Nipissing First Nation testing traditional territory waters and the fish for PFAS

By Kelly Anne Smith

NIPISSING FIRST NATION—Area water and fish have been tested for PFAS, now Nipissing First Nation waits on the results.

Nipissing First Nation’s Environment Manager Curtis Avery is having tests conducted for PFAS (per- and poly-fluorinated alkyl substances) contamination from North Bay’s military base on Nipissing First Nation traditional territory and tributaries.

Curtis Avery is a proud member of Nipissing First Nation.

“In the governance of laws and the creation of how we regulate ourselves in the community, the Environment Department is also outside of the community. We were outside the community because we’ve documented where we are. On the Land Use and Occupancy Map, you can see our kill sites. Our fixed cultural sites are not on the little postage stamp we call the First Nation. We call this our administrative area, where we make our own laws and our own environmental management regimes. At the end of the day, we cannot totally control for these areas out here.”

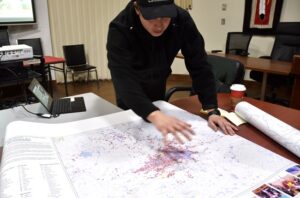

Avery waves his hand towards the outer areas on the map.

“The postage stamp that we exist on, we can do laws there, but we have other areas outside of our postage stamp that we have to care for. We share the land with North Bay. We share the land with West Nipissing, even other municipalities. We share the land with other First Nations. So, when we do a lot of research, we’re trying to identify the contamination, which is not necessarily within our lands itself but because we all share these lands. And as part of due diligence, the Environment Department does have to actively investigate these things.”

Curtis is pointing to the map.

“You can see our fish kill sites. You can see where they are. And you can see some of these areas where the moose were killed and where people stayed overnight and shot partridge. All these different areas are impacted differently by different industries,” he explains. “Here in North Bay, one of the big issues is with PFAS. PFAS started at the North Bay airport. Look at how many values are there…before the airport was there, my grandfather Garnet Avery and his family used to live on Lees Creek. They used to harvest brook trout out of that creek. The hunting, the areas where they trapped, it was all part of their use. And now, we’re losing part of the use of our Treaty lands. I know, people like to call them Crown lands, those are Treaty lands. We are all Treaty people. We share these lands.”

Avery says land users, historical contamination, and damage to the land prevents the areas from being used again. Alienation mapping needs to be undertaken he adds, of places where people can no longer go.

“This use and occupancy map is a way of us identifying what areas are important to look at. Clearly, we’re all over the place. We eat a lot of the fish from everywhere, and a lot of the land animals. Contamination is an issue regardless if we are on the First Nation.”

Avery explains that the Environment Department is working with Toronto Metropolitan University in the First Nations Environmental Contaminants Program (FNECP) for communities and organizations south of the 60th parallel. There is $97,000 to carry out the PFAS research project.

“We applied to this funding to examine the levels of PFAS. Toronto Metropolitan University has one of the best machines to analyze PFAS. Do we have an issue?” asks Curtis, pondering the PFAS Study Outline Map and pointing to all the subwatersheds that could be affected; moving to a projected slide, he explains PFAS as a group of thousands of human-made chemicals. “They look like this carbon chain here. This is PFOS, perfluorooctane sulfonate, which is actually banned. Same with PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid). You can notice there are eight carbons…they’re toxic, that bioaccumulate PFAS such as PFOS and PFOA in the systems. And they’re there forever, they’re called forever chemicals.”

The NFN Environment Manager says everyone is grappling with how to treat waters that are contaminated.

“How do we destroy this chemical? They are in the system. They’re persistent and they are finding these things as far away as the Arctic. In the air. In the rain. They’re widespread, which is scary. Unfortunately, while we banned those chemicals, they’ve regrettably substituted with something we have to find out more about. Probably, we’re finding out, it reacts the same.”

