A tribute to Gazh Gad Nang – Mid-Day Star – George Charles: Caring catalyst for inclusiveness and reconciliation

Submitted by Yvonne Germaine Dufault

This 2017 reconciliation reflection arrives on time for Christmas in the spirit of “Peace to all”, in memory of Elder Gahz Gad Nang [Mid-Day Star] who died on Dec 23, 2003, exactly fourteen years ago, only two months after he was publicly recognized on stage for his significant contributions to character education. In small and large groups he interacted with students at two elementary and two secondary schools where I taught and at scores of others.

Gahz Gad Nang, an Ojibway man known to many by his English name, George Charles, visited my intermediate students at Doncrest P.S. in Richmond Hill in 1995. For our November 11, 1996 Remembrance Day event at William Berczy Public School in Unionville, he accepted to be our first Anisihnaabe Korean war veteran speaker, driving for two hours in inclement weather to Unionville to keep that promise. Junior kindergarten to grade eight students and their teachers sat around him, right on the gymnasium floor. Without a microphone, in a clear soft-spoken voice, he uplifted our entire school population. We listened intently, silently, deeply moved, feeling like our hearts beat as one. No one even coughed. Anyone with hurt or angry feelings breathed in gentle words flowing freely through George. You could have heard a pin drop as he stated that each and every one of us is worth caring about: “The Creator don’t make no junk. There is nobody less than you. There is nobody more than you. We are all equal in the eyes of the Creator.” When I later presented George Charles with a modest honorarium, he said: “My tank was on empty. I hawked the ring my niece from B.C. gave me to pay for the gas. On my way home, the first thing I am going to do is get it back from the pawn shop. This means a lot to me. Meegwetch.”

Extending his hand in trust, friendship and acceptance from the onset, when he met a person, Mid-Day Star was fully present, listening with his eyes, ears and heart. He welcomed people from all races, religions, backgrounds and walks of life. He walked in faith. He believed the Creator, “the God of your understanding” would provide for our basic needs, not testing us beyond what we could bear. With permission, George prayed alongside people asking the Creator to help them move through their pain to a more peaceful place. Once when I was going into anaphylactic shock, far away from medical aid, George prayed over me and the symptoms just faded away. George walked in faith and trust at a time in human history when worldwide, even now, control though fear is privileged by people in power as a major motivator in workplaces, school systems and societies in general. People who fear repercussions are less likely to tell the truth. Like my father, Mid-Day Star believed a child should never be punished for having the courage to tell the truth when a mistake was made. The natural consequences of a sideways action were enough to remember the lesson.

When did I meet Ojibway Gahz Gad Nang [Mid-day Star] for the first time? It was the last Saturday in October, 1993. My group was participating in the third annual themed teaching Pow Wow organized by the Chippewas of Georgina Island, held in Sutton District High School’s gymnasium. Having spent most of his life in a white world after being removed from his Native community in Rama at age two, Mid-Day Star reclaimed his roots. He took pride as he learned more about his culture and his heritage along the Pow Wow trail, following a Pow Wow calendar. I watched him in the Grand Entry which was the opening dance performed by First Nations, Inuit and Métis war veterans, after which the Eagle staffs were posted.

As a promoter of proactive race relations, I had choreographed line dances for my group of student community service volunteers known as Dancers for Harmony. Mid-Day Star’s first words to us as together we circled the big drums clockwise during an intertribal dance in our personalized regalia were: “This is the first time that we have all the colours of the medicine wheel here. Now the circle is complete.” Looking around, I realized my students were white, yellow and black. A brown child asked where her place would be on the medicine wheel. We danced joyfully with this welcoming red man who believed youths from all peoples cooperating as one human tribe could achieve world peace. We discussed the Hopi Medicine Wheel Prophecy:[1]

Unknown to me at that time, the Lakota Medicine Wheel symbol, which looks the same, would become part of my shared thesis journey with Gahz Gad Nang and its teachings the spinal core of my own life moving forward.

