My Sacred Promise to Moochum Joe

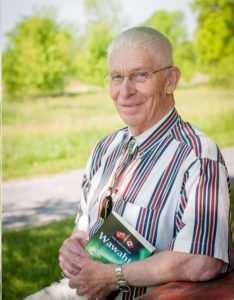

By Bob Wells

At age nine, I made a “Sacred Promise” to my friend Moochum Joe that “I will draw words on paper telling my kind how bad Indian People are treated.” This presentation is part of my promise from years ago.

The teachers central to my upbringing were my white Christian parents and Moochum Joe, an Anishinabek Elder. Most of my kind thought Moochum Joe to be an “illiterate and lazy old Indian”. He was my dear friend and an unforgettable teacher. He taught me as a child to learn from my five senses. From his hours of teachings about respecting all life, great ancestral hunters, and the forest spirits, I began to understand that humans are neither more nor less than a part of nature. In contrast, most ‘white people’ in my youth believed that Canada was a challenging wilderness to triumph over and that pushing aside Indigenous residents was an imperialist and divine right. In hindsight, there was little or no consideration for the human and environmental after-effects.

Today, we must acknowledge that reconciliation is not an event; it is finding things that we can do together to right past wrongs. Many Canadians now know about the harsh facts of residential schools, Indian hospitals, the Sixties Scoop, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, how repressive the Indian Act and Indian reserve system have been to both communities and individuals.

I received my elementary education on a School Car and homeschooling and attended an excellent highschool in the state of Wisconsin and turned down a free university education. Instead, I chose a life of being a fishing/hunting guide, fur-trapper, and a thirty-year career as an Ontario Conservation Officer. My wife Inge immigrated to Canada from Germany in the mid-1950s’. Her childhood and education were interrupted by bombs dropped during World War II.

Looking back, we have had the most extraordinary life. I do not know where we would be without it. But, I/we think that the greatest gift it has given us is the opportunity to use our voice for the voiceless.

I have been thinking a lot about some distressing issues we are facing collectively, and at times, we feel or are made to feel we champion different causes. Regardless of what we defend, I see a commonality. I think whether we’re talking about gender inequality, homosexuality, religion, racism, Indigenous rights, or animal rights, we are talking about the fight against injustice. We are talking about the argument that no one nation, no one peoples, no one gender has the right to dominate, control, and use or exploit another with impunity. I think we have become very disconnected from the natural world and many of us have an egocentric worldview. The belief that we are the center of the universe.

I think we fear the idea of personal change because we have to give something up. However, human beings, at their best, are so creative and ingenious. I think that when we use love and compassion as our guiding principles, we can create, develop, and implement systems of change that are beneficial to all sentient beings and the environment.

We have a second chance: I think we are at our best when we support each other not when we cancel each other for past mistakes but when we help each other to grow, when we educate each other, when we guide each other towards redemption— that is the best of humanity.

The wrongs committed over seven generations were awful. We must move away from ingrained behaviour, and in time, reconciliation will lead to restoration. Restoration is the willingness to resolve problems and hinges on our desire to communicate with each other about the possibilities of an alternative future.

The core question that underlines each communication is, ‘What can we create together?’ Shifting the context from retribution to restoration will occur through language that moves from problems to possibility, from fear and fault to gifts, generosity, and abundance, from law and oversight to social fabric and chosen accountability, from corporations and systems to associational life, from leaders to citizens. The situation is simple. Indigenous Peoples have made and will continue to make a remarkable comeback. Non-Indigenous Canadians have a choice to make: to stand in the way or to be part of a new narrative. In my way, I have tried to keep the promise I made to Moochum Joe to accept “clear responsibilities, expectations, and accountabilities.”

All of us can and need to create Canada different from the past. Future Canadians will judge us on the history we create.