Chief Rogers hopes to get more data on pollution-related illnesses

By Colin Graf

AAMJIWNAANG – Chief Joanne Rogers is beginning to feel hope for the future health of her people, surrounded by more than 50 petrochemical plants and refineries in “Canada’s Chemical Valley” near Sarnia. In recent weeks, prompted by concerns from the community and media reports on air pollution in the area, the provincial government has announced a series of new control measures. While Chief Rogers is encouraged the province is finally taking air pollution problems seriously, she is still expecting more effort to find out if residents are suffering excessive levels of pollution-related illness.

Rogers says Aamjiwnaang’s Environment Department and Committee are currently reviewing the proposed changes to regulations regarding the chemical sulphur dioxide, along with a proposal from Ontario’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) for a new approach that would consider the cumulative effects of air pollution from industries that that emit the chemical benzene, a known carcinogen.

“Our environment committee along with our community have lobbied hard to ensure improved air quality in our community for our members. Our expert is currently working with the MOECC to ensure Aamjiwnaang’s concerns are being met and included in the new regulation,” says Chief Rogers.

The First Nation is also welcoming a decision by Minister Chris Ballard to help fund a study of health problems in the area, but fears persist the study won’t create enough data to understand the health problems at Aamjiwnaang. Chief Rogers is concerned about ensuring the study will focus “on our community” rather than just the greater Sarnia area. The fear is that statistics from the First Nation will be “diluted” among results from the larger population, according to Sara Plain, director of the Aamjiwnaang Health Centre.

While not promising a separate health study for Aamjiwnaang, a statement by Ballard says the project will help people “better understand the impact of pollution on First Nation communities and Sarnia-area residents.”

Plain hopes the coming study will finally provide clarity on whether industrial emissions can be linked to illness. ”We need a very clear picture of the health issues that community members are facing…with a clear correlation to industry or other causes.”

“The First Nation and nearby municipalities have been trying to secure government funding for a health study since 2007 without luck,” says Plain. “Local industries have pledged to pay a third of the cost of a study, but senior governments have made no commitments until now.”

Janet Fawcett, an Aamjiwnaang citizen living in Sarnia, is glad to know the study will finally take place. She fears she is facing her second battle with kidney cancer. Fawcett has also lost two sisters to different forms of the disease, and her mother is on her “third round”. “I’m terrified of cancer, and now they (doctors) think it’s back,” said Fawcett, one of ten children.

She hopes any information discovered by the proposed health study will help future generations. “I think it’s a good thing because there’s a lot of young ones and I want to protect them, my grandchildren,” she said.

Aamjiwnaang’s people are not just waiting for the health effects study. They are also taking their own steps to find out if widespread fears of elevated cancer rates are grounded in reality.

Health Centre workers are teaming up with Cancer Care Ontario (CCO) in an effort to comb through 20 years of data in hopes of providing information to help compare the health of Aamjiwnaang residents in the past to results of the upcoming study.

The compiling of past data, to be completed next March, will cover much more than just cancer diagnoses, says Plain. The community has health concerns that stretch much further, she explains.

