Keeping Indians out of pool halls a Canadian priority

By Maurice Switzer

By Maurice Switzer

As to why Indigenous peoples won’t be out in droves to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday party, it’s amazing there isn’t actually a provision in the Indian Act to prohibit such a thing. The legislation first enacted in 1876 was littered with bans on activities like singing, dancing, and participating in public events in “Aboriginal costume”.

If Canadians see any pow-wow dancers on the Parliament Hill stage during the July 1st festivities, they should be aware that such uncivilized behaviour could have landed them in jail less than a century ago.

The Indian Act has enforced some bizarre stipulations over the years.

• In 1869, Canada adopts a formal policy of assimilation of Indians, the end goal being the eradication of all Indigenous traditions, customs, and beliefs. The 1857 Gradual Civilization Act morphs into the Gradual Enfranchisement Act, and then into the Indian Act, which forces bands – sometimes at gunpoint – to adopt municipal-style councils. Ottawa unilaterally imposes three-year terms of office, and determines every aspect of the political structure, including the number of council members and the removal of elected chiefs by federal authorities for what they deemed to be “dishonesty, intemperance, or immorality.” Women, who in many Indigenous cultures have played a key role in selection of community leaders, are not allowed to vote in band elections until 1951.

•The federal government constantly tinkers with what it terms “enfranchisement”, whereby Indians give up their status rights and obtain the same voting rights as Canadian citizens. At one point anyone leaving the reserve for an extended period of time — for example, to pursue higher education — will automatically be stripped of their Indian status and rights.

• In 1874, Indians found to be intoxicated on or off-reserve can serve a month in jail, and an additional 14 days for refusing to identify the seller.

• A key goal of the federal assimilation policy has been to turn the Indians into farmers, the European concept of how “civilized” folks function. In 1881 Indians are prohibited from selling their agricultural produce without permission, after non-Indian farmers complain about what they see as unfair competition.

• In 1884 the act outlaws the potlatch, a ceremony of traditional songs, dance, feasting, and sharing personal wealth that has been practised for centuries by West Coast tribes. These events offend Christian missionaries, and threaten jail terms of up to six months for transgressors. In 1904 a 90-year-old nearly-blind man named Taytapasahsung serves two months at hard labour for dancing. Notorious Superintendent-general Duncan Campbell Scott issues a famous memo to Indian agents across the country urging them to “discourage these dances…as they take the Indians from their work.”

• The same year the act attempts to ban free public assembly on reserves, making it an offence to incite “three or more Indians or halfbreeds” to breach the peace or to make “threatening demands” on a civil servant, that is, the Indian agents who rule reserves with an iron fist. Authorities can prevent the sale of ammunition to reserve residents they regard as malcontents, a drastic penalty for people who hunt to put food on the table.

• The pass system is introduced in 1885. Indians can only leave their reserve with written permission of the Indian agent. Officials from South Africa’s apartheid regime will visit Canada to study the system, which they eventually adapt into their own racist model.

• In 1894 Indian band councils are stripped of the right to decide whether non-Indians can reside on or use reserve lands, and Indian agents sometimes start leasing reserve lands to outside business interests in exchange for personal financial gain.

• In 1911 the act is amended to allow judges to move reserves adjacent to non-Native communities if it is deemed “expedient” to do so, in other words, to free up urban land for commercial development. In 1915 a Mi’kmaq reserve in Sydney, Nova Scotia is relocated because a local judge decrees that “removal would make the property in that neighbourhood more valuable for assessment.”

• In 1927 Indians are forbidden from retaining lawyers to pursue land claims or other legal matters, one reason why there are 1300 outstanding land claims today. This Indian Act provision remains in place until 1951.

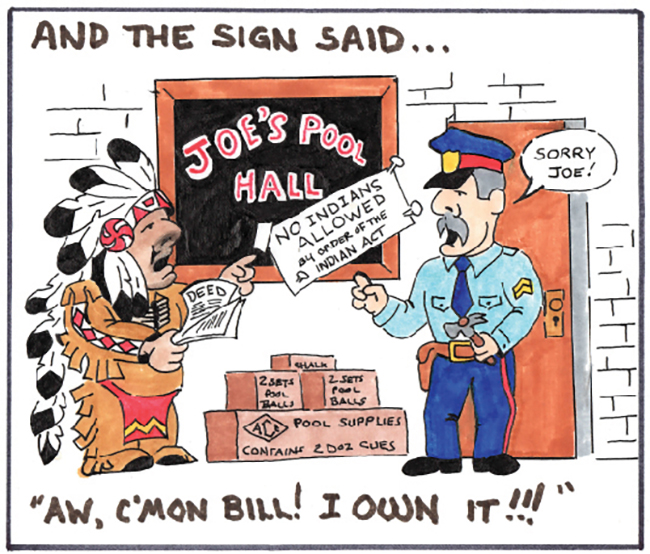

• In 1930 it becomes an offence for a pool room owner or operator to allow an Indian onto their premises. The penalty is a fine or a one-month jail term. The Indian Act provision claims that by “inordinate frequenting of a pool room either on or off an Indian reserve”, an Indian “….misspends or wastes his time or means to the detriment of himself, his family, or his household.”

*********

By far the most sinister aspects of the Indian Act are those still in place that dictate in precise terms exactly who has Indian Status, a matter strictly under the control of the presiding federal minister of Indian, Aboriginal, or Indigenous affairs.

These provisions have always discriminated against Indigenous women, who, before a 1985 amendment, could lose their status by marrying a non-Native man, while a non-Native woman could acquire status for herself and her children by marrying an Indian.

Under pressure from international human rights agencies and several Supreme Court decisions, Canada has reluctantly amended the Indian Act’s status rules, but they still legislate expiry dates on Indigenous citizenship.

This makes Canada’s Indian Act the only piece of government legislation in the world that regulates an individual’s heritage.

It is also a legislative means of committing genocide – defined as “the deliberate killing of a large group of people, especially those of a particular ethnic group or nation.” If Canada were to be allowed to continue imposing its Indian Act status provisions, it is conceivable that they will disappear, due to the inevitable intermarriage of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

This is why some Haudenosaunee communities have resorted to evicting community members who “marry out”. They claim to be exercising the same cultural-protection measures as the province of Quebec did by implementing its controversial French-language laws.

In carrying out Canada’s official policy of assimilating Indians, Duncan Campbell Scott’s stated objective was “to kill the Indian in the child.”

As it now stands, the Indian Act’s inevitable outcome would simply be to kill the Indians, period.

No thanks, Canada. You’ll have to party on without us on July 1st. When you don’t see any Indians there, you can just pretend that the Indian Act succeeded.

Maurice Switzer is a citizen of the Mississaugas of Alderville First Nation. He lives in North Bay, where he operates Nimkii Communications, a public education practice with a focus on the treaty relationship between First Nations and Canada.