Two artists, one message

By Barb Nahwegahbow

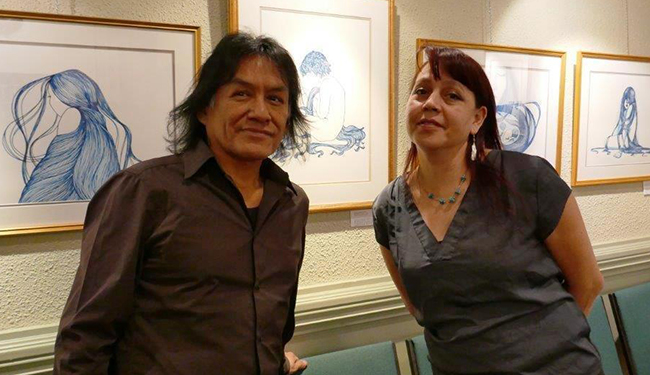

TORONTO – Two Anishinawbe artists had a very successful showing of their work last month at the First Unitarian Congregation Art Gallery at Avenue Road and St. Clair.

Joseph Sagaj and Keitha Keeshig-Tobias were the featured artists of an exhibition titled, Presence: Me-Ho-Mah Nong-Gohm – Here and Now. It opened on December 10th. Sagaj is a member of Neskantaga First Nation, and Keeshig-Tobias comes from Neyaashiinigmiing Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation and the Delaware Nation at Moraviantown. Both are currently based in Toronto.

Keeshig-Tobias took a break from her art to raise her children, and she’s happy to be back into it. This was her first big show, she said, but it’s just the beginning. She draws with dipped pen and ink and most often uses blue ink. “The colour resonates with me,” she said, “it’s twilight, it’s a time of change, night to day, morning to night. I also like the deep blue water of Georgian Bay, the waters and the rivers.”

There aren’t too many people who use pen and ink, said Keeshig-Tobias, “and there’s no one who uses it the way I do.” It’s a detailed process with several layers of ink that takes a lot of time and care.

Among the pieces she had in the exhibition was a series of five drawings about residential school. She uses hair in the drawings to depict feelings, ideas and thoughts and, “because hair happens to be very important in our lives and I like drawing it,” she explained. They are skillfully executed in her trademark style and with simple lines and multiple layers of ink, Keeshig-Tobias conveys a whole host of emotions – grief, loss, pain, confusion – that left many viewers visibly moved. Perhaps the most poignant of the five drawings is the middle one –a naked child, their back to us, head bent, their hair in ruins around them. She’s taken us into the heart and spirit of the child and the devastating impact of residential school.

I enjoyed seeing that my work moves people, said Keeshig-Tobias. “Many of them are very moving when I’m doing them and sometimes I have to stop and take a breath and make sure I don’t get too emotional, I don’t want tears falling on the picture.”

The fifth and final piece in the series is called, Sitting with the Feelings. That is something we all have to do, she said, recognize what has happened and what it does to us. She acknowledged it’s not an easy process, “but there is no other way forward except to sit there with feelings and recognize what it does to you.”

The Seven Stages of Life teachings done in the Woodland school style constituted part of the work shown by Joseph Sagaj. This work was commissioned by the provincial Ministry of the Attorney General (MAG), he told the audience in his artist talk. Prints were on view at the exhibition as the originals reside in the MAG offices on Bay Street.

Sagaj’s work is complex, bold and colourful and contains many doorways into the worldview of the Anishinabek. The paintings are also a mirror in which the Anishinabek can see their reflection. The pieces are skillfully rendered and reminiscent of his childhood artistic hero, Norval Morrisseau. It’s Sagaj’s interpretation of the Anishinabek seven life stages teaching that he’s learned from elders including Jim Dumont, Jackie Lavalley and Dorothy Pitawanakwat. The stages go from birth when the new spirit enters the world to the final stage of life when the elder looks back at their footprints to see what they’ve done for the people. Sagaj has also included the Seven Grandfather teachings and clan symbols in the paintings.

Sagaj shared his personal experiences with the audience, from his time at Residential School, to contemplating suicide like many Indigenous youth today, to time spent in jail. “Today, I speak my story,” he said, “I share my culture, I speak my language and I’m not afraid. Today, I’m connecting to my culture and I’m proud of that.”

Sagaj talked about the Northern Lights Collective, a volunteer group of artists who have come together to support Northern youth with donations of sports equipment and art supplies. His dream is to run an arts camp in his community of Neskantaga for northern Indigenous youth. The Collective is seeking donations that can be sent to the communities, he said.

The curator of the exhibition, Kate Cottington said, “Both artists, with their very different approaches, helped us to better understand their lives and their worldview. Through their authentic voices, they told their stories. Their words – both at the morning service and at the art opening reception – moved us all profoundly.”

The congregation, Cottington said, wants to support the initiatives of the Northern Lights Collective. One of their members has offered hockey equipment and their arts committee will be collecting art supplies. The work of both artists and Joseph’s call for ‘reconciliaction’ has inspired us all, she said.