Chenail Ecarte Purchase: September 7, 1796

By David Shanahan

By David Shanahan

Even after the end of the American War of Independence, the British Government continued to hold the main forts which were at the centre of the fur trade and relations with the First Nations. The Detroit Fort was especially useful and was a main contact point between the British and the Nations in the United States still resisting American incursion into their lands. The British aim was to see an Indian buffer state established that would lie between the United States and the British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada.

Upper Canada had been established in 1791 out of the Indian territory that had been acquired under the many treaties negotiated after 1783. It was particularly vulnerable to American attack, and so it was in Britain’s interest to promote an Indian state. After major Indian victories over American armies in 1791 and 1792, Britain offered to mediate between the warring parties. The US refused the offer categorically.

Nevertheless, the British continued to request that they be allowed to send representatives to talks between the two sides, and in 1792 and 1793, an officer in the Indian Branch in Canada, Alexander McKee attended these meetings. McKee had been instrumental in negotiating a number of the treaties for the Crown and maintained very good relations with the various Nations on both sides of the Niagara and Detroit borders. The Americans, however, refused to allow him to speak or have any official standing at the talks, which were unproductive because of divisions among the Indians themselves.

The hopes for an independent Indian country ended on August 20, 1794, when the American forces won a major military victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The Americans finally managed to destroy the military power of the Northwest Indians. This began a long series of talks between Britain and the US leading up to the Jay Treaty of November 19, 1794, which included an agreement to return the forts at Detroit, Niagara, and Michilimackinac. The Treaty was only confirmed by the American Senate after much debate and division, on June 24, 1795, and it only came into effect on February 29, 1796.

There was an assumption on the part of the British that the ending of the resistance by the Northwest Nations would result in a flood of people moving across the border into Upper Canada, away from American jurisdiction, and it was decided to acquire lands across from Detroit on which they could settle. McKee was instructed to approach the Chippewas of the Chenail Ecarte, immediately to the north of the lands taken under the treaty in the McKee Purchase of 1790. McKee believed that as many as two or three thousand people would be coming across the border, and he reached an initial agreement with the Chippewas for a tract 12 miles square on the St. Clair River on which these newcomers could settle.

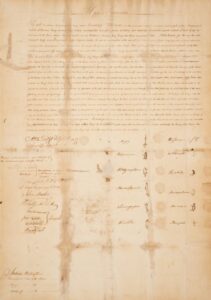

At a formal council held at Chenail Ecarte on August 30, 1796, McKee emphasized that the land being treated for was not for the use of the Crown, “but for the use of his Indian children and

you yourselves will be as welcome as any others to come and live thereon.” The Treaty was signed on September 7, 1896, and made no mention of the purpose for which the land was being ceded to the Crown. The deed was witnessed by three Ottawa Chiefs who had also attended the treaty gathering. In return for ceding the four square leagues, the Chippewas of Chenail Ecarte received £800 worth of goods, all of which are listed and inventoried in an appendix to the Treaty.

The expected influx of Indian refugees from the United States never materialized. The land ceded under the treaty was surveyed as Shawnee Township, though the name was later changed to Sombra Township and was opened to white settlement.