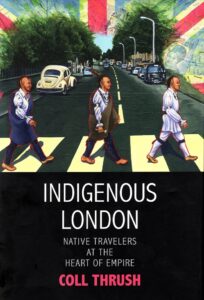

Book review: Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire

Coll Thrush’s Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire contains an appendix that offers a guided tour to the various sites and sights that Indigenous peoples visited and saw when in London from the 1500s to the 1800s. The entire proceeding monograph serves as a detailed narrative for the ‘appendix tour’ that succinctly ties the past to the contemporary. This makes Indigenous London a marvellous read for travellers, historians of London and Indigenous peoples, as well as anyone interested in a masterful story of how Indigenous peoples influenced the Empire. Simply, Thrush seeks to “reframe the history of a city through Indigenous experiences” (ix).

Thrush utilizes multiple stories of Indigenous visitors to London to deftly cast Indigenous travellers as real people with real power and a shared humanity rather than “powerless victims or powerful metaphors”(16). Throughout Indigenous London, the popular and oft unquestioned notion that the city and the Indigenous are antitheses to each other is shown as a construction of Western convention and colonialism. Thrush, by showing how Indigenous travellers engaged with the city and its denizens, contributed to the creation of the ‘modern world.’

While the text clearly shows that London was and remains the birth place of British settler colonialism, Indigenous travellers, whether Ojibwa, Inuit, Maori, Aborigine, Hawaiian, or Cherokee, through their presence, actions, and voices, framed themselves as part of modernity. Indigenous Peoples did this as they sought to engage with Empire as equals to protect Indigenous communities, territories, and sovereignties, as well as trade. Similarly, according to Thrush, Indigenous travellers, regardless of time period, were concerned about the ecology of the city (i.e., the smog, filth, and lack of food security), violence and persistent alcohol abuse, as well as profound inequalities in wealth they witnessed. While these observations were cast by the press as typical of ‘primitive’ peoples, Indigenous views matched British concerns about London’s pressing urban issues. Nevertheless, Indigenous travellers were represented as physically removed from urbanity (the primitive) by the press and would be eventually eliminated (or forgotten) from the city’s narrative – the key defining elements of settler colonialism through physical and narrative removal.

Indigenous London also illustrates how Indigenous visitors influenced contemporary British culture while experiencing it. Thrush explores how Indigenous travellers were intimately connected to the seats of power through meetings and visits with aristocrats, royals, leading intellectuals, and religious leaders. The spectacle of Indigenous visitors incorporated into plays, operas, and songs. For instance, Shakespeare incorporated Indigenous people into his plays in the 1500s while Stephen Storace’s opera, The Cherokee, created the stereotypical sound of Indigenous drums in 1794. Similarly, nineteenth century Indigenous sportsmen – such as New Zealand rugby players, Aborigine Cricket players, and a Seneca Runner – both challenged and reinforced Victoria notions of and concerns about contemporary British masculinity. In short, Indigenous visitors contributed to London and by extension, Britain’s view of itself and the world it was creating in a myriad of ways.

In the final chapter, “Remembering and Reclaiming Indigenous London, 1982-2013,” Thrush connects contemporary re-remembering and Indigenous survivance to London’s ‘forgetting’ or ‘uncomfortable’ relationship to its imperial colonial past. Here he ties the Indigenous presence and urban space from past to present, thereby showing how Indigenous London continues to exist. These ongoing connections and influences are further highlighted in the epilogue where Thrush notes how Indigenous reconciliation and rewriting of histories has influenced presentations of London’s own Indigenous (i.e., post-glacial) history in an effort to re-imagine the humanity and agency of its past peoples. In making these connections, the epilogue and appendix illustrate how Indigenous people continue to influence the heart of the now former empire’s understanding of itself, its past, present, and future in an ongoing dialogue.

Overall, this is an excellent and engaging book. It is a must-read for anyone interested in Indigenous people in London and their impact on Empire, through their agency, presence, and humanity – we were not passive victims or metaphors.

Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travelers at the Heart of Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.