The Rice Lake purchase

By Dr. David Shanahan

At the start of the War of 1812, 60% of the population of Upper Canada was American-born, and this was a security concern for the Crown throughout the conflict. Would those people join an American invasion? Most of the fighting in the war took place in the western part of the province, around the Niagara Peninsula, and communication between that region and Montreal was tenuous at best. Even before the war ended, it had been decided to establish an assisted immigration scheme to bring disbanded soldiers to Upper Canada along with civilian immigrants from Scotland and Ireland. Between them, these immigrants would provide a settled and dependable population to deal with any future conflict with the United States.

The plan was to settle the entire area between the Ottawa River and Lake Erie to prevent incursions by the Americans in any future wars. The Crown turned to the Rice Lake Mississaugas, seeking to acquire the territory behind Rice Lake to use for settlement. The Crown believed that all of this land had been included in the Crawford Purchases back in 1783-84, but this was disputed by the Mississauga, and it was decided to simply make a new Treaty with them to avoid any doubts arising. As William Claus, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs, said in his address to the assembled Chiefs at Port Hope on November 5, 1818, he wanted “to put at rest the doubts with respect to the lands in the back parts of this Country which you seem to think were never disposed of to the King”.

Claus also informed them of a new approach to treaties that the Crown was taking, providing annual, instead of the one-time, payments. This was apparently most acceptable to the Chiefs, who had found their traditional lands incapable of sustaining their people. The principal Chief, Buckquaquet, stated openly that “if it was not for our Brethren the farmers about the Country we should near starve for our hunting is destroyed.” White settlement had been moving into the townships to the rear of the St. Lawrence front since the 1790s, and wildlife had been driven away and hunted to extinction by the increased population of settlers.

Buckquaquet asked that the right to hunt and fish what remained on their territory would be allowed to them under the treaty, and that they would be protected from any negative actions by the new immigrants moving into the region. Claus simply stated that the rivers and forests were open to all, immigrant and Mississauga equally.

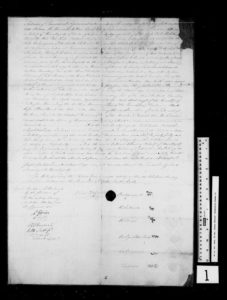

The Rice Lake Purchase was signed on November 5, 1818, by various Chiefs and “Principal Men of the Chippewa Nation of Indians inhabiting the back parts of the New Castle District.” The Chiefs each signed using their clan affiliations (“Buckquaquet, Chief of the Eagle Tribe; Pishikinse, Chief of the Rein Deer Tribe; Pahtosh, Chief of the Crane Tribe; Cahgogewin of the Snake Tribe; Cahgahkishinse, Chief of the Pike Tribe; Cahgagewin, of the Snake Tribe; and Pininse, of the White Oak Tribe”).

The land ceded under this treaty was extensive: 1,951,000 acres, for which the Rice Lake Mississauga were to receive “the yearly sum of the seven hundred and forty pounds Province currency in goods at the Montreal price to be well and truly paid yearly, and every year, by His said Majesty to the said Chippewa Nation”.

At a subsequent meeting, Claus clarified the method of payment of the annuity promised in the treaty. This was necessary, said Claus, “in order to obviate any difficulty or misconstruction which might hereafter arise”. The £740 would be distributed on a per capita basis, each man, woman and child receiving $10.

The Rice Lake Purchase was just one of a series of “treaties” which the Crown negotiated following the end of the War of 1812. It opened up the lands to the north of Lake Ontario, giving an unbroken tract for settlement from the Quebec border to the Detroit River and Lake Erie. It was an essential move for the Crown in terms of settlement and military purposes, but the effects on the Indigenous people were far-reaching, permanent, and not nearly as positive.