Opinion: A respectful Indigenous stereotype

By Maurice Switzer

It seems there are stereotypes that really do honour Indigenous peoples.

Thankfully, cartoonish depictions of Native Americans on the uniforms worn by professional athletes are on the decline — it’s no longer fashionable to root for Redskins. We don’t see ads for Crazy Horse malt liquor, Eskimo Pie ice cream bars, or Indian Red crayons.

We still have to tolerate loonies who think their “tomahawk chop” will inspire the home team, or wear chicken-feather headdresses for Halloween, but that end of the gene pool is getting pretty shallow.

Generations of sports fans, from high school to professional levels, have long claimed that their use of appropriated tribal images and team names are intended to “honour” Indigenous peoples, and that their use mystically bestows supposed “warrior” attributes on their team’s players. It didn’t work too well for baseball’s Cleveland Indians, who won only two World Series titles in 120 years of wearing the grotesque Chief Wahoo caricature before ditching it and changing their name to the more sedate “Guardians.”

On the other hand, military appropriation of Indigenous names and logos has seemed to represent a more genuine appreciation of historic bravery.

North American soldiers have shown a particular penchant for attaching Indigenous names to their weaponry, somewhat ironic given the military’s role in breaking treaties and stealing land from the first peoples they encountered on this continent.

U.S. troops fly Black Hawk, Chinook, and Apache helicopters. Canadian sailors have swabbed the decks of Iroquois Class destroyers christened Huron, Haida, Micmac, Nootka, and Cayuga, to name just a few. If settlers really wanted to honour Native Americans, they might consider using Indigenous-language words, instead of exonyms (English-language labels they adopted because the original ones were too hard for them to pronounce. There is an Algonquin Regiment in North Bay, a reservist group whose armoury is on Chippewa Street, a double-barrelled pseudo-Indigenous misnomer).

Maybe William Tecumseh Sherman’s dad went a bit too far in naming his son after the Shawnee Chief who helped Upper Canadian forces beat back Yankee invaders in the War of 1812. The Civil War general likely took a lot of kidding from his West Point classmates before he graduated to a career of killing thousands of Confederate soldiers and civilians.

Military claims to pay tribute to Indigenous fighting prowess seem more genuine and appropriate than those made by rugby players. Their armies have seen Indigenous soldiers in battle, which is more than you can likely say for most halfbacks or third basemen.

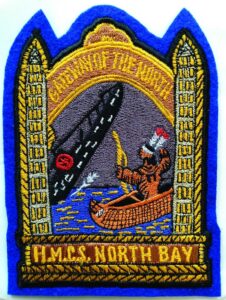

Which brings us to the gun shield of Her Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) North Bay, one of dozens of Canadian vessels that bore the name of this country’s cities and towns in World War II.

HMCS North Bay was christened in 1943 at Collingwood shipyards, joining Sudbury, Cobalt, and Timmins as Canadian Navy corvettes, the smallest warship class vessels.

This fall, the North Bay Museum will mount an exhibit honouring the role of the city’s namesake ship in the Battle of the Atlantic, in which the primary task of Canada’s 123 corvettes was escorting convoys carrying hundreds of thousands of tons of supplies to the British Isles besieged by Nazi Germany.

In January of 1944, North Bay made the first of 15 successful transatlantic crossings from Newfoundland to Ireland, eluding an estimated 1,100 German submarines intent on disrupting the supply chain that proved instrumental in turning the tide of the war.

It was common practice for ships’ crews to boost morale by mounting plaques in various places that touted their determination to defeat the enemy. Designed by Price Signs in North Bay, two metal plaques were attached to the gun shield of the largest piece of armament aboard the corvette, a four-inch foredeck cannon.

Engraved on the plaques was an image of an Indigenous man in a canoe, releasing from his bow an arrow that has pierced the side of a German U-boat, causing it to sink. The fanciful scene was framed by North Bay’s familiar “Gateway of the North” arch.

Yes, it was a stereotype, but one that would be unlikely to cause any criticism on this side of the Atlantic in a war in which as many as 8,000 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit men and women wore Canadian uniforms.

Following World War II, naval headquarters in Ottawa returned the ship’s plaque to the city, where it was refurbished, unveiled in a public ceremony, and later placed on display at Legion Branch 23.

“Along with the ship’s bell and a scale model of HMCS North Bay, the plaque will be one of the main artifacts in this fall’s exhibit,” says acting museum curator Grace Armstrong. “There will also be photos and a Canadian War Museum painting by Thomas Wood of crew members writing letters home.”

One of those letters, reprinted in Cuthbert Gunning’s book, HMCS North Bay: One ship’s role in war and peace, 1943-1992, was written by stoker William E. Bacon, whose cure for seasickness was “…a loaf of dry stale bread. Every time I threw up, I went back to gnawing on (it).”

Maurice Switzer is a citizen of the Mississaugas of Alderville First Nation. He is a member of North Bay Museum’s advisory committee.