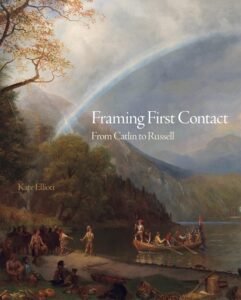

Book review: Framing First Contact: From Catlin to Russell

Framing First Contact: From Catlin to Russell by Kate Elliot represents an exploration of American artists’ attempts to represent European and Indigenous peoples’ first meetings. By situating painters and their works within U.S. history and politics, Elliot offers a marvellous explanation of what was being expressed through art. Thankfully, the book contains colour images of the paintings being discussed, which allows the reader to follow Elliot’s arguments and examples, as well as judge her perspective.

Elliot offers a very thoughtful argument that artists, in creating historically-based paintings in the 19th and early 20th centuries sought to answer concerns of a new nation, a disappearing wilderness, and a vanishing people, as well as address reconstruction and offer narratives linking modernity with an allegorical past. For instance, according to Elliot, Catlin’s series of works on LaSalle reflected a ‘pure’ West immediately before it was spoiled by contact (41-63). While Wier’s representations of Henry Hudson’s ‘discovery’ of the Hudson River were tied to self-promotion, they prove his ability to undertake epic works, appeal to his patron, and offer imagery that presented a justification for the Jacksonian Indian policy of removal (17-41). Likewise, artists such as Bierstadt and Moran, Elliot claims, carefully created works that sought to speak to a common American experience and shared history – exploration, settlement, and civilizing the continent – in an effort to paint out the divisions created by the Civil War and Reconstruction (64-96).

Finally, artists also sought to utilize the contact and exploration metaphor to emphasize the start of their respective state’s history (97-121). Taken together, these works from the 1830s to the 1910s illustrate that the artists and their works represented concerns of their respective eras, while they attempted to create a vision of America that would inspire and speak to its future and its people. Indigenous people within the paintings were meant as metaphor and colour as well as foils for images of progress and civilization as exemplified by explorers and fur traders. Elliot’s work ends on an optimistic note. She is hopeful that her discussion of artists from Catlin to Russell will “allow [us] to see productive ways that we might engage seemingly benign historical images. They say something about who we were, or who we wanted to be, but they do not define who we might become.”(124).

Overall, this is an interesting discussion of how the idea of ‘first contact’ reflected the fears, hopes, and understandings of the men and eras that created them. Similar historical paintings of contact form part of the Canadian-Settler narrative, such as Marc-Aurèle de Foy Suzor-Coté’s Jacques Cartier Meeting the Indians at Stadacona painted in 1907. Elliot’s work helps us understand Canadian artists fascination with first contact, something Kent Monkman is reinterpreting in the 21st century.

In terms of recommendations, I would highly suggest that readers use Elliot’s Framing First Contact to help situate both Canadian and American artist renderings of contact. The book will help draw the reader into understanding not what Indigenous people experienced, but what Settlers wanted us to think of themselves, their dreams, and their visions for society. Framing First Contact is aimed at a general audience but is most likely suitable for senior highschool or later readers with an interest in art and art history, as well as an interest in understanding the other – that being the Euro-Settler.

Kate Elliot, Framing First Contact: From Catlin to Russell. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2020.

ISBN: 0806167114