Opinion: Is It time to review Métis Nation of Ontario Relationship Agreements?

By Catherine Murton Stoehr

Things have been said that cannot be unsaid:

“The Chiefs of Ontario do not recognize the MNO [Métis Nation of Ontario] as a legitimate organization.”

“The MNO so-called Métis ‘communities’ and ‘territories’ simply and clearly do not exist in Eastern Ontario,” statement by the Manitoba Métis Federation.

“The MNO is, and always has been, a corporate organization that seeks to appropriate First Nations’ identities, territories and rights to benefit the members of its organization,” excerpt from joint letter from 13 duly elected southern Ontario Chiefs.

These are a few of many statements now in the public record asserting that the corporation that calls itself the “Métis Nation of Ontario” (hereafter the “MNO”) does not have authority to speak or negotiate on behalf of Métis people living in what is now called Ontario.

This very public challenge poses a serious problem for the hundreds of mining companies, political bodies, community groups, government ministries, universities, school boards, and more who have negotiated and signed binding agreements with the MNO in the 31 years since its incorporation – agreements that transfer millions of dollars of taxpayer and industry money to the MNO each year.

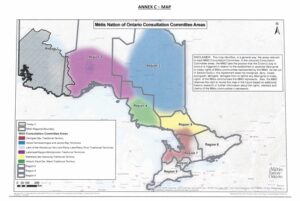

Critics of the MNO have raised two issues. First, critics have produced mountains of evidence, corroborated over the years by the MNO itself, that a large percentage of so-called “citizens” of the MNO are neither Métis nor Indigenous; and yet the MNO distributes funding and rights meant for Métis people to their non-Indigenous members. Second, the MNO claims that there are six historic Métis communities in Ontario and that MNO members who live in those areas have the right to be consulted over developments in them, critics say that those communities never existed.

Anishinabek Nation Lake Huron Regional Chief Scott McLeod, a key leader in the recent successful resistance to a federal bill that would have recognized the MNO as a government, said that in 2004, Ontario First Nations and the MNO signed an agreement promising to respect each others’ rights and aspirations, “little did we know that those aspirations were to occupy our territories!”

Sam Restoule, who works on the issue for Chiefs of Ontario, said that the 2004 protocol required annual meetings, which never did happen. In 2010, the Chiefs of Ontario rescinded the agreement. Regional Chief McLeod recalled: “There was a lag period before communities started to take notice. At first, [MNO statements and actions] were looked on with an eye roll, they were wannabees, an annoyance. That grew into a realization they weren’t going anywhere, and they were only getting stronger politically. Then we started to worry about what was happening in our Nations, saying, ‘What’s going on here? They’re shrinking our pie of Crown obligations.’ Then we asked where did they come from? Why aren’t they in our history?”

That’s when Ontario First Nations started organizing in earnest. Sam Restoule said that in 2011, the Chiefs of Ontario passed a resolution that government and industry should not consult the MNO on energy projects or resource revenue sharing.

The Chiefs of Ontario resolution didn’t dissuade the MNO from pursuing diplomatic agreements, memorandum of understanding, and impact benefit agreements with governments, educational institutions, and industry, notably including mining, nuclear waste storage, and power generation.

According to the MNO website, Ontario and the MNO signed a “Harvesting Agreement” in 2014 that identified 12 MNO harvesting areas in the province. Those areas completely overlap existing First Nation hunting territories, but those First Nations were not involved in the agreement. Under the terms of the “Harvesting Agreement”, Ontario gave the MNO authority to issue 1,250 “Harvester Cards” to be distributed at their own discretion. In 2017, Ontario lifted the cap on the number of Harvester Cards.

Notably, Canada has always decided which Indigenous people have the right to hunt through the Indian Act, so the MNO’s achievement of self-determination in this area was historically unprecedented and gave its members much more robust Indigenous hunting rights than were then or are now possessed by any other Indigenous groups in Canada.

In the following years, Ontario tasked the MNO with determining geographic areas where members of their organization had rights in Ontario. The MNO hired private research companies to look into the matter and based on their findings, asserted that there were six “historic Métis communities” in Ontario. The six new communities’ territories again overlapped with existing Ontario First Nations’ land. Ontario officially recognized those Métis communities in 2017.

Not a single Ontario First Nation, not even those whose territory were directly affected, was involved in the research or negotiations that led to the 2017 recognition of the six Ontario Métis communities. In the past few years, the methodology and conclusions of those historical research companies have been called into question by peer reviews initiated, paid for and provided to federal and provincial governments by Ontario First Nations.

Political recognition of specific Métis geographic areas gave the MNO plausible standing to fulfill reconciliation era consultation requirements for mining, nuclear waste, and power development projects. In 2015, the MNO negotiated a “Consultation Agreement” with the federal government that affirmed that industry’s obligation to consult was triggered by projects in the “area” of any of the Ontario Métis community councils when, Métis rights could be affected, even when the traditional territory of already existing First Nations lay in those areas.