October, 1993 was my students’ second indoor Pow Wow experience. Our first outdoor one had been on Georgina Island during a secondary school teachers’ strike. In 1991, during lunch for presenters at a Race Relations conference, I had met Nimkie Benishie-Nini (Thunderbird Man) of Mnjikaning First Nation (Rama) known to many as Harvey Anderson. To him I would posthumously dedicate my U of T 2003 thesis on First Nations character education[2]. I was unaware at the time that his friend Mid-Day Star would also enter my life with dramatic positive impact, influencing hundreds of our elementary and secondary school students, becoming one of five people I would interview in 2001.

Anishinabek people of different groups and clans came to York Region District School Board’s annual teaching Pow Wow from faraway places to celebrate, communicate and contribute their talents, crafts, foods, songs and stories. We learned dances like the friendship dance. In 2003, my Dancers for Harmony group stayed until the very end of the evening to participate in the closing intertribal dance with Mid-Day Star. Dancers each got to select a gift from ‘sharing blanket’ as they circled clockwise around the great drum. Pow Wows, like Potlatches were once outlawed by the Canadian government. We never imagined that the 1993 Pow Wow at Sutton District High School would be the first of many Pow Wows across Ontario with Gahz Gad Nang, known to most people by his non-Native name George Charles which was easier for non-Native newcomers to say and remember .

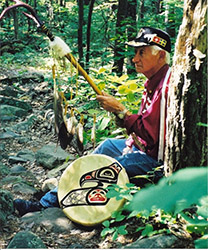

George Charles interacted authentically with people in a wide variety of settings that included A.A, Pow Wows, classrooms, outdoors and institutions in Barrie and Campbellford. He stressed traditional teachings of inclusivity and interconnectedness within the web of life. Mid-Day Star had no post-secondary ‘paper’ degrees to substantiate his education in the eyes of academia of the dominant colonizing culture. He worked hard at a blue collar job in the manufacturing industry to provide for his family. His main education arose from the school of life, practical and largely informal. George said he learned a lot from listening to others, especially interacting with the children. He valued oral tradition and hands on experience. He used storytelling and poetry as powerful tools for guiding understanding and decision-making. Since 2006, narrative forms of thesis work have become more widely accepted at the doctoral level in Canadian universities.

George Charles became like an extended member of my family during a decade extending from our first October 1993 encounter until his death on Dec. 23, 2003. He encouraged my daughter of mixed blood, who explored her Abanaki roots on both branches of her father’s family tree in Quebec.

During the ten years that our family got to know Gahz Gad Nang, he modelled embracing the Good Red Road in thought, word and deed as he completed an overlapping decade of inclusiveness. 2003 to 2013 was identified by the United Nations as the “Third Decade to Combat Racism and Discrimination.” 1994 to 2004 was the “International Decade of the World’s Indigenous people”. [3] George Charles invited recently-arrived non-Native newcomers from all over the globe and all walks of life to join him dancing in joyful gratitude on the Pow Wow trail. George had faith that human beings are basically seekers of truth and goodness. Generous with his time, he invited peoples of differing world views to dance in the Sacred Circle. He gifted to people what he could. Over the years, I was happy to ‘pay it forward’ , to be part of the process of providing George with sinew, skins and various materials for making crafts and drums with which inmates at Warkworth could purchase some of life’s little comforts like smokes. George even invited me to a sweat lodge at Warkworth where he served as an Elder and where my Windhorse Drum and a beautiful feather box I commissioned had been mindfully dreamed into existence and consciously created by talented artists equally invested in their own healing. Although I didn’t attend, I appreciated the invitation. Gahz Gad Nang engaged in hopeful face to face, heart to heart dialogues that made individuals contemplate what really mattered in their lives. Many laid down their burdens with offerings of sema [prayer tobacco] at the Sacred Fire, asking the Creator for guidance.

