The Crawford ‘Purchases’

By Dr. David Shanahan

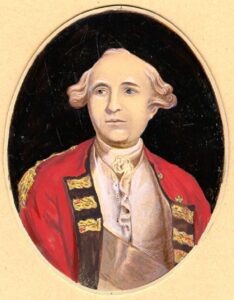

The end of the American War of Independence saw around 3,000 refugees moving into the territory south and west of the Ottawa River, land that had been declared “Indian Territory” by the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In keeping with the terms of the Proclamation, and in order to continue to mollify the indigenous residents of those lands, the “Captain General and Governor in Chief in and over the Province of Quebec in America”, Frederick Haldimand ordered that the lands required should be negotiated for with the Mississauga and Mohawks before townships could be settled, although the surveys went ahead in advance of the negotiations.

It was a delicate task. When the details of the Treaty with the Americans became known in North America, the fact that the Indigenous allies of the British had been betrayed was kept from them. But, by May 4, the bad news was generally known and Haldimand was assured by his military officers that they would do whatever they could to “console” their allies, whose resentment was growing. It was well remembered what their response had been after the previous Treaty of Paris 20 years earlier, and no one wanted to deal with another Indigenous uprising like the Pontiac Rebellion had been.

In August, the official in charge of Indian Affairs, Sir John Johnson, met with the Mississauga and found that they were uneasy about the Haudenosaunee settling around Cataraqui, as had been planned. On September 15, Haldimand informed Major John Ross, commanding at Catarqui, that Johnson would be treating with the Mississauga, who claimed the lands north of Lake Ontario, for the purchase of their lands, to remove the uneasiness which they felt. Haldimand was aware that the Mississauga would be unhappy if they knew the Haudenosaunee were planning to settle on the lands around the Bay of Quinté:

From the Report of Sir John Johnson I have reason to expect that the Mohawks and some other Tribes of Savages will establish themselves near the Bay of Kintie, and I understand that it is their Wish to have the Loyalists in their Neighbourhood, all which I think will be an Advantage, by rendering the Settlement respectable, and consequently secure -The Only difficulty seems to be, giving uneasiness to the Missisagues, as they claim The Northern Part of Lake Ontario, to avoid which, I have directed Sir J. Johnson to treat with them on this matter and if necessary to make such purchases as the King’s Service may require, which he tells me will easily be accomplished.

The job of arranging the purchase with the Mississaugas was given to Captain William Redford Crawford, who had held lands as a tenant of Sir John Johnson and was a captain in the 2nd Battalion, Kings Royal Regiment of New York during the Revolutionary War. Crawford met with Mississauga Chiefs on Carleton Island in October, and reported to Johnson on his success:

According to your directions I have purchased from the Mississaguas all the lands from Toniata or Onagara River to a river in the Bay of Quinte within eight leagues of the bottom of the said Bay including all the Islands, extending from the lake back as far as a man can travel in a day.

In return for the territory, the Mississauga were to be supplied with clothes, some weapons, and “as much coarse red cloth as will make about a dozen coats and as many laced hats”. The precise quantity of land depended on how one defined “as far as a man can travel in a day”, but the tract lay north of a line from Jones Creek just above Brockville to the Bay of Quinté.

It was believed that the Mississaugas were satisfied with having the Loyalists come and live among them. But time would change their minds, once it became clear that the newcomers assumed ownership of lands the Mississauga thought they had simply agreed to share. Significantly, Crawford also noted that, although three Haudenosaunee chiefs from the Onondagas around Montreal were present at the meeting, “Not a word was said in regard to the Mohawks”. The urgency in acquiring the lands was underlined by Haldimand’s Military Secretary, Robert Mathews, in a letter to Ross. The purchase had to be made in time to allow the survey of townships on which to settle the refugees. To “facilitate” the acquisition, Mathews had sent a supply of rum to Ross, of which he expected “a proper expenditure…of such quantities as you shall from time to time have occasion for”.

Ross reported the purchase negotiated by Crawford to Mathews on October 15, noting that: “no mention was made of the Six Nations settling on the Lake, lest the Mississagoes might be unwilling to treat”. There was, in fact, no actual Surrender or Sale document recording the purchase. In forwarding the news about the purchase to Haldimand, Johnson asked for directions as to whether such a deed would be required. There is nothing to indicate that any such deed ever existed. The importance of the rum supply was confirmed by Ross in a letter to Mathews on November 3:

I am much obliged to His Excellency for the Order on Carleton Island for Rum; such is the nature of the Indians here, that is their services are wanted, they are exceedingly covetous, but if they are not employed seldom ask for anything, as the latter is mostly the case at present a very small quantity of Rum or provisions will satisfy them, both which shall be managed with the greatest economy, indeed of late I have greatly weaned them from both and without any Disscontent. This Nation is Peaceable times will be of very little expence to Government.

Whatever extent the use of rum facilitated the purchase from the Mississauga is unclear, but another Chief, Mynass from Kanesatake, west of Montreal, had also “sold” his lands for clothing at the October meeting at Carleton Island. But he claimed, and his claim was accepted apparently without question, all the lands from “River Toniato to Cataraqui”, and stretching from the Saint Lawrence to the Ottawa River. It does seem that these lands claimed by Mynass overlapped those “sold” by the Mississaugas. To say that these “purchases” of lands from the Mississauga and Mynass were irregular and, under the terms of the Royal Proclamation, likely invalid, would be a major understatement.