Justice Myers finds $510 million payout ‘was not the deal’

By Catherine Murton Stoehr

By Catherine Murton Stoehr

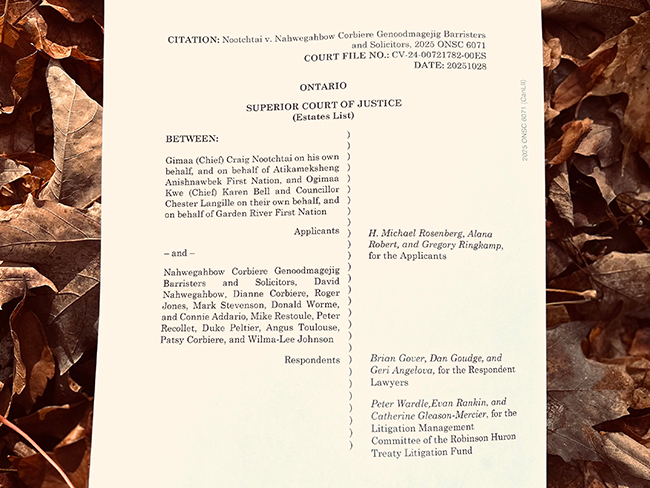

How can a non-Indigenous judge tell Anishinabek people that they are not allowed to pay their Anishinabek lawyers the money they want to pay them, and that they believe a Pipe Ceremony has honour bound them to pay? In his 63-page judgement reviewing the fees claimed by the Legal Team of Nahwegahbow Corbiere for their work in the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Ontario Superior Court Justice Fred Myers suggests that neither Canadian or Anishinabek law left him any alternative.

Justice Myers has ordered that the Legal Team, who were paid $17 million before the settlement amount of $10 billion was determined, should be paid an additional $23 million for a total of around $40 million in recognition of the Legal Team’s “great legal work” representing their clients “zealously, resolutely, passionately and with extraordinary success.”

The Judge has ordered Nahwegahbow Corbiere to refund $232 million of the fees they have been paid to the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Fund (hereafter “The Fund”) and ordered the Fund to treat a $255 million gift it has received from the Legal Team as “regular settlement proceeds.”

In his judgement Justice Myers noted that he asked the lawyer for the Litigation Trust why the Trust itself supported the legal team in its claim to be owed $510 million “when the Trustees owe fiduciary duties to the 40 000 members who stand to gain from the Legal Team being held to fair and reasonable fees”? Myers observed that Trust members “seem to think that the deal is that the lawyers get 5% and that they are duty and honour bound to implement that deal. “But,” Myers asserts, “that was not the deal.”

The partial contingency agreement signed by the Legal Team back in 2011 stated that the agreement itself was “subject to… the Solicitors Act and the usual controls and protections available at law.” Having the fee reviewed by a judge is one of those usual protections. Judges regularly reduce legal fees from the amount claimed by lawyers for various reasons, as Myers has done in this case.

Justice Myers related that Elder testimony in the fee assessment hearing suggested that “the idea of a bilateral commercial contract in which people bind themselves by law to specific conduct is unknown to Anishinaabe law and tradition.” Elder Margaret Toulouse testified that “Sharing is a fundamental teaching to respect creation. It means that we only take what we need. She explained that anyone who over-harvests depletes future growth.”

Two Elders expressed the primary importance of covenant keeping to Anishinaabe values and expressed gratitude to the Legal Team of Nahwegahbow Corbiere for giving the Robinson Huron Fund a gift of $255 million out of their fees.

Justice Myers observed “Neither elder … discussed how paying $255 million to six people is consistent with obligations that are always defined to some degree by considering relative need in Anishinaabe law and tradition.”

The judge was troubled that in the $255 million gift offered to the Fund by the Legal Team, “…one of the uses is to pay the Legal Team’s fees for the ongoing piece of the Restoule litigation… the legal team apparently does not see the self-interested nature of their offer to make that decision for the Fund to benefit themselves.”

Even as the law firm and members of the Litigation Trust worked to be guided by Anishinabek law ambiguities arose over how that should be done. In a negotiation over the exact percentage to be paid to the lawyers three years into the project the Robinson Huron Trustees believed that the commitments they made to the Legal Team at the Pipe Ceremony meant they could not sever the partnership and so they had no choice but to come to an agreement, the Legal Team, who possibly had a different interpretation of the Pipe Ceremony obligations, threatened to quit over the percentage issue.