Hundreds of people travelled long distances to pay their last respects at the funeral home in Cobourg on December 23, 2003. The list of signatures in the Guest Book quickly grew. There were so many of us, we couldn’t all fit inside. A long lineup waited their turn outside. Visitors told each other stories about how George had improved their lives. A History teacher named Eugene Nikolov who had immigrated from Bulgaria to Canada in 1995 and attended George’s funeral recently shared this quote with me:

“I first saw George at a pow-wow on Manitoulin Island 20 years ago. He was carrying the eagle staff at Grand entry. He was wearing his medals and Army beret. I instantly felt deepest respect for him. I was nobody at the time and I did not dare speak to him. He had this aura around him of a warrior and elder. A few years later I saw him at another pow-wow, a small event in Algonquin Park. It was a smaller traditional pow-wow. When we got to talk, I realized the kind and gentle person he was. He read a poem he had written. Although I no longer remember the words, I still remember the feeling and his message of love and caring. I was surprised by how he was talking to me, a stranger, like he knew me for a long time. This evening, after talking to him by the fire, my girlfriend and I participated in a spot dance. She won a beautiful eagle necklace. I still think to this day that this was not a coincidence.”

I’m sure Eugene married that girl. Another man moved by the Elder’s generosity of spirit, Zhaashid Mkinnaac [Richard Charrette] said of him:

Mid-Day Star is a truly great man, whose presence and spirit brings a calmness to whomever he comes in contact with. His soothing way that he helps to respectfully heal one’s spirit is an experience that we will never forget. Everyone who crosses his path knows that they have just met a very special person who cares about life. He devoted his life to the betterment of the human race.

I met Mid-Day Star in 1998. My life was changed forever. I have never met such a caring and loving person in my life. Mid-Day Star became my Elder for the next 5 years. He taught me how to forgive, love and respect myself, as my healing journey never ends. I will always remember and respect the teaching that I have received from him. He showed me a better way to live life to the fullest. Mid-Day Star was my Elder first but he became one of my closest friends. I miss my friend but I know he will still be with me forever as his spirit is imprinted in my soul. Be free my friend, Respect and admiration,

Many of us recognized George as a rainbow bridge who helped people make meaningful connections . Posthumously, on November 21, 2004, a speaker on APTN network declared George Charles [Mid-Day Star] who was buried eleven months earlier, among Canada’s top 14 aboriginal heroes. This informal facilitator was recognized for fostering peace among peoples. With a foot in two worlds, Mid-Day Star stressed we are all members of the global human tribe. The Original Peoples of this land are our brothers and sisters.

The word ‘hero’ typically conjures up images of a battlefield. A hero can be gentle. Active on the Pow Wow trail, taken away from Mnjikaning First Nation when he was two years old, Mid-Day Star was a peacemaker. He enjoyed lightweight boxing in his youth. He loved to laugh and dance. He raised a family in a white world that accepted him, that he had known most of his life. He did not see non-Native people as the enemy. In his later years, George actively sought out and reclaimed his culture. He was proud to carry his Eagle staff at the Grand Entry, happy to be Anishnabe. He didn’t judge anyone by physical appearance or past mistakes. George welcomed everyone into his heart. He taught youths from all colours, creeds and backgrounds about the sacredness of life, the Seven Grandfather teachings, the Good Red Road, the importance of harmony and balance and teachings of the Medicine Wheel. He helped people of differing worldviews understand each others’ perspectives or at least agree to disagree amicably.

George Charles talked the walk, but also walked the talk. He wasn’t one of those ‘do as I say, not as I do’ people. He was a Christian who trusted others, a good Samaritan who helped when he could. He saw the goodness and potential in everyone. No matter how hard, he never gave up on people.

I attended his funeral service with philanthropist Valerie Campbell, a “beautiful woman” he had met on the Pow Wow trail, whom I had never met before, but who he had very much wanted me to meet. She wrote:

“George Charles shone brightly in my life. A friend, he gave himself unconditionally. A teacher, he shared traditional teachings. A mentor, he opened my life to new ways of looking at life. As Mid-Day Star, one of George’s many gifts was lighting up any room and any group of people! It was amazing how his presence and his words enabled people to discover their talents, abilities, and passions. It was as though he could light the way for people to make important self-discoveries. George remains with me to this day through his words and poetry. One of his passions was writing. I continue to read his meaningful words, and they light me up. I shall always be grateful that universe saw fit for our paths to cross. Meegwetch.”