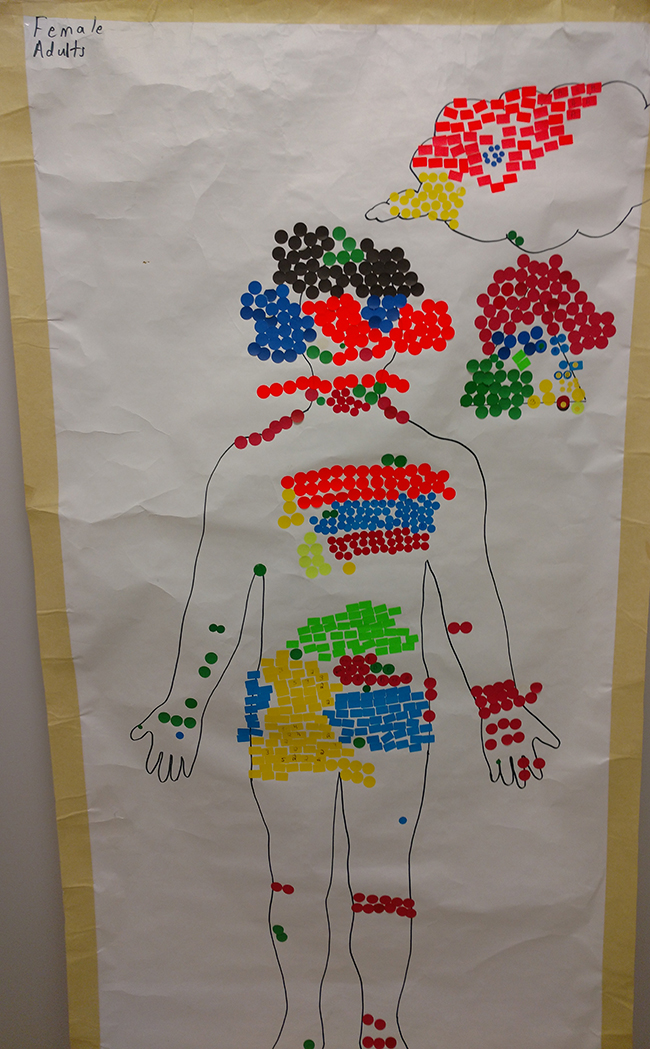

A survey at Aamjiwnaang about 10 years ago found diagnoses of many different health concerns, from respiratory problems such as asthma to learning disabilities, to skin problems, according to Plain. ”Just about every woman will tell you stories about high numbers of miscarriages,” she says.

“It’s important to go back over the past data,” said CCO epidemiologist Amanda Sheppard at a recent community meeting at Aamjiwnaang. “The information doesn’t always get back to the community,” she said. “Folks don’t often see the recommendations or conclusions from those studies.”

One past study sparked significant concern in 2005, when an environmental journal found the ratio of male to female births in Aamjiwnaang was two girls for every boy instead of the normal one-to-one ratio from 1999-2003. An update on that study is expected before the end of this year, according to Plain.

Working on these studies has led to hearing a lot of “overwhelming” stories about families dealing with cancer, said Plain.

Janet Fawcett’s story is one of them. Growing up in Sarnia, a few Kilometres away from the First Nation territory, she and her sisters often visited family there. Her brothers, who have not developed cancer, moved to Ottawa years ago. Cancer is a common topic of conversation in the area, Fawcett said. “We have too many women with breast cancer down here. We just had another one last week,” she added.

“There are people in our community with cancer fighting for their lives right now. I don’t need a health study to convince me, but the people want that confirmation,” Chief Rogers said.

She has received support for her worries about air pollution from Ontario’s environmental watchdog. The annual report by Environmental Commissioner Diane Saxe, released recently, said Aamjiwnaang “suffers some of the worst air pollution in the country,” with industries releasing millions of kilograms of pollution into the air yearly, Saxe said there is “strong evidence” the pollution is causing adverse health effects, which neither federal nor provincial governments have properly investigated.

Saxe has also called on the province to update its air pollution standards, improve its capacity to respond to environmental incidents in Sarnia, invest in stronger monitoring and enforcement, and improve communication with the Aamjiwnaang community.

Ballard said he agrees with Commissioner Saxe that more needs to be done to support indigenous communities, and he will “take action” on the cumulative effects of pollution in heavily industrialized areas of Ontario, such as Sarnia.

Aamjiwnaang councillor John Adams worked for many years at a local refinery before retirement, and has seen a lot of cancer. He would like to see cancer screening offered to his community just as it was offered regularly to him when he worked in the plants. “It was a great thing when I worked. I was being tested all the time,” Adams, told if his blood tests showed a risky reading, “I was taken out of that unit and not allowed back.” Adams has continued that routine into retirement, getting the same tests through his family doctor. “After all, I live right next to Suncor. It’s just like being at work.”

However, Adams knows many in his community aren’t getting that kind of medical attention, “so they slip through the cracks.” He hopes some kind of voluntary blood screening can one day be offered to everyone at Aamjiwnaang.

Local industries say they are working to make improvements. Companies have been monitoring the air in the Sarnia area for 65 years. There has been “a trend of consistent improvement over 10 years,” according to a public letter to media from Dean Edwardson, General Manager of the Sarnia-Lambton Environmental Association, a Sarnia-area industry group, whose members include such companies as Suncor Energy, Shell Canada, Nova Chemicals, and Imperial Oil.