The Great Gathering

By David Shanahan

When William Johnson met with 24 nations at Niagara in 1764, one of the promises made by him on behalf of the British Crown was that as a sign of how important the alliance with the Indigenous nations was, the Crown would give gifts to them. These presents, as they became known, would be given every year at a special ceremony. The Ottawa, Ojibwa and Potowatomies of Lakes Huron and Superior and the Michigan territory were paid at Drummond Island until that place was transferred to the Americans. In 1836, the presents were distributed at Manitoulin, on the small island off Manitowaning. A visitor there in 1837 wrote an account of the meeting and described the scene. Anna Jamieson was an English woman travelling through Upper Canada and arrived at Manitowaning by canoe.

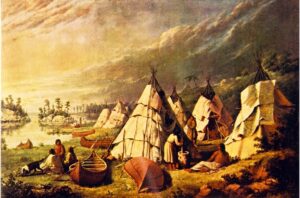

“This bay is about three miles wide at the entrance and runs about twelve miles in depth, in a southerly direction. As we approached the further end, we discerned the whole line of shore, rising in bold and beautiful relief from the water, to be covered with wigwams, and crowded with Indians. Suddenly, we came to a little opening or channel, which was not visible till we were just upon it, and on rounding a promontory, to my infinite delight and surprise, we came upon an unexpected scene —a little bay within the bay. It was a beautiful basin, nearly an exact circle of about three miles in circumference. In the center lay a little wooded island, and all around, the shores rose sloping from the margin of the lake like an amphitheatre, covered with wigwams and lodges, thick as they could stand amid intermingled trees; and beyond these arose the tall pine forest crowning and enclosing the whole. Some hundred canoes were darting hither and thither on the waters or gliding along the shore, and a beautiful schooner lay against the green bank—its tall masts almost mingling with the forest trees, and its white sails half furled and half gracefully drooping.”

The scene was almost overwhelming to her as there was no other event at which so many people from so many nations and places came together in one place. There were 3,700 Indians, Ottawas, Chippewas, Pottowottomies, Winnebagos, and Menomonies, encamped on the island, and the gathering lasted for days, as this was more than just a time for presents, it was also a social and political meeting of many nations.

Every individual had to be there in person to receive their share of the goods, which Jamieson listed.

“The common equipment of each chief or warrior (that is, each man) consisted of three-quarters of a yard of blue cloth, three yards of linen, one blanket, half an ounce of thread, four strong needles, one comb, one awl, one butcher’s knife, three pounds of tobacco, three pounds of ball, nine pounds of shot, four pounds of powder, and six flints. The equipment of a woman consisted of one yard and three quarters of coarse woollen, two yards and a half of printed calico, one blanket, one ounce of thread, four needles, one comb, one awl, and one knife. For each child, there was a portion of woollen cloth and calico. Those chiefs who had been wounded in battle, or had extraordinary claims, had some little articles in extra quantity, and a gay shawl or handkerchief. To each principal chief of a tribe, the allotted portion of goods for his tribe was given and he made the distribution to his people individually; and such a thing as injustice or partiality on one hand, or a murmur of dissatisfaction on the other, seemed equally unknown. There were, besides, extra presents of flags, medals, chiefs’ guns, rifles, trinkets, brass kettles, the choice and distribution of which were left to the superintendent, with this proviso, that the expense, on the whole, was never to exceed nine pounds sterling for every one hundred chiefs or warriors.”

A valuable part of Jamieson’s account is the list of Chiefs who took part in the event and in the council, which took place after the presents were distributed.

“There was my old acquaintance, the Rain, looking magnificent, and the venerable old Ottawa Chief, Kish,ke,nick, (the Cut-hand.) The other remarkable chiefs of the Ottawas were Gitchee, Mokomaun (the Great or Long-knife); So,wan,quet (the Forked-tree); Kim,e,ne,chau,zun (the Bus¬ tard); Mocomaun,ish (the Bad-knife); Pai, mau,se,gai (the Sun’s course in a cloudless sky); and As,si,ke,nack (the Black-bird). The latter a very remarkable man of whom I shall have to say more presently. Of the Chippewas, the most distinguished chiefs were Aisence (the Little Clam); Wai,sow,win,de,bay (the Yellow-head); and Shin,gua,cose (the Pine); these three are Christians. There were besides Ken,ne,bec,ano (the Snake’s-tail); Muc,konce, e,wa,yun (the Cub’s skin); and two others whose style was quite grandiloquent—Tai, bau,se,gai (Bursts of Thunder at a distance) and Me,twai,crush,kau (the sound of waves breaking on the rocks). Nearly opposite to me was a famous Pottawatomi chief and conjuror, called the Two Ears.”

Finally, Jamieson described one individual in particular, Waub-Ojeeg, the son of Wayish,ky. For an English woman in the Nineteenth Century, this was an occasion, and a figure, quite outside her experience.

“…in height he towered above them all, being about six feet three or four. His dress was equally splendid and tasteful; he wore a surtout of fine blue cloth, under which was seen a shirt of gay colours, and his father’s medal hung on his breast. He had a magnificent embroidered belt of wampum from which hung his scalping-knife and pouch. His leggings (me-tasses) were of scarlet cloth beautifully embroidered, with rich bands or garters depending to his ankle. ‘Round his head was an embroidered band or handkerchief in which were stuck four wing-feathers of the war-eagle, two on each side—the testimonies of his prowess as a warrior. He held a tomahawk in his hand. His features were fine and his countenance not only mild but almost femininely soft. Altogether he was in dress and personal appearance the finest specimen of his race I had yet seen.”

The presents had been promised by the Crown “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows, and the waters run”. The sun continued to shine, the grass to grow, and the waters to run; but the Crown ended the presents in 1858.