At Mid-Day Star’s funeral, I met people from all walks of life to whom he had given encouragement and hope that they had the power to get their lives back on track. George Charles helped both students and adults understand that resentment is a poison that lives rent free inside our head if we let it, gnawing away at the health of our mind, body and spirit.

At the funeral home, when it was my turn to sign the guest book, I wanted so much to ask other mourners who came to pay their respects to write one line each about how George had impacted their lives in that guest book, but that was not my place. In retrospect, fourteen years later, I know that if I had asked the family about this, the answer would have said ‘yes’ and others’ thoughts could have been added to a special scrapbook George’s youngest daughter later put together about her father’s life.

George gave of himself to so many people, but always made time for family, stressing the importance of building strong family ties. Family outlasts careers. Family forgives. Family endures. Family loves.

On November 23, 2017, Mid-Day Star’s granddaughter Jocelyn, daughter of Mitzi wrote:

I am grateful to be able to say that from a very young age, I knew I could count on my grandfather for pretty near anything. Perhaps many children feel this way about one or more of their grandparents. However, the older I got and the more I learned about him, the more I understood that he was someone very rare and special in this world. By the time I entered my teenage years, that sense of trust and security I felt for him as a granddaughter had developed into a more mature appreciation that I was lucky enough to have a person like George Charles in my life. I am 30 now. Since his passing, I have experienced much joy and accomplishment, but also many hardships. The more experiences I have, the more I long for one more conversation with my grandfather. I am old enough to really embrace all that he was. Even though he is gone, I still look to him for answers. I often find myself reflecting or meditating on his words when I am in despair and I try my best to model my life after the values that he instilled in me. My grandfather is very much alive in my heart and there he will stay until we meet again.

On the same day, granddaughter Carrie Ann Martin, daughter of George’s son Mike wrote:

Sometimes it’s the small things that become the most significant and important memories. When I was young, I could always count on finding my Grandfather at Church on Sundays. It didn’t matter who he was chatting with after the service, he would take a moment, pull me aside, give me a handshake and that’s when he would sneak into my hand a cert mind and a few bucks. Although I did love the sweet taste of the cert mints and could always find something to do with the change, it was in those moments that I felt his love for me. The last time I was with him was at what turned out to be his final speaking engagement with my grade ten class. Before he hugged me goodbye that day, he shook my hand and snuck me a ten dollar bill. A final reminder of his love.

I remember being on Manitoulin Island with George, in 1994, who was placed in charge of supervising an Ojibway girl and boy while their parents worked. They wanted to go swimming. The water would refreshing for the children after a hot day of Pow Wow dancing in the sun at Wikemikong. As I parked the car, sensing broken bottles, I cautioned everyone to be careful getting out. There were shards of glass scattered about on the land but none into water. Water up to her waist, the girl started singing in a beautiful voice “What is God was one of us? Just a stranger on the bus…” as Great Blue Heron blue soared overhead. George said it was a bird of spirit. We were fully present in the moment. It was magical.

On October 10, 2003, unlike the others who were presented with received an Eagle feather from Honorable James K Bartleman, George Charles received a slightly longer feather of a slightly different shade. No one noticed it right away. In November George identified it as coming from the Blue Heron, a bird of spirit connected with Spirit World and life on the other side. On December 23, 2003, George was the first of the four elders to pass away. The third passed away on January 1, 2017. Now only the youngest Elder who lives on Birch Island remains still walking on Mother Earth.