“We have to figure out how to deal with this. We can point fingers all we want. We can say we didn’t know. The fact is we have to live with this,” says Avery. “Let’s cooperate, learn more about the problem and hopefully create a solution we can use elsewhere. This is not just in North Bay. This is a huge issue in militarized landscapes…We don’t know enough about the widespread systematic contamination, even within our own region…Hence, why we’re trying to do that. Nipissing also has militarized landscapes within our postage stamp. We have a radar base here that was the pilot for all the other radar bases. And if you look at the lakes, those radar bases are contaminated.”

Avery says firefighting foam containing PFOA was used at the airforce base and contaminated the groundwater and went to Lees Creek, which empties into Trout Lake’s Delaney Bay where the intake for North Bay’s water is situated.

“There are signs you can’t even eat the brook trout there. Gets into Trout Lake. What else do we not know? It’s very interesting that Lee’s Creek is contaminated. When you look at other tributaries in the area, where do they come from?

He points to areas around the airport on the PFAS data map.

“We know these portions are contaminated. It’s actually in the Chippewa Creek watershed. Where’s the data on that? We’re not sure where that data is. That’s why we wanted to do a comprehensive investigation that would give us a perceivable baseline. What watersheds and subwatersheds are most affected?”

Avery also explains how landfills are a cause for concern.

“We have the Sand Dam dump up here in the Little Sturgeon watershed where we see lots of foam in the spring. Lot’s of foam. We’ve got some of this foam tested. It’s surfactant. It stays on top of the water. And there’s something interesting about that tributary…You know, we have our own dump here. The height of land is right next to the Leronde Creek. We want to know if there is leachate with PFAS coming into these systems.”

11 types of PFAS will be tested for and then compared to the current water quality guidelines.

“We just want to monitor our tributaries that are important to the Nipissing fisheries to make sure we’re not impacting the walleye that everybody loves.”

It’s possible that PFAS is carried from Trout Lake to end up in Lake Nipissing via the waste water treatment plant.

“That’s something we’re dealing with. We want to know, if that’s the case, what does the water look like from Jocko Point and greater North Bay area compared to outside the water treatment plant with predominant winds and flow? If you look at literature of water quality surveys, there’s a chloride bubble there from road salts and stuff. We know that things stay in this area of North Bay,” he shares. “What are the PFAS being found outside of the water treatment plant, beyond surface water? What are they in Chippewa Creek, as we slowly go up the creek? And not only that, what is coming up in Trout Lake in these other locations? And importantly, what is happening at an active plant that bakes teflon (PTFE), the IPC facility, and creates emissions to our air? When they brought that plant in, it reignited a huge issue that had been quiet for awhile.”

Avery is looking at the PFAS Study Outline map showing that the green dots represent all the sampling points.

“We need to make sound decisions based on the data. And if no one has the data, we have the due diligence ourselves to get the data. So, while we are sampling these tributaries and trying to identify some baseline, we are also looking at our fish. The fish that are being pulled out of Lake Nipissing. I already have the samples. We’re sending them off to Toronto,” he explains. “And we’re going to see, using the same sort of standard protocol that they do for contaminant sampling for mercury. I also want to see if that tissue and those livers are contaminated with PFAS. And if so, what are they? What does that look like? And that has implications to our country foods…We don’t know the results yet. That could open the door to a lot of other studies and an eye-opening issue that might grip a lot of people saying we need to do something here. This is going too far now, when you’re affecting people’s health and livelihoods. I don’t have to tell you from this map how important Lake Nipissing is to the Nipissing people.”

“This part of the study is also looking at fish being consumed by members, trying to find data on how they are consuming the fish and the basic level of concern. And what connections can we draw. They are not going to be hard connections because we would have to do a qualitative harvest survey, which we plan on doing, because we co-manage this fishery, to start understanding. We are also looking at some game species too. We’ve seen in some situations (US) deer and turkeys contaminated with PFAS,” he continues. “We’re investigating those levels. We’re looking at our food, the fish and we’re trying to do community engagement. And we’re working with Metropolitan University to try and understand how we make this a program and rebuild capacity to keep this study after this funding and this report is done. How do we keep monitoring it?”