Epiichiikmaang Nishnaabemwin Dictionary: A progress report

By Mary Ann Corbiere

The Nishnaabemwin-English dictionary commenced many years ago is approaching completion. Several tasks remain. One is to finish the workshops in Wiikwemkoong. Thousands of terms have been compiled over the years. Four other communities have also reviewed these: Walpole Island, Curve Lake, M’Chigeeng, and Sagamok. As eNshinaabemjik reviewed the terms initially compiled, they mentioned many more terms not yet documented. These went into a second list they also reviewed. Still more terms arose entailing a third round of workshops. Once all done, the workshops – done intermittently—will total 160 days spanning several years.

The foremost objective is to guide Annishinabek wanting to learn their language on usage of terms. To this end, a few basic forms are included for each verb. Of course, as eNshinaabemjik and learners of our language know, each verb has many different forms. ENshinaabemjik will know that the number of terms is conceivably limitless given how our language works. My co-author, Rand Valentine, and I could not possibly list all of the words that can be formed, so other words will still come to mind that will have been missed. Nonetheless, this resource will have a much more comprehensive listing than existing dictionaries do.

Many words have meanings that are hard to convey clearly to learners through translations. To add clarity (and illustrate actual speech), example sentences for such terms will be included. Many English verbs are said in several different ways in Anishinaabemowin, each having a specific sense or usage. There are over 15 verbs for touch, for example. Additional information besides example sentences will give further guidance on which verb would be appropriate in a given instance. If a learner checks “touch something” for example, they will see daangaabiisin, the note “of stringlike objects,” and the example sentence “Nniizaanat na giishpin dikning daangaabiising hydro line?” along with its translation, “Is it dangerous if the hydro line is touching a branch?” This demonstrates (we hope), that this verb would also pertain to things like electrical cords.

Proofreading is ongoing; typos inevitably arose given the volume of information involved. Editing will be the final task. We are striving to ensure translations are precise, as concise as possible and natural sounding, especially for those terms that defy easy translation. This involves some hard decisions concerning phrasing. How can we best translate a highly descriptive verb (and a great figure of speech) like bkaabiignikeshkooza? Learners ought to attain proficiency ultimately with terms that have this level of descriptive power. How can we lead them to words of this sort? Should bkaabiignikeshkooza be listed under break or arm or under both terms? Will learners be able to find it relatively easily among the many Anishinaabemowin terms that contain these ideas? The initial English translations I drafted for many terms of this complexity are quite convoluted. Finding clearer and more apt wording often requires considerable mulling. Example sentences for such terms are especially important.

The question of how to present certain kinds of information on usage that learners need to know has been hard to resolve. Many verbs do not fall neatly into the four basic Anishinaabemowin types students learn about. That’s because certain verbs that arise at times in everyday life follow exceptional patterns. A certain food might have made someone sick. Conveying this calls for one such exceptional verb, aakziikaagon. Although a transitive verb, this does not work like either of the two basic transitive verb types. Verbs like the one in the remark “Nwaabmaa” (I see her) typically describe a person doing something to (or with or for) an animate object. How should we label a verb like aakziikaagon where it’s an inanimate thing that’s doing something to a person? The linguistics perspective my co-author brings to such questions is indispensable.

The assorted information warranting inclusion makes design of the dictionary layout another critical task. The database expert on the Algonquian Linguistic Atlas team is providing vital support on this matter. The atlas is an online platform created to hold electronic resources on Algonquian languages, this dictionary being one such resource. That electronic tools are virtually indispensable for dictionary work was something I didn’t realize when I began. They enable a great amount of information to be stored and available to users.

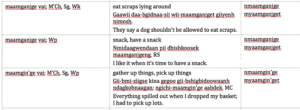

The time the remaining tasks will take is hard to predict, but my sabbatical (until June 2020) is enabling steadier progress. This report I hope assures those waiting that there will be online, though not a thorough compilation, at least a much more comprehensive dictionary by summer 2020. Nda-piichiikaanaa go (we’re working on it). The picture shows the preliminary format the word lists have for proofreading before the technical experts put the content online. Cost factors will make the print dictionary we’ll also produce necessarily abridged.