George was a man of modest of means who shared what he could with others. He filled our buckets with feelings of connectedness, hope and goodwill. He reminded us of the importance of forgiveness and reconciliation. Ojibway MidDay Star of Cobourg left this world first in 2003, Inuit Susie Nakoolak of Rama (widow of Harvey Anderson, mother of Karen Campbell) died in 2014. Most recently Haudenosaunee Kahskennontora:ken of Ohseweken(Whitedeer), wife of Iroquois historian William Guy Spittal) passed away on January 1, 2017. If they were still alive, these three Elders, all from different clans, descended different Original Peoples of Turtle Island, I am sure they would all reinforce this message: Forgiving others and oneself is not enough. We must ask those against whom we have hurt in any way to forgive us in turn, even if that hurt was unintentional. That is key to reconciliation under the Tree of Peace.[4] Ojibway Elder Gloria Oshkabewisens-MacGregor of Birch Island and Ojibway playwright Drew Hayden Taylor of Curve Lake First Nations whose timely plays like Spirit Horse[5] tour the schools are still here in the physical to help guide us to our own answers and strengths within. We cannot undo the past, but like Mid-Day Star often quoted to my students: “Yesterday is history. Tomorrow is a mystery. Today is a gift. That is why we call it the present.” The gift that such wisdomkeepers leave behind that is a crucial part of the Seven Generation legacy is their stories. George’s stories and poems, a gift of loving spirit, along those four others can be downloaded from Collections Canada: www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk4/etd/MQ84211.PDF

Our greatest legacies are the loving memories we leave behind in the hearts and spirits of others. In 2017 as part of my own reconciliation, I forgave others and myself. That was not enough. In 2018, I will ask those whom I know have offended in any way to forgive me for what I have done, and what I have failed to do. I believe we are Spirits who come into a variety of human forms here on Mother Earth to learn what means to truly be ‘human’. I also believe that moving in the direction of being more aware caring humane BEing rather than just a busy human DOing is our journey. My ancestors came to Canada between the two world wars. I was born into the Roman Catholic Church. Personally, I come from very gentle people. I myself am gentle. On behalf of the dominant colonizing cultures, know that I am sad that my church and the Anglican church did so much damage to children with the residential schools. I am so very sorry. I ask for your forgiveness. We must value all our sacred children. May we walk in beauty together.

The Mid-Day Star award established in 2004 School in memory of George Charles, with help from my then Junior Octagon Club presidents at Pierre Elliott Trudeau High. We recognized service to the people –inclusiveness, compassion, acceptance and appreciation of the Original Peoples of this land. Mid-Day star’s stories, like those of the others in the 2003 thesis work which we put our minds together to complete, continue to help the next seven generations in countries around the globe. Among earlier recipients was Margaret Aldridge, a genealogist who passed away in August, 2012. As a volunteer, she helped individuals who were part of the stolen generation, who had been taken away to residential schools find their families and regain their Native status. In 2018, as I continue my journey with my New Year’s Resolution, I will share stories about the recipients of this award.

[1] http://www.maitreya.org/english/Newsbrief/2011/1-January-February/Articles/Hopi-Medicine-Wheel.html

[2] http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/s4/f2/dsk4/etd/MQ84211.PDF A QUEST FOR CHARACTER: EXPLAINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FIRST NATIONS TEACHINGS AND “CHARACTER EDUCATION

[3] http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/48/163

[4] http://www.goodminds.com/white-roots-peace-iroqrafts-paper-ed

White Roots of Peace, reprinted in 1998, is an important contribution to the understanding and significance of the Six Nations Iroquois / Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace originally published in 1946. Paul Wallace wrote this popular account of the founding of the Great Law of Peace. He set out to provide the general reader with a greater understanding of the message of peace brought to five warring nations by the Peacemaker. While researching the Iroquois, Wallace made several visits to Six Nations of the Grand River where he met with Jake Hess, Joseph Montour, and Chief William D. Loft. These personal interviews combined with the Great Law texts, previously published in translation, provided Wallace with the necessary background for a composite narrative. In addition to the original Wallace narrative, this reprint contains new material that adds a greater insight about the author and how the 1946 publication came to be written. Editor William Guy Spittal has included 14 archival photographs, 11 illustrations by Wilfred Chew Jr., an introductory essay by historian Donald B. Smith from the University of Calgary, and six published reviews from 1946. This book brings the message of peace, first given to the Haudenosaunee centuries ago, to a worldwide audience. That message of peace remains vital in today’s conflict-driven world. Recommended for anyone interested in the Iroquois, peace studies, history, and Native American Studies.

[5] http://www.drewhaydentaylor.com/produced-plays/