Nipissing First Nation citizen publishes new book

By Kelly Anne Smith

NIPISSING FIRST NATION — Les Couchi was quite comfortable on the bench with photographer friend Pat Stack. Armed with long lenses on a sunny May morning, they patiently wait for the perfect photo. Moments before, Couchi captured the bright orange of a Baltimore Oriole in full flight plumage (though he predominantly shoots eagles).

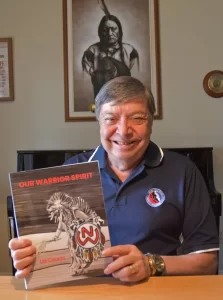

Couchi is now in the limelight with his new book, Our Warrior Spirit. It’s packed with stories on the history of Nipissing First Nation.

After listening to the youth during the Robinson Huron Treaty discussions, Couchi decided a resource was needed for educating the youth and those who did not know the true history of Nipissing First Nation and its members.

“There was a lot of discussion in the community about young people wanting the same as older people. And I thought, they are missing something here. They’re missing the methodology in doing it that way and the message in doing it that way. To break it down, if you’re twenty years old and you’re getting the same as someone who is seventy — a seventy-year-old has missed seventy payments— you’ve only missed twenty, for one thing, but you’ve also missed out on all the hardships,” he explains. “There’s obviously a dramatic shift in Nipissing First Nation. I’m sure it’s replicated in other First Nations. This is something they miss. The story of hardship, recovery, and going forward, what-ifs. Where’s our future? That’s basically what my intent was.”

Couchi previously wrote stories for the community on the Facebook page, whether it was about digging holes or what trails meant to Nipissing First Nation.

“There used to be pathways everywhere on the First Nation, but they are no more.”

In November, Les told his wife, Mary Lou McKeen, that he was going to write the book. Soon, she and her sister Pearl became his writing team. Les says numerous people also helped write the new book with their stories and consultations.

Our Warrior Spirit is dedicated to June Goulais Commanda. Les tells her story, as does June, of being an Indian Residential School Survivor. Many more historical glimpses of the lives of talented and resilient First Nation people are told. Les says he gives a lot of explanations.

“In the first part, I talk of how this all came to be. Residential schools, Indian affairs, all of those roles that were [imposed on] us; how they took us down and tried to destroy us. They tried to destroy us, but it didn’t work.”

Couchi calls colonialism a practice of domination.

“A friend of mine had this certificate where someone got married and they were deIndianed.”

He points out a blue card given to Velma Doreen Murray as a certificate of enfranchisement, deeming her not to be an Indian any longer after marriage. There is a photo of a beige card from an Indian agent giving permission to leave the reserve for hunting purposes.

“Young people don’t know about this stuff. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be saying we want an equal share. I think if they would have known more, they would not have gone there.”

Les recounts the growth of hockey in Nipissing First Nation and how the game positively influenced the community.

“Without question, hockey was a pivotal unifying force across our community beginning in the early 1950s,” he says. “In the fifties and the forties, we didn’t have money for cars, and when your reserve is 23 miles long (37 km), for people at this end, you might as well be 200 miles away at the other end because we never saw those people. There was some intermarriage, but still, there wasn’t a lot of visiting from your cousins and the other part of the reserve.”

“It’s kind of ironic, but at the same time, in the fifties, we built our own rink. All by ourselves, we built our own rink. Garden Village got a rink. They needed one, too. So, we started playing hockey and they started playing hockey. The talent was there. And then the Warriors come along. And the two communities take their best players from each one and they create this winning team. The winning team adds to the self-esteem of a community…We come together, and now we’re a united front,” he continues. “At the same time, the demographic would tell you that when they started educating the kids in the same classrooms as everybody else, First Nation students earned university degrees, highschool completions, and college certificates. Twenty years after that, what would you expect? More academics of higher levels coming into the community. Then human resources bring in business. And the numbers are staggering. There are 81 businesses.”

Les shows the photo of the rink they built.

“That involved going to Duchesnay with a sled and a bucket. Filling the barrel up. Pulling that thing up, because it’s a steady grade to my home on Highway 17. First, we would tap it all down and smooth it all out, then pour the water on it. It was a lot of hard work, but we did it.”

The passion for hockey shines through when Les explains his big moments.

“My achievements were ending up a Maple Leaf for a day; my jacket ended up in the Hockey Hall of Fame; and I became good friends with Johnny Bower and Ted Nolan.”

The short bios of the Warriors are great reads, as are the recollections of the achievements of the “lady Warriors.” He says they were pivotal in the success of the Warriors.

“They created the Homemakers Club. The Homemakers originally started in 1955, and they were a social safety net. Funerals would happen, they would take care of the food, flowers, what have you. Or someone would be sick and they would provide food for that person and do good things. Part of what they did was take care of the Warriors, paying for equipment, paying for hockey sticks.”

Future Opportunities such as establishing a museum to protect and preserve artifacts, knowledge, and culture of Nipissing First Nation are also highlighted. The author also calls on Nipissing First Nation to designate protected spaces of flora and fauna on traditional land.

Couchi appeals for street and school names to be changed. He calls for the renaming of Cockburn Road leading into Garden Village. Indian agent George P. Cockburn arranged a land surrender vote by bypassing the elected Chief Alexander Dokis. And he says North Bay’s St. Joseph-Scollard Hall Catholic Secondary School should have its name reevaluated as it’s named after Bishop Scollard.

Back on the bench outdoor, he listens intently as Stack talks of the bird visitors he missed, such as a hairy woodpecker and the pair of grackles performing their mating dance. Les readies his camera to capture another superior avian image.

Our Warrior Spirit was printed in Canada and is available on Amazon.