Under Canadian law Justice Myers found that the partial contingency agreement was compromised because the Legal Team failed to give the Litigation Trust members sound counsel when the Legal Team’s own financial interests were at stake, noting that this wasn’t done “in bad faith”, it’s just human nature.

Justice Myers noted that “the Legal Team did not suggest or insist that the Fund or the Chiefs obtain independent legal advice” when negotiating the initial fee agreement.

The Legal Team did not advise the Trustees that there were multiple ways that they could ensure the best interests of the Robinson Huron First Nations in the fee agreement. They could set a cap on the total fee, regardless of percentage, they could have required the law firm to take on a part or all of the out-of-pocket expenses of the trial and take on or share the risk of the bank loan if needed. In 2014 the First Nations’ future gaming revenues were used to secure a bank loan to support the case.

In all this Myers found that there was no evidence that the lawyers told the trustees that “lawyers funding disbursements and costs were normal incidents of a contingency fee agreement” or that the legal team tested the First Nations’ financial wherewithal to withstand the 81 per cent of the litigation cost burden that was coming their way under this agreement.”

Once the $10 Billion settlement was announced the Litigation Fund Managers met with the Chiefs of the 21 First Nations twice, discussing the legal fees at both meetings. At both meetings Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Gimaa Craig Nootchtai and Garden River Gimaa Andy Rickard, now succeeded by Chief Karen Bell, strongly urged that fees should be carefully reviewed before payment.

Myers decision relates that at those meetings “Ms. Corbiere twice gave advice to her clients that was simply incorrect expressly to pressure them to recognize her fees without obtaining independent legal advice…. She created false urgency to imperil the Funds’ and the Chiefs’ obvious priority to distribute the settlement funds. Ms. Corbiere implored her clients as “family” invoking the pipe ceremony to play on their honour without ensuring they understood that assessing legal fees is both honourable under the applicable Ontario law and is expressly preserved in the contingency fee structure.”

According to Justice Myers Mr. Nahwegahbow “told the Trustees and Chiefs that their right to assess fees was lost because of the existence of the contingency agreement.”

The second meeting voted down Chief Nootchtai’s proposal to seek independent legal advice and 11 days later $255 million dollars was paid to the legal team.

Having determined that the contingency agreement itself was not fair and that neither a $510 million nor a $255 million legal fee is reasonable Justice Myers used existing precedents to come to the $40 million figure.

Multiple factors affect the size of the premium that a lawyer can charge, and Myers was adamant that Nahwegahbow Corbiere’s work was of the highest quality throughout. However, Myers found that the massive size of the award made a calculation based on percentage unreasonable and that the extent to which Nahwegahbow Corbiere limited their own financial risk in the case meant that only 5.78 million of their fees total was liable to benefit from a contingency premium.

The lawyers who worked on the Jordan’s Principle case Moushoom v Canada secured a $23 billion award for their clients, the largest award in Canadian Legal history. They had their $100 million fee reduced to $40 million by a legal review. Myers noted that his determination that Nahewegahbow Corbiere should likewise be given a total fee of $40 million, equal to the fee paid in Moushoom, and double their actual billable fees “is a spectacular outcome [for the lawyers] unless one is comparing it to an utterly unrealistic claim.”

Lawyers in R. v Imperial Tobacco, a 2025 class action in Quebec were paid $900 million. The judge who determined that amount noted that the legal fee did not reduce payments to the beneficiaries, that the lawyers worked with no pay for 26 years and bore 100 per cent of the out-of-pocket costs of the litigation. The $900 million represented a four-fold increase in the total amount of money they risked. Nahwegahbow Corbiere are seeking a payment equal to 88 times the value of the funds they risked during the course of the Restoule case despite the “risk undertaken by the Legal Team” being “at the lowest end of risk in mega-fund cases.”

“In a video statement posted on YouTube after Myers’ decision was released, Mike Restoule of Nipissing First Nation, who chairs the Litigation Fund, said community members “are acting in colonial ways” because of the settlement and specifically because of “the recent decision of the Judge in the legal fees assessment case.” Restoule said “That is not our way. Since the beginning of time our ways have always been to take care of each other. Each individual as one to contribute to the overall strength of our nation.”