Artist reconnects to roots in Aamjiwnaang

By Colin Graf

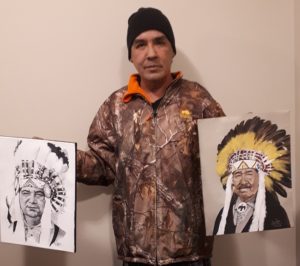

AAMJIWNAANG FIRST NATION— A series of painted portraits of his First Nation’s Chiefs is both a thank-you gift to his community from artist Richard (Darren) Cottrelle and a form of therapy helping to reconnect to his roots and overcome years of substance abuse.

Since returning to his birth community last April, Cottrelle has completed five portraits of Chiefs from different generations dating back to the 1800s. The idea came to him after returning to Aamjiwnaang after many years away, some of them spent in a downward spiral of alcohol abuse and jail time.

Cottrelle says he wanted to give something back to the community after he returned with nothing but a few clothes, living at a campsite with his dog. People first started giving him tents and food, and later arranged for an apartment for him and furnished it.

So far, he has completed five Chiefs’ portraits, dating from Joshua Wawanosh, the hereditary chief who signed Treaty 29 in 1827, ceding large parts of southwestern Ontario, up to Ray Rogers, chief from 1976-88 and 1998-2000. Others include Fred Plain, who proposed to the federal government in 1969 that seats be set aside in the House of Commons for Canada’s First Nations, according to Aamjiwnaang historian David Plain in his book, The Plains of Aamjiwnaang. Also included are Aylmer Plain, served 1969-70, and Gerald Maness, 1970-76.

Cottrelle works mostly in acrylic paint on canvas, and has painted the Chiefs’ portraits from photographs he finds on the internet or those brought to him by people who have heard about his project or have seen his works. He hopes to finish the project by this summer. Each one has taken about a month to complete— working “a little bit here and there” in between commissioned works.

Cottrelle hopes to complete four more, including current Chief Christopher Plain, and recent Chief Joanne Rogers, 2016-18. He hopes the paintings will hang in a public place, such as the band council office or community centre.

He says interest in the Chiefs’ portraits is growing.

“The whole community is interested, everybody’s excited to see who the next [Chief] will be,” he says.

Cottrelle has created other part pieces honouring First Nations leaders, completing a series of Elders’ portraits for the Native Canadian Centre of Toronto, and a similar series in black and white for the casino in Sault Ste. Marie.

Cottrelle discovered his love for creating art as a child, but never had formal training. Pursuing a career as an artist while battling alcohol addiction, he found he was using money earned by selling art to pay for drinking.

“I would sell my art real cheap. I had no marketing skills,” he recalls.

Cottrelle thinks he has spent about half of his life in 18 different correctional facilities. He first started doing portraits in jail, and honed his skills there.

“I spent a lot of years in and out of jail before I got sober eight years ago,” Cottrelle explains. “Then I was able to do full-time work.”

He started making better decisions about his life and art career, he says.

“My business had more foundation then,” explains Cottrelle. “I wanted to show people you can get sober, you can put down the bottle, and you can quit drinking if you really want to, there’s a choice you have to make. You can choose to die or you can choose to live, so I chose to live, and I went into treatment.”

Art played a large part in Cottrelle’s recovery. While during his dark years his art expressed a lot of anger, Cottrelle now finds his art “generates a lot of positivity.”

In returning to Aamjiwnaang, Cottrelle hopes people can say, “Here’s a man who has come a long way.”

He suspects people may only remember him as someone who “partied every day” and ended up losing his land at age 21.

Coming full circle, Cottrelle hopes today to rebuild on the property and end the cycle of alcoholism that led to the surrounding woods, littered with wine and liquor bottles, to be nick-named “Heartbreak Forest.”