Book review: Deadly Aim: The Civil War Story of Michigan’s Anishinaabe Sharpshooters

Reviewed by Karl Hele

Reviewed by Karl Hele

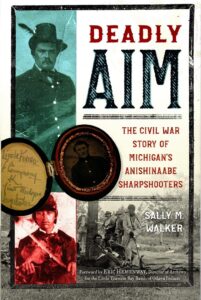

Sally Walker’s Deadly Aim: The Civil War Story of Michigan’s Anishinaabe Sharpshooters is a well written text that follows Anishinaabeg men who served in Company K of the First Regiment of Michigan Sharpshooters during the United States Civil War. The work is heavily informed by the descendants of those who served as well as records of the company. This led Walker, while telling the story of Company K, to focus on specific individual experiences – from training to combat to prisoners of war. As Walker follows the history of Company K, she provides cultural and general historical context to provide greater depth to the men’s experiences during the war. This allowed Walker to craft a text that will appeal to a variety of readers interested in Anishinaabeg and Civil War history.

The book begins with events leading up to the Civil War – the political fight over ending slavery. Chapters two and three highlight Anishinaabe culture, treaties, as well as conflict with settlers and land loss in Michigan. Chapters four through six explore why Anishinaabe men enlisted and their experiences while training. For instance, Walker notes that while each man enlisted for a variety reasons, many seemed to hope that by fighting for the Union the United States, it would show more respect for the Anishinaabe. Other reasons may have included fear of a Southern victory, call to the tradition of Ogitchedaw, money, adventure, and to look after enlisted relatives and friends. Walkers’ discussion of training highlights the Anishinaabe ability to easily pass sharpshooter qualifications, annoyance with constant drilling, and experiences with racism. Chapters seven through 11 follow Company K in combat as people were killed, wounded, captured, or reported missing. Chapter 12 specifically traces the experiences of Anishinaabe prisoners of war. For example, Walker describes the experiences of Amos Ashkebugnekay, Louis Miskoguon, and Jacko Penaiswanquot in the notorious Andersonville prison camp, as well as Amable Ketchebatis and others’ experiences in a variety of Southern prison camps. In these camps, men starved, faced ill treatment, developed scurvy, and contracted various diseases – those who survived the prison experience suffered lifelong ill health. Chapter 14 discusses the end of war, the company’s disbandment, and the men’s return. Finally, the epilogue provides details of individual lives and deaths after the war.

As a general audience work, Deadly Aim will appeal to readers from highschool and beyond. It is a good starting point to learn about Michigan’s Anishinaabe who fought for the Union during the U.S. Civil War. My only caveat is that occasionally, the cultural or other material she provides for context seems obvious – perhaps this is due to an assumption that the intended audience lacks certain understandings. This obviousness is easily ignored or passed over as you follow the story of Anishinaabe Ogitchedaw in the Civil War. Overall, this is a good, interesting, and thoughtfully-written read.

Sally M. Walker, Deadly Aim: The Civil War Story of Michigan’s Anishinaabe Sharpshooters. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2019.

ISBN: 978-1250125255