Jeremy Proulx’s Pane Jaagide Everlasting Fire has world premiere at Neyaashiinigmiing

By Laura Robinson

NEYAASHIINIGMIING FIRST NATION–Hundreds of theatre goers gathered at the Nawash Community Centre in Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation on the Saugeen Peninsula for an evening performance of “Pane Jaagide Everlasting Fire” on September 9.

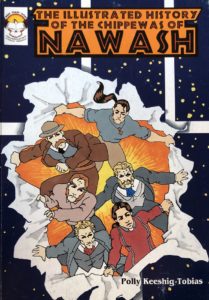

Adapted by actor and filmmaker Jeremy Proulx from the book, “The Illustrated History of the Chippewas of Nawash” by Polly Keeshig-Tobias, the two-act play is a journey of over two-hundred-years, documenting how colonialism nearly wiped out the livelihoods, food and sustenance, culture and traditions of the Chippewas of Nawash and other communities within Saugeen traditional territories.

Proulx’s had a busy summer. He starred as Chief Bromden in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, England, while putting the finishing touches on Pane Jaagide, his first production as a playwright, which Barbara Worthy directed. Both live in Toronto.

Steven Baranyai from Serpent River First Nation acted, helped compose and perform the music for the play, and led a music workshop for young people in advance of the premiere. The warm-up act for Pane Jaagide was a shadow puppet play about the fishery, written and directed by Nawash youth after Shadowland Theatre Co paired up with Baranyai and expanded the week-long arts workshop.

The journey is narrated by Nookimis and Mishomis—grandparents to Polly and Josh, two students who are assigned a history project by their teacher.

“Boring”—says Polly and that is when the story begins.

Through a series of untruths—told most frequently by Sir Frances Bondhead and Lord Oliphant—the play shows how a vast territory was stolen until the Nawash and Saugeen ended up on the parcels of land on which they presently live. However, the play is not one of victimhood—their ancestors did not acquiesce willingly. It was clear if they did not agree to new terms each time Bondhead, Oliphant or the Indian agent rewrote agreements, no justice would be served if violent settlers attacked—no matter what the consequences were to the Nawash.

After this history lesson from Nookimis, “Pane Jaagide” time travels to two pivotal events: the first was in December 1992 when the Nawash lit a Sacred Fire and occupied traditional burial grounds that were never surrendered in the Treaty of 1857 when their land in the Owen Sound area was confiscated.

Under the late Chief Ralph Akiwenzie, they occupied the burial ground of their ancestors at the mouth of Indian River in Owen Sound. Despite frigid conditions, they did not leave until an agreement was obtained with the then Department of Indian Affairs.

Musicians Aaron Berger and Steven Baranyai sang the most haunting of songs about Nahneebahweequa, Upright Woman, or Catharine Sutton, who advocated for all Anishinaabe and farmed on the traditional land of the Nawash, not far from the burial site. The local government confiscated her farm while she was away, and even when she offered to pay them in order to buy it back, they would not recognize the sale of her own land to “an Indian” and turned her away.

Things had changed by 1992. Chief Akiwenzie not only successfully negotiated for the land to be returned, but the two houses that were on it were removed: one was barged up Georgian Bay and today is a home to wisdom and knowledge in the community.

The second pivotal event occurred in 1993 Frances Nadjiwon and Howard Jones won a landmark case—now the “Jones Nadjiwon decision” that showed the Nawash and Saugeen First Nations had never surrendered their commercial fishery that extended the entire reaches of their traditional waters—from north of Goderich on Lake Huron, up the Saugeen peninsula and down into Georgian Bay as far east as Meaford, as well as seven miles out.

That victory signals the end of the stories Mishomis and Nookimis have for Polly and Josh, and the end of the play.

The Maadookii Seniors Group worked with the Owen Sound university women’s club (CFUW) for two years to ensure the play became a reality. After CFUW member Donna Elliott read Keeshig-Tobias’ book, she realized it would make a great play, and approached the author and band council with her idea. They gave the green light, so she went to the CFUW and asked if they could help finance. The group, who believe reconciliation is fundamental to building a more just future, committed to financing and raising more funds, and then approached Maadookii. They too joined in and commissioned Proulx to adapt the book to a play.

Joyce Johnston, an Elder from Maadookii Seniors Group and an organizer and advocate of reconciliation, said she “was so very honoured to have played Darlene Johnston”, the community’s historical researcher at the time of the burial ground and fishery victories. Johnston is also a member of the Nawash band and now a law professor at the University of British Columbia.

High-school drama and English teacher, Harriet Maconaghie, literally brought courtroom drama alive when she read, verbatim, from Peggy Blair’s successful argument in court. Blair was legal counsel to the band. It was the combination of Johnston’s research and Blair’s pointed questions that won back the fishery.

Community member Trevor McLeod paid tribute to their late chief.

“It was a real honour to play Chief Ralph Akiwenzie” he said, after the play received a standing ovation.

To inquire about a performance contact Maadookii Seniors Group: 519 534 4918