Robertson awarded Order of Ontario

By Colin Graf

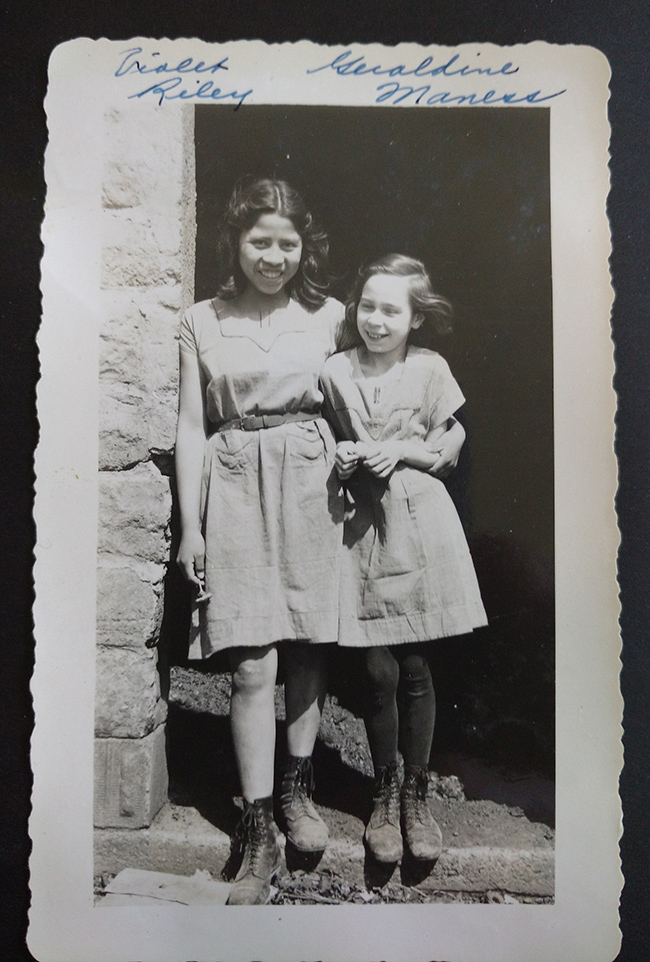

AAMJIWNAANG FIRST NATION – Elder Geraldine Robertson, 82, has been awarded the Order of Ontario for her work in educating people across the province about the experiences of First Nations people in the residential school system.

Robertson has spent much of the last 20 years speaking about her experiences from Ontario to British Columbia, most commonly with the support of the United Church, telling her story and encouraging other residential school survivors to talk about their experiences.

Her citation from the government describes Robertson as “an educator and advocate for residential school survivors” who has encouraged other survivors “to open up and strive toward healing, educated countless people on the intergenerational legacy of residential schools, and helped advocate for compensation for survivors.

Robertson was nominated by members of the Huron Shores United Church in Grand Bend, headed by Rev. Kate Crawford. She and her parishioners decided to submit her name because Robertson has “contributed so much to reconciliation in the province and actually across the nation,” according to Crawford. The group was proud to nominate Robertson as “someone of such moral strength and personal courage as an example for all Ontarians, so we can walk the same walk as Geraldine; so she can be a role model to us,” said Crawford.

The most difficult part of the nomination process was convincing Robertson herself to allow her name to be put forward, according to Crawford. The group convinced her by saying it would help promote her reconciliation work.

Robertson herself feels the award “was sort of a vindication that I’ve been on the right track. It’s not something I expected; it’s a nice surprise,” she tells Anishinabek News. “I like to keep a low profile; I don’t like to draw attention to myself. I think is worthy in the sense that it draws attention to the topic of of residential schools,” she says.

Whether speaking to small groups or to hundreds, or leading a blanket exercise exposing others to survivors’ experiences, Robertson impresses audiences with “her intelligence combined with the strength in her spirit which comes from her own personal journey,” says Crawford. “She has moved from being a child victimized by adults who had complete control over her to reconciling with her own story.” When she tells her story, Robertson doesn’t “ram it down any throats” and doesn’t get involved in assigning blame, but makes it clear that “I need you to know what happened to me,” in Crawford’s words.

At age 11, after a year at the Mount Elgin school near London, ON, Robertson was sent from Aamjiwnaang to the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, beginning what she has described as a “life in hell”. Suffering loneliness, hunger, strappings from the principal, and dodging attacks from older students, she managed to hang on and even act as protector to her two younger sisters. She was also aware of sexual abuse, inflicted not only by staff on students, but also by older boys on the younger ones.

As a grown married woman with her own children, Robertson started speaking publicly about her experiences to help other parents do a better job of child-raising. It was hard for survivors to be good parents since “their frame of reference for parenting was what they had learned at residential schools; a lot of violence,” she remembers.

Her first speech, in 1995, was to her Chief and Council. Robertson felt programs at Aamjiwnaang, then known as Chippewas of Sarnia, weren’t helping people heal and overcome the inter-generational trauma, and her appeals helped bring programs such as parenting classes, baby wellness programs, and anti-violence workshops to the community.

Since then, she has travelled much of Canada in her work, and has visited many elementary and secondary schools across southwestern Ontario. Robertson has been featured in the documentary “We Are Still Here,” about the experiences of survivors from her area, and her children have been part of the follow-up film “Aftershock”, documenting the lives of survivors’ children.

Her work still continues, with speaking engagements as far off as next July. News of the award came to her as a surprise. “I just never thought that the average, ordinary person would get an award such as the Order of Ontario. I thought it was more of the elite who would qualify,” she says.

Officials with the Order of Ontario have asked Robertson if they can use her story to help promote the Order as an egalitarian honour, open to any and all residents of the province.

Robertson will receive the award in Toronto on Feb. 27.