‘God and the Indian’ an angry and healing play

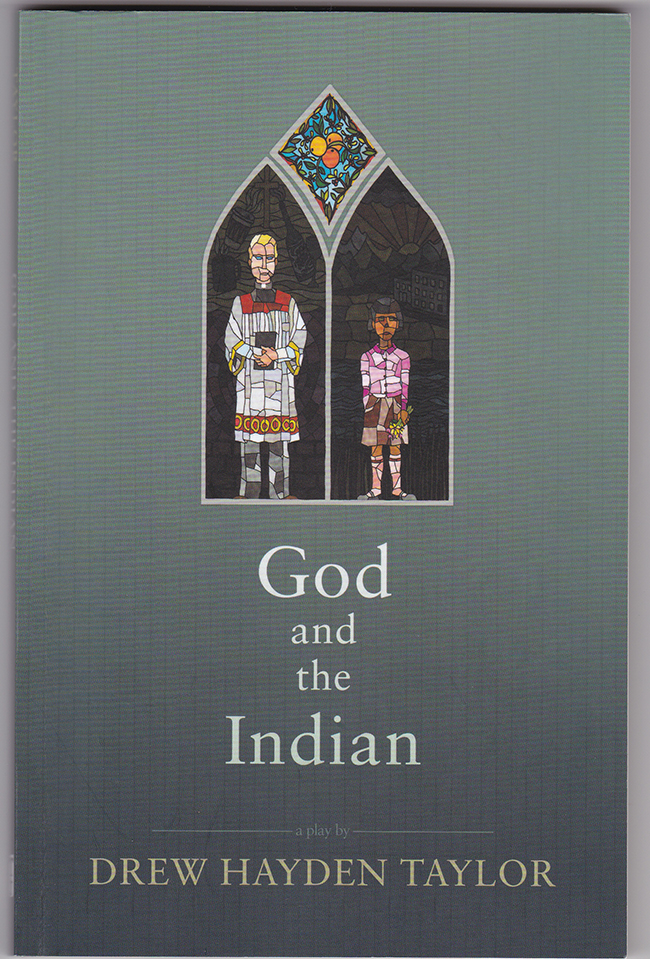

Drew Hayden Taylor’s God and the Indian: A Play

The playwright ends his Preface to the published script: “This is an angry play. This is a healing play” (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2014, p. x). First produced in Vancouver in 2014, God and the Indian seems neither, but rather, as one of the two characters often hints at, a ghost story. Johnny, a Cree woman—seriously ill and a homeless survivor of a residential school–confronts George, a newly promoted assistant Anglican bishop and her former teacher at St. David’s Anglican residential school. She is in her early 50s, he his mid 60s, and the time setting is early 2000s somewhere in Canada, with the play’s action having taken place forty years earlier.

The pair relives those early days over two acts that are, by turns, moving, disturbing, and funny. Ojibway writer Taylor’s creation of the figure of Johnny recalls the many engaging comedies he has written about wise and hopeful contemporary aboriginals who make audiences laugh (for example, The Bootlegger Blues).

While Johnny is warm and engaging, though claiming to be already dead from so much abuse, powerlessness, and sadness in her life, Rev. George Linus King is in fact a much more perplexing figure in his apparent stiffness and coldness. Johnny’s aim as she follows Rev. George to his office and breaks in is to make him remember and admit to abusing her and, as she later states, to feel pain in doing so. The problem with George is that he seems to feel little. We glimpse his heart fully only at play’s end.

George voices what must seem to Johnny and perhaps the audience as well to be glib sentiments: “God works in mysterious ways” (p. 36); Johnny’s not “dealing with” her issues (p. 64); “you can have a future” (p. 54); and, “I’m here to . . . make the world a better place” (p. 17). As Johnny lays bare the painful details of her own personal past, George speaks in generalities about, for example, having been present at the reading of the Anglican Church’s official apology to residential school survivors, from which George quotes. His own family, shown in a photo–wife and three children—remain somehow the most sensitive topic Johnny raises, one that arouses the only genuine feelings of protectiveness in the priest.

That the woman and man cannot communicate, as though speaking different languages, is made obvious from the start when Johnny enters George’s office and declares in Cree, “Nintoogeewaan . (I want to go home” (p. 3). His reply, “I’m sorry. What did you say?”, predicts the failures to understand that create this play’s effective dramatic tension. Are the failures unavoidable, or are they willed? Johnny does not accept George’s claims of not knowing her; George will not acknowledge her accusations of abuse.

Elements of doubt and questions of faith intervene to complicate the drama. Johnny’s years of drinking have clouded her memory. George, who gradually reveals that other accusations surfaced against other priests at St. David’s, maintains his innocence of all wrongdoing at the school except, “I confess I heard about things that happened there . . . [and] I didn’t do anything to stop it” (p. 40). The only faith remaining to Johnny is that she be recognized and in that way somehow given back a part of her life. George’s faith apparently remains in his being “a nice guy” (p. 49) at this point in his life, regardless of past failings.

The God of the work’s title seems conspicuously absent in both characters’ lives, despite the painting of Jesus with children, hanging behind the priest’s desk, to whom he speaks at play’s opening. Johnny retains her mother tongue and having been named after her beloved grandmother as well as stories of life before, at age six, having been taken to St. David’s. But of Christianity she says, “I don’t think God likes Indians” (p. 58). Almost as troubling as the question of George’s being guilty or not of sexual abuse is whether or not he believes in God, or what kind of God he believes in. For he shows much more fear of Johnny than compassion for her. She is destitute, and he is surrounded by the trappings of material success.

Johnny is a ghost because nobody acknowledges her. But a part of George too seems long dead. At the play’s remarkably affecting ending, George hints at a confession, and only after that does he seem to speak to Johnny from his heart, recalling her real name—Lucy. She laughs painfully and replies, “It’s always nice to be remembered. . . . But I know that you’ve lied. . . . To God. To yourself” (p. 79). As she is about to leave his office, he speaks haltingly to her: “Ka . . . Ka . . . Ka-wapamitin . . . Lucy” (p. 80; ellipsis in original). Again she laughs, replying, “Lucy’s dead.”

Audiences are left with a clash of spirit worlds in this ghost story, both characters apparently haunted rather than consoled by their beliefs. Johnny exits, and a weapon that appears earlier in the play is seen to have mysteriously disappeared as though by the hand of an unseen spirit. As George, alone, looks towards Jesus, “the sound of children’s voices and the hymn [that he hummed at the start] echo in his memory” (p. 80). The power of Taylor’s play seems to lie in the realization that to have true faith, we need a true story of ourselves and our past.

In May of this year, God and the Indian played at Toronto’s Aki Theatre and later at the Firehall Arts Centre in Vancouver.

Shannon Hengen is a writer based in Sudbury, Ontario.