrows] where the great catch of fish takes place by means of a number of weirs which almost close the strait, leaving only small openings where they set their nets into the Freshwater Sea [Lake Huron].

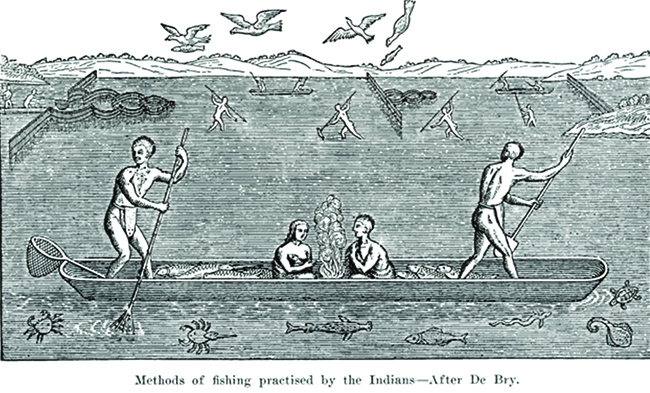

Although it escaped Champlain’s description, the French explorer would have noticed that bits of brush, twigs and wattle were woven between the stakes to create an impregnable fence. At the time of contact with Europeans, weirs and fish traps were the commonest forms of communal fisheries and when Champlain witnessed the one at Mitche-kun-ing, weirs had become the most efficient technique in indigenous fisheries. Here the fish were so plentiful that Champlain, with the help of the community was able to gather enough shigan [bass], kewis [herring] and maazhginoozhe [musky] within a little over a week to sustain an estimated 2,200 warriors for a planned raid into the interior against the Iroquois.

When the people of Cahiagué welcomed a wounded Champlain back in December 1615 no one would have anticipated that within a generation their thriving village would be disrupted by the trade wars with the Iroquois that swept across the lower Great Lakes area.

Following the Great Peace of 1701 held between the Anishinaabeg and the Haudenosaunee these ancient and rich fishing grounds were reinhabited by the former, who reestablished communities along ancient Lake Shining, called by the French Lac La Clie, (lake of the Hurdles or lake of the Fences)-and later by the English name Lake Simcoe. In 1917, Rama Elders recounting what they had been told about Mitche-kun-ing, or place of the fish fence, believed the site was ancient and it was their responsibility to maintain it. In fact, according to a recent oral history, Anishinaabe had learned about the weirs prior to the Beaver Wars. One Elder told Mark Douglas, a citizen of Chippewas of Rama First Nation:

As our people journeyed outward from the Great Falls, we discovered the Huron Nation fishing at the narrows. We spent considerable time with the Hurons learning all the techniques. We stayed long enough to gain the Huron’s trust and we were given gifts symbolizing our new relations…. [After several winters] the Anishinabek decided that we should continue to move westward seeking the place where the food grew on top of the water [wild rice].

In order to initiate the improvements necessary for the Trent Severn Waterway, a second channel running north of the original channel at the Narrows was dredged out in 1857. The best preserved of the ancient weirs can be found in the original channel which only has a depth of about two to three meters. Improvements to the marina and docks and an increased use of the area by sport fishermen led to further destruction.

Ironically, the threat of the weirs’ impending ruin sparked curiosity and interested parties were compelled to both undertake studies and to lobby for preservation. Archaeologist Walter Kenyon from the Royal Ontario Museum led the first archaeological investigation in 1966. Using SCUBA divers he attempted to plot out the stakes, which at the time appeared numerous. Unfortunately, his survey was discontinued and the project itself of limited use, but it did raise awareness of the site among non-Anishinaabeg communities.

In 1973, two archaeologists from Trent University, Richard B. Johnston and Kenneth A. Cassavoy conducted an underwater study of the remnants of the weirs, by now appearing as stubs sticking about an inch or two above the silty river bottom. They sent samples of a few of the stakes for radiocarbon testing. Cassaway hoped that the results would be old enough to link this site with the Champlain visit. He was unprepared for the news he received that one of the stakes dated back to 2610 BC, or roughly the same time that the Great Sphinx and the Great Pyramids at Giza were built.

Johnston and Cassavoy were also able to map out the remaining stakes and determine a rough pattern to their design. Ancient engineers planned the structure at a narrower, deeper section where the water was faster, located just outside of the bend of the original channel. At the bottom of the weirs they designed a rock path about 15 feet wide to stand on to enable the fishermen to place traps and nets across the weirs’ outlet at its north end without sinking into the mud. Studying the placement of the stakes the archeologists determined that one set of stakes was designed to catch fish swimming with the current towards warm and shallow Lake Couchiching while another set orientated on a diagonal in a northwest-southwest direction caught the fish which swam upstream toward colder and deeper Lake Simcoe. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the two weirs were built at the same time and repaired over the centuries, usually in the spring and fall. Tests also showed that the stakes were made from wood species including:

Wiigwaas [Paper birch]

Azhawemizh [Beech]

Niib [Elm]

Ninaatig [Maple]

Giizhig [White cedar]

Bwaayaak [White Ash]

Ookweminaatig [Black Cherry]

Maan’noons [Ironwood]

Johnston and Cassaway were able to map out a total of 535 stakes ranging in size from 1.5 to 3 inches in diameter, most being about 1.5 inches.

In 1982 the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs became a National Historic Site because of its unique historical and spiritual significance. These structures form the largest and best-preserved wooden fishing weirs known in Canada. Also, the site honours an ancient stewardship beginning thousands of years before the Huron-Wendat assumed the role, and continues on today with the Anishinaabeg. Moreover, it is considered a sacred place representing an ancient yet present spiritual bond between the Creator and all living things.

But in 1990’s the weirs came under a new threat. Increased motor traffic enroute to Casino Rama and further north into cottage country called for an expanded bridge along Highway 12. Mitigation archaeology was necessary because a large percentage of the better-preserved stakes could be found under this bridge and were therefore threatened. Led by Parks Canada archaeologists, an in situ examination was completed and then 137 stakes were removed for conservation and study. The controversial nature of this action together with the need for inter-community engagement led to the founding of the Mnjikaning Fish Fence Circle in 1993. Incorporated in 1996, the MFFC has a three-part mandate focusing on preservation, protection and education.

The Parks Canada excavation confirmed much of the findings and theories set out by Johnston and Cassavoy. It also arrived at an interesting discovery. Eleven of the sample stakes appeared to have been sharpened with an axe or some sort of modern metal tool. When submitted to radiocarbon testing these stakes were given a series of dates ranging from AD 1450 to 1615. In the words of a marine archeologist who worked on the site:

The dates present a problem when considered with the method used to sharpen the stakes. Although fitting within the Huron period, most of the dates are far too early to correspond to what is known about the introduction of metal tools in this area. It appears that, through some unknown phenomenon, the structure is dating to somewhat older than it should actually be.

After 4,000 years the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs still hasn’t given up all of its secrets.

Laurie LeClair has worked as an archaeologist, historian and technical writer for over 25 years. Since 2007 she has been a treaty researcher for Union of Ontario Indians and is also a regular contributor to Anishinabek News. She lives with her husband and son in Toronto.