Aamjiwnaang First Nation environmental activist teams up with University of Toronto researchers

By Colin Graf

AAMJIWNAANG FIRST NATION—Environmental activist Vanessa Gray is teaming up with researchers from the University of Toronto (U of T) to create new tools for her community of Aamjiwnaang First Nation to fight the effects of pollution from the Chemical Valley plants that overshadow many of their homes.

Gray, who was arrested for shutting down the Enbridge Line 9 pipeline near Aamjiwnaang in 2015, is calling on Aaamjiwnaang citizens to help the U of T team design an easy phone and computer app that will allow them to record their physical reactions to chemical leaks or spills. The idea came to Gray out of frustration with reporting to the Ontario Ministry of Environment (MOE) on incidents such as heavy smoke from plants, or a bad odour or taste in the air. Gray recalls that if only a few people call in, the Ministry treats their calls as “not a big deal”.

“They’re asking you 20 questions and want really good answers from you for anything to move forward. They don’t really want to look at complaints until the whole community calls at once,” she says.

Gray hopes the phone app will encourage the citizens of Aamjiwnaang to record if they develop sore throats, headaches, or other health symptoms following a chemical release. Maintaining these kinds of records creates a database that could be used to convince the government to take action or as evidence in court cases.

Gray adds that the app is not meant to report to MOE, but it could be used to the advantage of Aamjiwnaang by building up their own database of health effects following chemical leaks to the air or spills to the ground or water.

“This way, we’re not working for [the ministry], we’re working for us,” she says.

The idea for the app was born when Gray and her sister Lindsay were interviewed earlier this year by MOE investigators about a huge flare from Imperial Oil’s Sarnia plant in Feb. 2016. The flare lasted for several days, causing a grass fire at a neighbouring chemical plant, and creating alarm among residents in the Michigan community of Marysville, directly across the St. Clair River from Imperial’s operations. During the interviews, the sisters say they felt they were interrogated more like suspects in a criminal case than witnesses. Gray recounted how the investigators were “very invasive” and asking “a million things,” and wanting to know all kinds of details about her movements when the flare affected her.

In an interview earlier in 2018, Lindsay Gray recalled a Ministry official challenging her description of the flare lighting up her room at night when she lived in Sarnia, saying he once lived closer than her to the Imperial plant and it was “no big deal”.

“It made it hard to sleep and made me very uneasy. I felt like the sky was on fire,” she said. “[The investigator] just made it very personal.”

Gray told the officials she had nausea for a few days and headaches. According to Gray, Aamjiwnaang residents felt their windows shake.

During that incident, Imperial released hazardous contaminants including smoke, volatile organic compounds, sulphur dioxide and sulphur compounds, according to a news release from the Ministry of Environment earlier this year.

Based on interviews with eight people, the Ministry stated that Aamjiwnaang and south Sarnia residents “experienced foul odours, noxious fumes, and material discomfort with vibration in houses, excessive noise from the flare, sleep deprivation from the excessive light of the flare, distress and fear.” Throughout the week while Imperial Oil continued to flare and start-up units, residents experienced headaches, nausea, burning sensation in the nose, and difficulty breathing, the Ministry added.

A decision on whether to lay pollution-related charges against Imperial will be made following careful consideration of all of the evidence gathered, said Ministry spokesperson Gary Wheeler, in a recent e-mail, but gave no timeline for a decision.

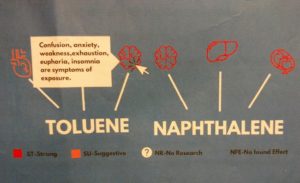

Another part of the researchers’ plan is to allow app users worried about a leak to quickly and easily connect the chemicals they’ve been exposed to with possible health effects.

They hope to start with a separate web page for each of the 75 chemicals emitted by Imperial Oil’s Sarnia operations known to have health effects, including lead, mercury, and known cancer-causers such as benzene. After the website, the group hopes to convert that information into an app where users will be able to click or tap to find health effects from exposure to each chemical.

The group is focusing on Imperial Oil because it was the first oil refinery to set up in Sarnia dating back to 1899, Gray says. The history of Imperial Oil, which originally refined the oil coming from one of North America’s first commercial oil fields near the town of Petrolia, “is the history of Canadian colonialism,” according to Gray.

“The Chemical Valley all started with this one company. For Canada it’s all about resources, there’s no connection to the fact there are Indigenous rights to this territory, human rights to breathe the air. Canada can be very racist about this issue. When Indigenous people are reporting spills at Imperial Oil, it’s more than just that spill, it’s the colonial violence that company represents by existing at all,” claimed Gray in an interview following the meeting.

Imperial spokesperson Kristina Zimmer said that the company has not been contacted by the group, but is open to discussing the researchers’ plans. The company has operated in the area for 121 years and has the largest workforce in the Chemical Valley, with 800 people.

“When you’re larger like that, you tend to stand out more and are perhaps under more scrutiny,” Zimmer said.

Imperial has “consistent two-way dialogue with Aamjiwnaang,” and hopes to continue being part of meetings between industry and the First Nation that started last summer. The company “continues to advocate, as other industries in the Sarnia area do,” for a detailed health study to find out if pollution is affecting the health of Sarnia and Aamjiwnaang residents.

In spite of only a handful of people attending her initial meeting, Gray says she is not deterred.

Earl Cottrelle of Aamjiwnaang First Nation attended the meeting as “a frustrated community member” citing that he is fed up with headaches, contaminants on his vehicle, and the flares and the leaks that aren’t reported. While he thinks there have been improvements in pollution control, Cottrelle said he would use the app Gray’s team hopes to create to record chemical exposures.

He feels Aamjiwnaang should be compensated for living next to the Chemical Valley.

“Why are we in the middle of all this? We should have an arena; we should have the best of everything here,” said Cottrelle.