In 2012, Detour Gold signed an impact benefit agreement with the James Bay-Abitibi/Temiscamingue Métis councils. According to the MNO website: “The IBA includes provisions on how the Métis community will benefit… including employment and business opportunities, training and education initiatives and financial participation in the project. The IBA also establishes a Métis scholarship and bursary program at College Boréal and Northern College.”

2014 saw the Georgian Bay Métis Community Council sign a Memorandum of Understanding with Ontario Power Generation that laid out protocols for consultations to discuss the possibility of burying nuclear waste at the south end of the Bruce Peninsula. Though no impact benefit agreement was signed, in 2022, the Georgian Bay Métis Council hosted a public event and invited the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (an organization founded by OPG), to “showcase their work in nuclear waste disposal in the area.” In 2023, Saugeen and Chippewa of the Nawash Unceded First Nations, on whose traditional territory the toxic waste may be buried, wrote a joint letter urging organizations to only negotiate with legal rights holders.

“We are troubled that organizations, proponents and governments are engaging with MNO… to arrange events regarding alleged Métis rights and activities occurring on [our] Territory.”

The MNO consulted with IAMGOLD over the Côté Gold project and signed an impact benefit agreement in 2021. Proceeds from the agreement will support the Abitibi Inland Métis, one of the six (6) asserted Ontario Métis communities.

Impact benefit agreements often yield millions of dollars for affected communities, but the MNO was also educational relationships that would help them share the history of the six new Métis communities with all Ontario residents. According to the Métis Nation of Ontario website, the organization has partnerships with the University of Ottawa, Lakehead University, the Ontario College of Art and Design, and Queen’s University among others. They provide scholarships and bursaries at many others. They offer fully-funded summer camps to train their own members in Ontario Métis culture and history.

Due to sustained pressure from First Nations, every public-school board and University in Ontario is required to seek guidance from an Indigenous Education Council. The MNO encourages their members to seek positions on these councils and provides a handbook of “best practices” for those who do. The handbook provides sample conversations that MNO reps can initiate in their local Indigenous Education Council and multiple follow-up scripts depending on the committee members’ response. Sample questions include: Does your institution teach Métis history? Does your institution display Métis symbols? The handbook advises: “If they show reluctance, make a note of this and report it to Education and Training Branch staff.” All MNO educational representatives are told to fill in standardized “meeting reports” about what is said at each meeting and submit them as soon as possible after the meeting.

The extent of influence that the MNO has achieved over public and private institutions in Ontario cannot be overstated and yet there is no hiding from the reality that First Nations across Ontario, the Chiefs of Ontario, the Manitoba Métis Federation, and the Saskatchewan Métis Federation, have said that the Métis Nation of Ontario does not have the right to negotiate on behalf of Métis people who live in Ontario.

This situation was built by governments, schools, and industry who refused to do the slow, dull work of reading and assessing the long, detailed, but easy-to-understand, historical reports that make the case for the existence of historic Métis communities in Ontario, and those that make the opposite case.

Government officials have taken the position that it would be “colonial” for them to assume the authority of determining who is Indigenous and who is not. Newly minted Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Gary Anandasangaree has been especially firm on this point, explaining: “Make no mistake, the role of the Canadian government is not to be the arbiter of Indigenous identity.” A misleading bit of word play that hides the fact that the federal government assumes the authority to determine who is Indigenous every time they decide who they will negotiate with, and who they will receive the money and rights Indigenous Nations negotiated for themselves in treaties. Imagine if a customer told the Royal Bank that they would only be paying half of their mortgage payments going forward because they’d gotten a letter from Toronto Dominion saying that they are now part of the RBC and were owed the other half? RBC would laugh at the audacity, then call a collection agency.

Distasteful as Minister Anandasangaree and other non-Indigenous leaders find it, ensuring that they are not being taken in by false claims is the work of reconciliation, and to refuse it, in this case to continue with the existing Métis Nation of Ontario partnerships without reviewing the evidence is to suggest that First Nations in Ontario lack the maturity or understanding to speak on their own behalf about their own history. A shocking position for any Ontario corporation, educational body, government ministry or municipality to take, and yet at the moment a silent and devastating consensus.

Catherine Murton Stoehr holds a Ph.D. in Canadian History specializing in treaties and diplomacy between the British and First Nations from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. A regular contributor to the Anishinabek News, she received the 2021 Debwewin Citation for excellence in journalism for her coverage of the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation.

Catherine Murton Stoehr holds a Ph.D. in Canadian History specializing in treaties and diplomacy between the British and First Nations from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. A regular contributor to the Anishinabek News, she received the 2021 Debwewin Citation for excellence in journalism for her coverage of the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation.